Lens (vertebrate anatomy)

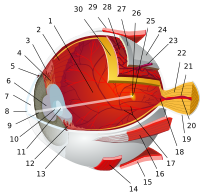

In many land animals the shape of the lens can be altered, effectively changing the focal length of the eye, enabling them to focus on objects at various distances.

Accommodation in humans is well studied and allows artificial means of supplementing our focus, such as glasses, for correction of sight as we age.

In a human adult, the lens is typically about 10mm in diameter and 4mm thick, though its shape changes with accommodation and its size grows throughout a person's lifetime.

[6] The capsule is very elastic and so allows the lens to assume a more spherical shape when the tension of the suspensory ligaments is reduced.

The human capsule varies from 2 to 28 micrometres in thickness, being thickest near the equator (peri-equatorial region) and generally thinner near the posterior pole.

The lens fiber cytoplasms are linked together via gap junctions, intercellular bridges and interdigitations of the cells that resemble "ball and socket" forms.

With the advent of other ways of looking at cellular structures of lenses while still in the living animal it became apparent that regions of fiber cells, at least at the lens anterior, contain large voids and vacuoles.

The first stage of lens formation takes place when a sphere of cells formed by budding of the inner embryo layers comes close to the embyro's outer skin.

The sphere of cells induces nearby outer skin to start changing into the lens placode.

[4] Several proteins control the embryonic development of the lens though PAX6 is considered the master regulator gene of this organ.

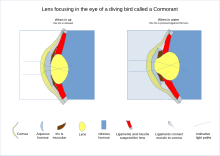

[21] In many aquatic vertebrates, the lens is considerably thicker, almost spherical resulting in increased light refraction.

[24][25] Even among terrestrial animals the lens of primates such as humans is unusually flat going some way to explain why our vision, unlike diving birds, is particularly blurry under water.

[26] In humans the widely quoted Helmholtz mechanism of focusing, also called accommodation, is often referred to as a "model".

Normally the lens is held under tension by its suspending ligaments being pulled tight by the pressure of the eyeball.

At short focal distance the ciliary muscle contracts relieving some of the tension on the ligaments, allowing the lens to elastically round up a bit, increasing refractive power.

While not referenced this presumably allows the pressure in the eyeball to again expand it outwards, pulling harder on the lens making it less curved and thinner, so increasing the focal distance.

[33] The theory allows mathematical modeling to more accurately reflect the way the lens focuses while also taking into account the complexities in the suspensory ligaments and the presence of radial as well as circular muscles in the ciliary body.

In a 1911 Nobel lecture Allvar Gullstrand spoke on "How I found the intracapsular mechanism of accommodation" and this aspect of lens focusing continues to be investigated.

Since that time it has become clear the lens is not a simple muscle stimulated by a nerve so the 1909 Helmholtz model took precedence.

[45][46][47] Magnetic resonance imaging confirms a layering in the lens that may allow for different refractive plans within it.

These pads compress and release the lens to modify its shape while focusing on objects at different distances; the suspensory ligaments usually perform this function in mammals.

[26] In cartilaginous fish, the suspensory ligaments are replaced by a membrane, including a small muscle at the underside of the lens.

In teleosts, by contrast, a muscle projects from a vascular structure in the floor of the eye, called the falciform process, and serves to pull the lens backwards from the relaxed position to focus on distant objects.

While amphibians move the lens forward, as do cartilaginous fish, the muscles involved are not similar in either type of animal.

There is no aqueous humor in these fish, and the vitreous body simply presses the lens against the surface of the cornea.

It is the way optical requirements are met using different cell types and structural mechanisms that varies among animals.

β and γ crystallins are found primarily in the lens, while subunits of α -crystallin have been isolated from other parts of the eye and the body.

[60] The chaperone functions of α-crystallin may also help maintain the lens proteins, which must last a human for their entire lifetime.

[64] People lacking a lens (a condition known as aphakia) perceive ultraviolet light as whitish blue or whitish-violet.

[67] By nine weeks into human development, the lens is surrounded and nourished by a net of vessels, the tunica vasculosa lentis, which is derived from the hyaloid artery.