Accommodation (vertebrate eye)

Accommodation is the process by which the vertebrate eye changes optical power to maintain a clear image or focus on an object as its distance varies.

As a result, animals living in air have most of the bending of light achieved at the air/cornea interface with the lens being involved in finer focus of the image.

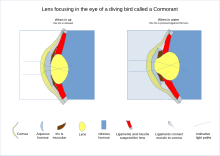

Generally mammals, birds and reptiles living in air vary their eyes' optical power by subtly and precisely changing the shape of the elastic lens using the ciliary body.

The small difference in refractive index between water and the hydrated cornea means fish and amphibians need to bend the light more using the internal structures of the eye.

[1] Varying forms of direct experimental proof outlined in this article show that most non-aquatic vertebrates achieve focus, at least in part, by changing the shapes of their lenses.

[2] Others such as Hermann von Helmholtz and Thomas Henry Huxley refined the model in the mid-1800s explaining how the ciliary muscle contracts rounding the lens to focus near.

Normally the lens is held under tension by its suspending ligaments and capsule being pulled tight by the pressure of the eyeball.

This is achieved by relaxing some of the sphincter-like ciliary muscles allowing the ciliarly body to spring back, pulling harder on the lens making it less curved and thinner, so increasing the focal distance.

[7] The theory allows mathematical modeling to more accurately reflect the way the lens focuses while also taking into account the complexities in the suspensory ligaments and the presence of radial as well as circular muscles in the ciliary body.

While this concept may be involved in the focusing it has been shown by Scheimpflug photography that the rear of the lens also changes shape in the living eye.

In a 1911 Nobel lecture Allvar Gullstrand spoke on "How I found the intracapsular mechanism of accommodation" and this aspect of lens focusing continues to be investigated.

By the fifth decade of life the accommodative amplitude can decline so that the near point of the eye is more remote than the reading distance.

[31] The amplitude of accommodation is a clinical measurement that describes the maximum potential increase in optical power that an eye can achieve in adjusting its focus.

However, Hofstetter's work was based on data from two early surveys[38][39] which, although widely cited, used methodology with considerable inherent error.

(Donders, Sheard, Duane, Turner for reference) When humans accommodate to a near object, they also converge their eyes and constrict their pupils.

[47] While it is well understood that proper convergence is necessary to prevent diplopia, the functional role of the pupillary constriction remains less clear.

[50] Premature sclerosis of lens or ciliary muscle weaknesses due to systemic or local cases may cause accommodative insufficiency.

[52] Aquatic animals include some that also thrive in the air so focusing mechanisms vary more than in those that are only land based.

Some whales and seals are able to focus above and below water having two areas of retina with high numbers of rods and cones[53] rather than one as in humans.

These pads compress and release the lens to modify its shape while focusing on objects at different distances; the suspensory ligaments usually perform this function in mammals.

[54] In cartilaginous fish, the suspensory ligaments are replaced by a membrane, including a small muscle at the underside of the lens.

In teleosts, by contrast, a muscle projects from a vascular structure in the floor of the eye, called the falciform process, and serves to pull the lens backwards from the relaxed position to focus on distant objects.

While amphibians move the lens forward, as do cartilaginous fish, the muscles involved are not similar in either type of animal.

It is the way optical requirements are met using different cell types and structural mechanisms that varies among animals.