Liberty Party (United States, 1840)

They attempted to work within the federal system created by the United States Constitution to diminish the political influence of the Slave Power and advance the cause of universal emancipation and an integrated, egalitarian society.

[4] In 1847 party leaders favoring a coalition with antislavery Conscience Whigs and Barnburner Democrats succeeded in nominating John P. Hale for president over Gerrit Smith, the candidate of the radical Liberty League.

The success of the "questioning system" proved fleeting, however, as abolitionists discovered candidates frequently would issue antislavery pledges during a campaign, only to abandon their commitments once elected.

While William Lloyd Garrison remained a prominent and influential figure, the failure of moral suasion discredited the approach of the AASS, and by 1844, "the Liberty Party was the major vehicle for serious abolitionist sentiment in every state.

While Independent Democrats like Hale and Conscience Whigs like John Quincy Adams and Joshua Reed Giddings might share some abolitionist priorities, they would still campaign for their parties' proslavery national candidates and did not support immediate, universal emancipation.

The Liberty Party has not been organized merely for the overthrow of slavery; its first decided effort must, indeed, be directed against slave-holding as the grossest and most revolting manifestation of despotism, but it will also carry out the principle of equal rights into all its practical consequences and applications, and support every just measure conducive to individual and social freedom.

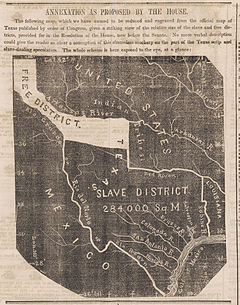

Martin Van Buren, the early presumptive nominee of the Democratic Party, opposed annexation on the grounds that it would inflame sectional tensions between the free and slave states.

After 1844, Liberty leaders including Smith and Goodell began to argue that the Constitution was in fact antislavery and had been wrongly construed by proslavery judges and elected officials.

By nominating Hale, the delegates had chosen to fight the next campaign on the narrow ground of opposition to slavery's westward extension, rather than the broader reform agenda advocated by the Liberty League.

Though publicly neutral on the slavery question, Taylor was a slaveholder and a career military man who had risen to prominence in a war many northern Whigs had fervently opposed.

Faced with a choice between a proslavery Democrat and a slaveholding Whig, the moment seemed ripe for a union of antislavery men of all parties like what Chase and the coalitionists had long anticipated.

An ad hoc national convention held at Buffalo nominated Smith and Charles C. Foote on a platform embracing the radical implications of the Liberty League's "one idea" philosophy.

Declaring themselves unalterably committed to the cause of human freedom and the destruction of all arbitrary distinctions of race, class, and gender, they endorsed the extension of universal suffrage, temperance, land reform, the abolition of the army and navy, and a general boycott of all consumer goods connected with slavery.

They expressed solidarity with the French Revolution of 1848 and the recent escape attempt by 177 enslaved people in Washington, D.C.[39] Almost all Liberty members, however, eventually followed Joshua Leavitt into the Free Soil Party.

In 1854, during the vitriolic debates over the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, he penned the Appeal of the Independent Democrats and helped to arrange the fusion of the Free Soilers with other opponents of the Kansas–Nebraska Act to form the Republican Party.

While the Liberty leaders' embrace of direct political action eventually drew them into conflict with William Lloyd Garrison, they shared the immediatist perspective of the AASS and rejected the equivocal position maintained by the American Colonization Society.

Nonetheless, the electoralism of the Liberty leaders reflected significant pragmatic and philosophical differences with the Garrisonians respecting the fundamental nature of the United States Constitution and the problem of slavery itself that split the AASS in 1840.

Garrison held that the Constitution was an irredeemably proslavery document and strongly opposed abolitionist entry into politics, remaining wholly committed to the strategy of moral suasion.

Douglass came ultimately to accept this view by the time of his celebrated Fourth of July oration in 1852, when he described the Constitution as a "glorious liberty document" whose true reading had been subverted by corrupt proslavery officials.

Influenced by the involvement of Black abolitionists like Henry Highland Garnet, Liberty meetings sometimes adopted resolutions expressing support for slave rebellions such as the Creole case, a step which the Garrisonians were not willing to endorse.

Waters sees the influence of the liberal concept of "possessive individualism" on the abolitionist movement, its language "an interesting mixture of Christianity and commerce" with roots in 17th century English political thought.

[71][72] Reinhard Johnson notes that from 1841, the Liberty Party "avoided much of the religious rhetoric and imagery" commonly associated with the abolitionist movement and instead emphasized its opposition to the political influence of the Slave Power.

He assessed that moral arguments appealed to only a narrow swath of the electorate, concentrated in areas of Yankee settlement, while the constitutional violations and economic malaise associated with the domination of the Slave Power posed more compelling reasons for white voters to abandon their former partisan allegiances.

The destruction of the Slave Power thus appeared as at once the most immediate and practical means of stopping the spread of slavery nationally, a politically useful argument for recruiting new voters to the antislavery cause, and a desirable object in its own right.

The convention expressed support for the efforts of free people of color to achieve equal political and civil rights and declared that the United States military should not be used to suppress an enslaved rebellion.

It endorsed universal suffrage, a progressive income tax, an end to private ownership of land, prohibition against extrajudicial oaths administered by secret societies, temperance, abolition of the army and navy, free trade, a ten-hour workday, and a homestead exemption.

Lee Benson described the profile of the Liberty electorate in western New York as men from "small, moderately prosperous Yankee farming communities," typically individuals of "considerable standing" and "much better than average education," who "shared a common set of 'radical religious beliefs.

'"[79] However, Reinhard Johnson notes that Protestant evangelicals in the Liberty Party were "liturgically indistinguishable" from their brethren who did not become political abolitionists, while local leaders struggled to make ends meet and "often lived on the edge of poverty."

Garnett, Ward, and Henry Bibb were among the party's foremost advocates and regularly clashed with Black Garrisonians who question the motives and strategy of political abolitionists.

[90] The Henry County Female Anti-Slavery Society was the foremost Liberty mouthpiece in Indiana; the preamble and resolutions adopted by the society at its 1841 meeting expressly affirmed "that it is our duty to endeavor by all reasonable means to persuade our fathers, husbands and brothers to make use of the their elective franchise to place men in office who will remove these evils [slavery and racial prejudice] by the introduction of righteous and just laws into the civil code of our country.