Life of Buddha in art

There is also a large body of Jataka tales, relating events from the many previous lives of Gautama Buddha, which were often subjects in Gandhara and early Indian art.

[6] In post-Gupta India a number of the most important scenes were grouped together; again stone reliefs on steles have survived, but painted versions only from later periods, and mostly from other countries.

It was twelve years before a child was born, by which time Siddharta, then aged 29, had decided to renounce the life his father wanted for him, for that of a Śramaṇa ascetic.

[16] In the texts the life of the Buddha is followed with enormous interest by large numbers of gods and other figures, who sometimes come to earth to intervene or merely witness, as shown in depictions of the Great Departure.

Maya standing with her right hand over her head, holding a curving bough, is the indispensable part of the iconography; this was a pose familiar in Indian art, often adopted by yakshini tree-spirits.

He received a princely education, and scenes of him learning martial arts, riding, archery and swimming may be found in extended cycles, as in two early Tibetan thankas.

[39] Some Gandharan reliefs show him being driven to school in a small cart pulled by rams, perhaps reflecting local elite life; this detail is not in surviving early texts.

[42] East Asian depictions place more emphasis on desk work, no doubt reflecting the local importance of passing the Imperial examinations of China, which began around the 6th century.

His father wished him to take the secular path, from the prophetic options offered before his birth, but a visit by a delegation of gods, urged him to pursue the life of dharma.

[51] The biographies record a moment when Siddharta was repulsed by the appearance of his female retinue, one or more of whom were sprawled on the floor asleep, concluding "It is true, I live amid a cemetery".

The birth of his son, fulfilling his duty to provide an heir for the royal line, was apparently the trigger for Siddharta's abandonment of palace life to become an ascetic.

The last of these before the Enlightenment was when Siddharta met a grass-cutter and obtained from him long kusa grass (desmostachya bipinnata) to sit on as he meditated (of a type often used by Indian religious for this purpose).

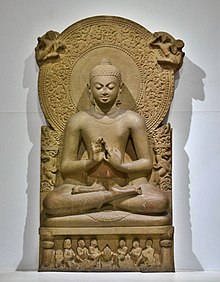

Buddha is always shown seated in the lotus position, reaching the fingers of his right hand down to touch the ground, which is called the bhūmisparśa or "earth witness" mudra.

[77] The account in a biography much used in South-East Asia has Pṛthivi answering Buddha's call by wringing out her hair, which produces a great flood that sweeps Mara's army away, and this may be shown in depictions, especially from Thailand and Cambodia.

[83] Towards the end of the period (week five or six) there was very heavy rain and the giant nagaraja or cobra snake-king, Mucalinda sheltered the Buddha with the hoods of his several heads.

[89] For the remainder of Buddha's life he travelled around a relatively restricted area of the Indo-Gangetic plain, preaching and making converts, organizing his growing sangha or body of followers, and sometimes receiving gifts and offerings from various Indians, high and low.

[95] The large donation by the rich merchant Anathapindada (birth name Sudatta) founded the important early vihara (monastery) of Jetavana; he was supposed to have decided the amount by covering the proposed site with gold coins.

They seem to have been a group of ascetics practicing fire rituals in a form of Vedic religion, with a temple at Uruvilva on the Phalgu River, near where Buddha had been for his most austere period.

In some versions the Buddha initially rejected the honey because it had bee larvae, ants or other insects in it, but after the monkey carefully removed these with a twig his gift was accepted.

He left his begging bowl in the city when he departed, and this, which became an important cetiya or relic, is the indispensable identifying element in the most reduced images, when even the monkey is not shown.

The monkey, overcome with excitement when his gift is accepted, fell or jumped down a well in some versions, but was later saved and turned into a deva,[112] or was reborn as a human who joined Buddha's sangha as a monk.

It is normally depicted in stele groups across the centre of the top, above the main figures, with a reclining Buddha with his head to the left, usually on a raised couch or bed.

As many followers as space allow are crowded round the bed, in early versions making extravagant gestures of grief; these return in later Japanese paintings.

[122] A rather small figure is often shown, typically facing out, sitting in front of the bed, usually in rather shallow relief; this is the Buddha's last convert, the ascetic Subhadra (or Sucandra).

[125] The texts (the Pali Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta and Sanskrit-based Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra are the earliest) say he lived to be eighty, but he is shown as young, as he is in all depictions of him as an adult.

[128] A 19th-century painting in the British Museum from the shunga erotic genre represents the persons present as penises and vulvas; other images show famous actors as the characters.

A scene of the Dream of Queen Maya will lack the elephant, and one of The Great Departure will have a riderless horse, surrounded by the usual crowd of heavenly figures.

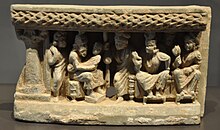

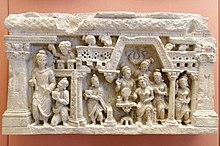

[140] The Gandharan method of telling the story in a number of separate scenes, clearly demarcated by frames or columns, is a "definite borrowing from Roman art"; it is seen in depictions of imperial careers.

[147] The Indian tradition of Buddhist paintings on cloth (pata) has left no survivals, but its descendents can undoubtedly be seen in the thankas of Tibetan and Himalayan art, especially earlier ones.

After a few centuries images of these figures by themselves become popular,[149] and eventually more common than those of Gautama Buddha in many areas where Mahayana Buddhism dominated, reflecting changes in Buddhist thought and meditational and devotional practice.