Library of Alexandria

The Library quickly acquired many papyrus scrolls, owing largely to the Ptolemaic kings' aggressive and well-funded policies for procuring texts.

[11] Many important and influential scholars worked at the Library during the third and second centuries BC, including: Zenodotus of Ephesus, who worked towards standardizing the works of Homer; Callimachus, who wrote the Pinakes, sometimes considered the world's first library catalog; Apollonius of Rhodes, who composed the epic poem the Argonautica; Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who calculated the circumference of the earth within a few hundred kilometers of accuracy; Hero of Alexandria, who invented the first recorded steam engine; Aristophanes of Byzantium, who invented the system of Greek diacritics and was the first to divide poetic texts into lines; and Aristarchus of Samothrace, who produced the definitive texts of the Homeric poems as well as extensive commentaries on them.

This decline began with the purging of intellectuals from Alexandria in 145 BC during the reign of Ptolemy VIII Physcon, which resulted in Aristarchus of Samothrace, the head librarian, resigning and exiling himself to Cyprus.

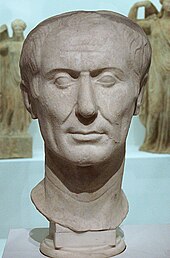

The Library, or part of its collection, was accidentally burned by Julius Caesar during his civil war in 48 BC, but it is unclear how much was actually destroyed and it seems to have either survived or been rebuilt shortly thereafter.

The geographer Strabo mentions having visited the Mouseion in around 20 BC, and the prodigious scholarly output of Didymus Chalcenterus in Alexandria from this period indicates that he had access to at least some of the Library's resources.

The Serapeum was vandalized and demolished in 391 AD under a decree issued by bishop Theophilus of Alexandria, but it does not seem to have housed books at the time, and was mainly used as a gathering place for Neoplatonist philosophers following the teachings of Iamblichus.

[4][5] To support this endeavor, they were well positioned as Egypt was the ideal habitat for the papyrus plant, which provided an abundant supply of materials needed to amass their knowledge repository.

[2] In around 295 BC, Demetrius may have acquired early texts of the writings of Aristotle and Theophrastus, which he would have been uniquely positioned to do since he was a distinguished member of the Peripatetic school.

[37] According to the Greek medical writer Galen, under the decree of Ptolemy II, any books found on ships that came into port were taken to the library, where they were copied by official scribes.

[40] In addition to collecting works from the past, the Mouseion which housed the Library also served as home to a host of international scholars, poets, philosophers, and researchers, who, according to the first-century BC Greek geographer Strabo, were provided with a large salary, free food and lodging, and exemption from taxes.

[51] According to two late and largely unreliable biographies, Apollonius was forced to resign from his position as head librarian and moved to the island of Rhodes (after which he takes his name) on account of the hostile reception he received in Alexandria to the first draft of his Argonautica.

[56][51][57] Eratosthenes also produced a map of the entire known world, which incorporated information taken from sources held in the Library, including accounts of Alexander the Great's campaigns in India and reports written by members of Ptolemaic elephant-hunting expeditions along the coast of East Africa.

[58] Eratosthenes believed that the setting of the Homeric poems was purely imaginary and argued that the purpose of poetry was "to capture the soul", rather than to give a historically accurate account of actual events.

[59] A scholar named Ptolemy Epithetes wrote a treatise on wounds in the Homeric poems, a subject straddling the line between traditional philology and medicine.

[46] He earned a reputation as the greatest of all ancient scholars and produced not only texts of classic poems and works of prose, but full hypomnemata, or long, free-standing commentaries, on them.

[78][83][b] Other scholars branched out and began writing commentaries on the poetic works of postclassical authors, including Alexandrian poets such as Callimachus and Apollonius of Rhodes.

His soldiers set fire to some of the Egyptian ships docked in the Alexandrian port while trying to clear the wharves to block the fleet belonging to Cleopatra's brother Ptolemy XIV.

[85][82][8] The first-century AD Roman playwright and Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger quotes Livy's Ab Urbe Condita Libri, which was written between 63 and 14 BC, as saying that the fire started by Caesar destroyed 40,000 scrolls from the Library of Alexandria.

[61][82][8][86] The Greek Middle Platonist Plutarch (c. 46–120 AD) writes in his Life of Caesar that, "[W]hen the enemy endeavored to cut off his communication by sea, he was forced to divert that danger by setting fire to his ships, which, after burning the docks, thence spread on and destroyed the great library.

"[87][88][8] The Roman historian Cassius Dio (c. 155 – c. 235 AD), however, writes: "Many places were set on fire, with the result that, along with other buildings, the dockyards and storehouses of grain and books, said to be great in number and of the finest, were burned.

[88][82] Plutarch himself notes that his source for this anecdote was sometimes unreliable and it is possible that the story may be nothing more than propaganda intended to show that Mark Antony was loyal to Cleopatra and Egypt rather than to Rome.

[88] Edward J. Watts argues that Mark Antony's gift may have been intended to replenish the Library's collection after the damage to it caused by Caesar's fire roughly a decade and a half prior.

[95] The Greek writer Philostratus records that the emperor Hadrian (ruled 117–138 AD) appointed the ethnographer Dionysius of Miletus and the sophist Polemon of Laodicea as members of the Mouseion, even though neither of these men is known to have ever spent any significant amount of time in Alexandria.

[100] Later scholars—beginning with Father Eusèbe Renaudot in his 1713 translation of the History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria—are skeptical of these stories, given the range of time that had passed before they were written down and the political motivations of the various writers.

[101][102][103] Roy MacLeod, for example, points out that the story first appeared 500 years after the event, that John Philoponus was almost certainly dead by the time of the conquest of Egypt and that both the Great Library of Alexandria and the Mouseion were likely long gone by then.

[104] According to Diana Delia, "Omar's rejection of pagan and Christian wisdom may have been devised and exploited by conservative authorities as a moral exemplum for Muslims to follow in later, uncertain times, when the devotion of the faithful was once again tested by proximity to nonbelievers".

[105] The historian Bernard Lewis suggests the myth came into existence during the reign of Saladin in order to justify the Sunni Ayyubids' breaking up of the Shia Fatimid collections and library at public auction.

[110] The Neoplatonist philosopher Damascius (lived c. 458 –after 538) records that a man named Olympus came from Cilicia to teach at the Serapeum, where he enthusiastically taught his students the rules of traditional divine worship and ancient religious practices.

[125][126] Rumors spread accusing her of preventing Orestes from reconciling with Cyril[125][127] and, in March of 415 AD, she was murdered by a mob of Christians, led by a lector named Peter.

[130][131] British Egyptologist Charlotte Booth notes that many new academic lecture halls were built in Alexandria at Kom el-Dikka shortly after Hypatia's death, indicating that philosophy was clearly still taught in Alexandrian schools.