Limestone

[8] Most limestone is otherwise chemically fairly pure, with clastic sediments (mainly fine-grained quartz and clay minerals) making up less than 5%[9] to 10%[10] of the composition.

[11] Limestone often contains variable amounts of silica in the form of chert or siliceous skeletal fragments (such as sponge spicules, diatoms, or radiolarians).

Aragonite skeletal grains are typical of molluscs, calcareous green algae, stromatoporoids, corals, and tube worms.

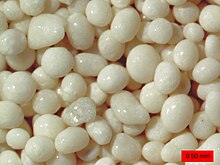

Ooids form in high-energy environments, such as the Bahama platform, and oolites typically show crossbedding and other features associated with deposition in strong currents.

[20][21] Oncoliths resemble ooids but show a radial rather than layered internal structure, indicating that they were formed by algae in a normal marine environment.

Extraclasts are uncommon, are usually accompanied by other clastic sediments, and indicate deposition in a tectonically active area or as part of a turbidity current.

Dolomite is also soft but reacts only feebly with dilute hydrochloric acid, and it usually weathers to a characteristic dull yellow-brown color due to the presence of ferrous iron.

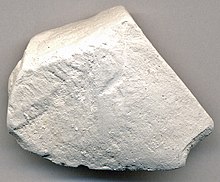

[9] Impurities (such as clay, sand, organic remains, iron oxide, and other materials) will cause limestones to exhibit different colors, especially with weathered surfaces.

[33] True marble is produced by recrystallization of limestone during regional metamorphism that accompanies the mountain building process (orogeny).

Robert L. Folk developed a classification system that places primary emphasis on the detailed composition of grains and interstitial material in carbonate rocks.

[38] Travertine is a term applied to calcium carbonate deposits formed in freshwater environments, particularly waterfalls, cascades and hot springs.

[40] Limestone forms when calcite or aragonite precipitate out of water containing dissolved calcium, which can take place through both biological and nonbiological processes.

Diagenesis is the likely origin of pisoliths, concentrically layered particles ranging from 1 to 10 mm (0.039 to 0.394 inches) in diameter found in some limestones.

Pisoliths superficially resemble ooids but have no nucleus of foreign matter, fit together tightly, and show other signs that they formed after the original deposition of the sediments.

Cementing accelerates after the retreat of the sea from the depositional environment, as rainwater infiltrates the sediment beds, often within just a few thousand years.

This process dissolves minerals from points of contact between grains and redeposits it in pore space, reducing the porosity of the limestone from an initial high value of 40% to 80% to less than 10%.

[54] When overlying beds are eroded, bringing limestone closer to the surface, the final stage of diagenesis takes place.

Large moundlike features in a limestone formation are interpreted as ancient reefs, which when they appear in the geologic record are called bioherms.

[65] Deposition is also favored on the seaward margin of shelves and platforms, where there is upwelling deep ocean water rich in nutrients that increase organic productivity.

[66] The lack of deep sea limestones is due in part to rapid subduction of oceanic crust, but is more a result of dissolution of calcium carbonate at depth.

[76] Limestones also show distinctive features such as geopetal structures, which form when curved shells settle to the bottom with the concave face downwards.

Geologists use geopetal structures to determine which direction was up at the time of deposition, which is not always obvious with highly deformed limestone formations.

[79] Mud mounds are found throughout the geologic record, and prior to the early Ordovician, they were the dominant reef type in both deep and shallow water.

[81][82][83] The extent of organic reefs has varied over geologic time, and they were likely most extensive in the middle Devonian, when they covered an area estimated at 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi).

While draining, water and organic acid from the soil slowly (over thousands or millions of years) enlarges these cracks, dissolving the calcium carbonate and carrying it away in solution.

Examples include the Rock of Gibraltar,[88] the Burren in County Clare, Ireland;[89] Malham Cove in North Yorkshire and the Isle of Wight,[90] England; the Great Orme in Wales;[91] on Fårö near the Swedish island of Gotland,[92] the Niagara Escarpment in Canada/United States;[93] Notch Peak in Utah;[94] the Ha Long Bay National Park in Vietnam;[95] and the hills around the Lijiang River and Guilin city in China.

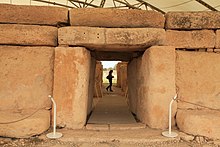

Going back to the Late Preclassic period (by 200–100 BCE), the Maya civilization (Ancient Mexico) created refined sculpture using limestone because of these excellent carving properties.

Other problems were high capital costs on plants and facilities due to environmental regulations and the requirement of zoning and mining permits.

[104] These two dominant factors led to the adaptation and selection of other materials that were created and formed to design alternatives for limestone that suited economic demands.

This allowed limestone to no longer be classified as critical as replacement substances increased in production; minette ore is a common substitute, for example.