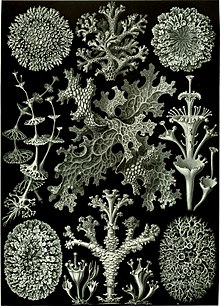

Lichen anatomy and physiology

The fungus surrounds the algal cells, often enclosing them within complex fungal tissues unique to lichen associations.

It extends the ecological range of both partners but is not always obligatory for their growth and reproduction in natural environments, since many of the algal symbionts can live independently.

A prominent example is the alga Trentepohlia which forms orange-coloured populations on tree trunks and suitable rock faces.

Lichen propagules (diaspores) typically contain cells from both partners, although the fungal components of so-called "fringe species" rely instead on algal cells dispersed by the “core species.”[5] Lichen associations may be examples of mutualism, commensalism or even parasitism,[citation needed] depending on the species.

In tests, lichen survived and showed remarkable results on the adaptation capacity of photosynthetic activity within the simulation time of 34 days under Martian conditions in the Mars Simulation Laboratory (MSL) maintained by the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

[6][7] Living as a symbiont in a lichen appears to be a successful way for a fungus to derive essential nutrients, as about 20% of all fungal species have acquired this mode of life.

[9] The largest number of lichenized fungi occur in the Ascomycota, with about 40% of species forming such an association.

The autotrophic symbionts occurring in lichens are a wide variety of simple, photosynthetic organisms commonly and traditionally known as algae.

Approximately 100 species of photosynthetic partners from 40 genera and five distinct classes (prokaryotic: Cyanophyceae; eukaryotic: Trebouxiophyceae, Phaeophyceae, Chlorophyceae) have been found to associate with the lichen-forming fungi.

The thalli produced by a given fungal symbiont with its differing partners will be similar, and the secondary metabolites identical, indicating that the fungus has the dominant role in determining the morphology of the lichen.

[13] "Clorococcoid" means a green alga (Chlorophyta) that has single cells that are globose, which is common in lichens.

[14] These were once classified in the order Chlorococcales, which you may find stated in older literature, but new DNA data shows many independent lines of evolution exist among this formerly large taxonomic group.

Another cyanolichen group, the jelly lichens ( e.g., from the genera Collema or Leptogium) are large and foliose (e.g., species of Peltigera, Lobaria, and Degelia).

Many of these characterize the Lobarion communities of higher rainfall areas in western Britain, e.g., in the Celtic Rainforest.