Letters on Sunspots

Letters on Sunspots (Istoria e Dimostrazioni intorno alle Macchie Solari) was a pamphlet written by Galileo Galilei in 1612 and published in Rome by the Accademia dei Lincei in 1613.

[2] The Letters on Sunspots was a continuation of Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo's first work where he publicly declared that he believed that the Copernican system was correct.

[6] There were reports from Islamic[7] and European astronomers of sunspots in the early ninth century;[8][9] those occurring in 1129 were recorded by both Averroes[7] and John of Worcester, whose drawings of the phenomenon are the earliest surviving today.

[12] In 1611 Johannes Fabricius saw them, and published a pamphlet entitled De Maculis in Sole Observatis, which Galileo was not aware of before he wrote the Letters on Sunspots.

[18] Having published Scheiner's first three letters under the title Tres Epistolae de Maculis Solaribus ("Three Letters on Solar Spots"), Welser now published his second three, also in 1612, as De Maculis Solaribus et Stellis circa Iovis Errantibus Accuratior Disquisition ("A More Accurate Disquisition Concerning Solar Spots and Stars Wandering around Jupiter").

[19] Publishing the Letters on Sunspots was a major financial and intellectual venture for the Accademia dei Lincei, and it was only the fourth title it had decided to issue.

[20] Federico Cesi paid for the publication himself, and wanted to strike a careful balance between introducing extraordinary new ideas and avoiding causing offence to people who might find those views problematic.

In the case of Letters on Sunspots his critical support appears to have been helpful in ensuring that publication was not prevented by influential Dominicans of the Sacred Palace.

[30] He develops his argument to show that sunspots were not permanent and did not have a regular pattern of movement as they would if they were heavenly bodies – they were nothing like the moons of Jupiter that he had himself discovered and described in Siderius Nuncius.

[28]: 254 Lastly, he humorously compares scholars who insist that every detail of Aristotle's writing must be true, whether it corresponds with reality or not, with those artists who draw portraits of people in fruit and vegetables.

'As long as these oddities are offered as jokes, they are nice and pleasing... but if someone, perhaps because he had consumed all his studies in a similar style of painting, then wanted to draw the general conclusion that every other method of imitating was imperfect and blameworthy, surely Cigoli and other celebrated painters would laugh at him.

A large portion of the Third Letter is taken up with disproving Apelles' assertion that he had observed spots passing across the Sun at different speeds – one, on the diameter, taking sixteen days, and another, at a lower latitude, in just fourteen.

He then demonstrates that for the spots Apelles had observed to change in apparent size as they did, they would need to be on the face of the Sun, because if they were even a short distance above its surface the foreshortening effect would be remarkably different.

'[28]: 286 To dispense once and for all with Apelles' claim that the moons of Jupiter 'appear and disappear', Galileo provides predictions for their positions for the next two months to prove the regularity of their motions.

[28]: 287 To demonstrate that natural philosophy must always be led by observation and not try to fit new facts into preconceived frameworks, Galileo comments that the planet Saturn had recently and surprisingly changed its appearance.

[28]: 295 Galileo concludes his remarks by criticising those who doggedly adhere to Aristotle's views, and then, drawing together all he has said about sunspots, the moons of Jupiter, and Saturn, ends with the first explicit endorsement of Copernicus in his writings: I think it is not the act of a true philosopher to persist – if I may say so – with such obstinacy in maintaining Peripatetic conclusions that have been found to be manifestly false, believing perhaps that if Aristotle were here today he would do likewise, as if defending what is false, rather than being persuaded by the truth, were the better index of perfect judgement... [and] I say to your Lordship that this star too [i.e. Saturn] and perhaps no less than the emergence of the horned Venus, agrees in a wondrous manner with the harmony of the great Copernican system, to whose universal relations we see such favourable breezes and bright escorts directing us.

[34] In a letter to Federico Cesi, Galileo said: 'I have finally concluded, and I believe I can demonstrate necessarily, that they [i.e. the sunspots] are contiguous to the surface of the solar body, where they are continually generated and dissolved, just like clouds around the earth, and are carried around by the sun itself, which turns on itself in a lunar month with a revolution similar [in direction] to those other of the planets... which news will be I think the funeral, or rather the extremity and Last Judgement of pseudophilosophy....

[39] Scheiner argued that what appeared to be spots on the Sun were in fact clusters of small moons, thereby trying to deploy one of Galileo's own discoveries as an argument for the Aristotelian model.

I see young men.... who, although furnished.... with a decent set of brains, yet not being able to understand things written in gibberish [i.e. Latin], take it into their heads that in these crabbed folios there must be some grand hocus-pocus of logic and philosophy much too high up for them to think of jumping at.

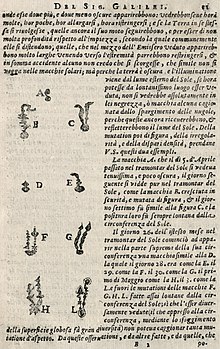

This relationship may have recommended him as one whose involvement in a publication would perhaps ease its path through censorship; in addition his craftsmanship was outstanding, and he devised a novel etching technique specially in order to make the sunspot illustrations as realistic as possible.

[58][59] In De revolutionibus orbium coelestium Copernicus had published both a theoretical description of the universe and a set of tables and calculating methods for working out the future positions of the planets.

More generally, Galileo was using his predictions to establish the validity of his ideas – if he could be demonstrably right about the complex movements of many small moons, his readers could take that as a token of his wider credibility.

From the middle of the seventeenth century the debate about whether Scheiner or Galileo was right died down, partly because the number of sunspots was drastically reduced for several decades in the Maunder Minimum, making observation harder.

[64][65] In 1619, Mario Guiducci published A Discourse on Comets, which was actually mostly written by Galileo, and which included an attack on Scheiner, although its focus was the work of another Jesuit, Orazio Grassi.

In 1611, before the Letters on Sunspots appeared, Francesco Sizzi had published Dianoia Astronomica, attacking the ideas of Galileo's earlier work, Siderius Nuncius.

Galileo was to adopt this observation and deploy it in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in 1632 to demonstrate that the Earth tilted on its axis as it orbited the Sun.

[11] In his treatise on the comet of 1618, Astronomischer Discurs von dem Cometen, so in Anno 1618, Michael Maestlin made reference to the work of Fabricius and cited sunspots as evidence of the mutability of the heavens.

[85] In Il Saggiatore (The Assayer) (1623) Galileo was mostly concerned with faults in Orazio Grassi's arguments about comets, but in the introductory section he wrote : 'How many men attacked my Letters on Sunspots, and under what disguises!

Others, not wanting to agree with my ideas, advanced ridiculous and impossible opinions against me; and some, overwhelmed and convinced by my arguments, attempted to rob me of that glory which was mine, pretending not to have seen my writings and trying to represent themselves as the original discoverers of these impressive marvels.

[27] In 1632 Galileo published Dialogo sopra i due Massimi Sistemi del Mondo (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems), a fictitious four day-long discussion about natural philosophy between the characters Salviati (who argued for Copernican ideas and was effectively a mouthpiece of Galileo), Sagredo, who represented the interested but less well-informed reader, and Simplicio, who argued for Aristotle, and whose arguments were possibly a parody of those made by Pope Urban VIII.