External morphology of Lepidoptera

Comprising over 160,000 described species, the Lepidoptera possess variations of the basic body structure which has evolved to gain advantages in adaptation and distribution.

[1] Lepidopterans undergo complete metamorphosis, going through a four-stage life cycle: egg, larva or caterpillar, pupa or chrysalis, and imago (plural: imagines) / adult.

There are two pairs of membranous wings which arise from the mesothoracic (middle) and metathoracic (third) segments; they are usually completely covered by minute scales.

In common with other members of the superorder Holometabola, Lepidoptera undergo complete metamorphosis, going through a four-stage life cycle: egg, larva / caterpillar, pupa / chrysalis, and imago (plural: imagines) / adult.

[9] Lepidopterans range in size from a few millimetres in length, such as in the case of microlepidoptera, to a wingspan of many inches, such as the Atlas moth and the world's largest butterfly Queen Alexandra's birdwing.

[14][15]: 28–40 The characteristics of immature stages are increasingly used for taxonomic purposes as they provide insights into systematics and phylogenies of Lepidoptera that are not apparent from examination of adults.

The regions of the head have been divided into a number of areas which act as a topographical guide for description by lepidopterists but cannot be discriminated in terms of their development.

[5] The ocelli of Lepidoptera are reduced externally in some families; where present, they are unfocussed, unlike stemmata of larvae which are fully focussed.

[3] There is an allometric scaling relationship between body mass of Lepidoptera and length of proboscis[22] from which an interesting adaptive departure is the unusually long-tongued sphinx moth Xanthopan morganii praedicta.

Charles Darwin predicted the existence and proboscis length of this moth before its discovery based on his knowledge of the long-spurred Madagascan star orchid Angraecum sesquipedale.

The forelegs spring from the prothorax, the forewings and middle pair of legs are borne on the mesothorax, and the hindwings and hindlegs arise from the metathorax.

[11][27] The upper and lower parts of the thorax (terga and sterna respectively) are composed of segmental and intrasegmental sclerites which display secondary sclerotisation and considerable modification in the Lepidoptera.

In more derived groups, the meso-thoracic wings are larger with more powerful musculature at their bases and more rigid vein structures on the costal edge.

[13]: 635 [32]: 56 Homoneurous moths tend to have the "jugum" form of wing coupling as opposed to the "frenulum–retinaculum" arrangement in the case of more advanced families.

The Lepidoptera have developed a wide variety of morphological wing-coupling mechanisms in the imago which render these taxa "functionally dipterous" (two winged).

[35] The more primitive groups have an enlarged lobe-like area near the basal posterior margin (i.e. at the base of the forewing) called a jugum, that folds under the hindwing during flight.

[8] A few taxa of the Trichoptera (caddisflies), which are the sister group to the Lepidoptera, have hair-like scales, but always on the wings and never on the body or other parts of the insect.

[46] In the case of the Kaiser-i-Hind (Teinopalpus imperialis), the three-dimensional photonic structure has been examined by transmission electron tomography and computer modelling to reveal naturally occurring "chiral tetrahedral repeating units packed in a triclinic lattice",[47][48] the cause of the iridescence.

Scales enable the development of vivid or indistinct patterns which help the organism protect itself by camouflage, mimicry, and warning.

The "solid" scales of basal moths are however not as efficient as those of their more advanced relatives as the presence of a lumen adds air layers and increases the insulation value.

The adults emerging from pupae are covered with soft, loose adhesive scales which rub off and stick on the ants as they make their way out of the nest after hatching.

[49] Male Lepidoptera possess special scales, called androconia (singular – androconium), which have evolved as a result of sexual selection for the purposes of disseminating pheromones for attracting suitable mates.

[13]: 644 Caterpillars of many taxa that have sequestered toxic chemicals from host plants or have sharp urticating hair or spines, display aposematic colouration and markings.

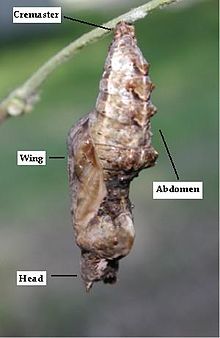

[67]: 31 A cocoon is a casing spun of silk by many moth caterpillars, and numerous other holometabolous insect larvae as a protective covering for the pupa.

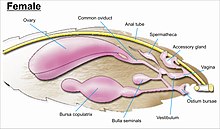

[70] Among the features discernible in the head region of a pupa are sclerites, sutures, pilifers, mandibles, eye-pieces, antennae, palpi, and the maxillae.

The pupal abdomen exhibits the ten segments, spines, setae, scars of larval prolegs and tubercles, anal, and genital openings, as well as spiracles.

[14]: 23–29 While the pupa is generally stationary and immobile, those of the primitive moth families Micropterigidae, Agathiphagidae, and Heterobathmiidae have fully functional mandibles.

All other superfamilies of the Lepidoptera are more specialised, have non-functional mandibles, appendages and body attached to the pupal skin, and lose a degree of independent movement.

In the case of a few hawk moths, such as Theretra latreillii, the wriggling of the abdomens is accompanied by a rattling or clicking sound which adds to the startle effect.

[77] The role of filamentous tails in Lycaenidae has been suggested as confusing predators as to the real location of the head, giving them a better chance of escaping alive and relatively unscathed.