Lihyan

The term "Dedanite" usually describes the earlier phase of the history of this kingdom since their capital name was Dedan, which is now called Al-'Ula oasis located in northwestern Arabia, some 110 km southwest of Teima, both cities located in modern-day Saudi Arabia, while the term "Lihyanite" describes the later phase.

Nonetheless, in modern historiography, the terms are often employed with a chronological meaning, Dedan referring to the earlier period and Lihyan the later of the same civilization.

[9] Dadān represents the best approximation of the original pronunciation, while the more traditional spelling Dedan reflects the form found in the Hebrew Bible.

[10] Scholars have long grappled to establish a reliable timeline for the kingdoms of Lihyan and Dadan; numerous attempts were made to construct a secure chronology, but none of them so far came to fruition.

The main source of information regarding the date of the Lihyanite kingdom emanates from the collection of inscriptions within the precinct of Dadān and its contiguous environs.

[12] Thus, when attempting to piece together the history of the kingdom, previous historians have heavily relied on epigraphic records and sometimes scant archaeological remains due to the lack of comprehensive excavations.

The absence of specific references to well-dated external events in these local inscriptions has made it challenging to establish a definitive and uncontested chronology.

In his long chronology, F. Winnett agrees with Caskel that the Lihyanites succeeded an earlier, lesser-known local dynasty whose members were referred to as ‘king of Dadān’, which he places its beginning in the 6th century BC.

[18] If we accept these two main assumptions — the interpretation and tentative dating of the text to the Achaemenid period and the equation of Gashm b. Shahr with Geshem the Arab and Geshem father of Qainū — then we have a likely limit in the second half of the fifth century BC after which the Lihyanites must have emerged as an independent kingdom,[12] possibly due to the fragmentation of the Qedarite realm.

[12] Overall, what we can discern is that the Lihyanite kingdom most likely came into being after the arrival of Nabonidus in north-west Arabia in 552 BC, as 'king of Dadān' is still mentioned during his Arabian campaign.

[12] Although no more precise terminus post quem can be provided to us by the Dadanitic inscriptions, they do grant us, however, the means to estimate the minimum duration of the Lihyanite kingdom.

[23] Biblical accounts refer to Dadān as early as the sixth century BC, mentioning its ‘caravans’ and ‘saddlecloth’ trade.

[24] The earliest reference to Lihayn appears in a Sabaic document recounting the travels of a Sabaean merchant to Cyprus through Dadān, the ‘cities of Judah’, and Gaza.

Dated to the first half of the 6th century BC due to a mention of ‘war between Chaldea and Ionia,’ interpreted as a Neo-Babylonian campaign in Cilicia, the text treats Lihyan separately from Dadān; this suggests that they might have been a tribe at that time, conceivably part of the Qedarite federation, not yet established as a kingdom with Dadān as its capital.

[32] Lihyan’s emergence as a kingdom is traditionally dated to the 4th century BC on the basis of a widely considered key inscription (JSLih 349) which mentions a fḥt (from Aramaic pḥt; lit.

[18] He also noted that the inscription references a governor (fḥt) of Dadān without any mention of Lihyan, indicating that the Lihyanite kingdom did not exist when the text was written.

Given the widespread occurrence of the name gšm in northern Arabia, this association is doubtful and does not provide a reliable basis for dating the text.

[15] Considering the acknowledged scarcity of any secure chronological anchors, current academics generally adhere to the traditional date for the establishment of the Lihyanite kingdom.

[33] According to M. C. A. Macdonald, J. Rohmer and G. Charloux persuasively argued for a revised chronological scheme where the Lihyanite kingdom lasted from the late 6th to the mid-3rd century BC in light of the new finds.

Their cooperative efforts revealed new Aramaic inscriptions dated according to the reign of multiple Lihyanite kings, representing the first records of Lihyanite rulers outside of Dadān;[41] those rulers are: an unnamed king, who was the son of a certain individual named psg, likely the same psgw Šahrū with asserted ties to the kings of Lihyan, signifying the ascendancy of psgw family at Dadān and Taymāʾ; ʿUlaym/Gulaym Šahrū; Lawḏān (I), confirmed through an inscription by his governor Natir-Il commemorating the construction of a city gate under his rule; and Tulmay, son of Han-ʾAws, mentioned in four inscriptions (years 4, 20, 30, and 40) from the temple of Taymāʾ.

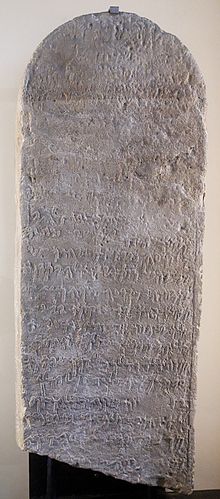

Discovered in 1884 by C. Huber and J. Euting, the stele’s front features an Imperial Aramaic inscription detailing the introduction of a new deity, ṣlm hgm, the designation of its priest, and the allocation of properties for the temple.

Therefore the gods (12) Taymāʾ have granted to Ṣalmšēzeb, the son of Petosiris, (13) and to his descendants in the house of Ṣalm of HGM (the following gift).

Newly discovered epigraphic evidence has prompted the latter author to lean towards an earlier date for the stele, around 500 BC, which opens up the possibility of a reduced duration of Achaemenid suzerainty in the oasis.

[43] Regardless of dating uncertainties, the key question revolves around whether the Taymāʾ stone refers to a foreign king;[43] C. Edens and G. Bawden proposed, more than 30 years ago, that the missing name might be that of a local ruler.

[46] It stands out as the sole inscription mentioning the Lihyanite dynasty that was found in a clear archaeological setting, discovered on a cultic platform within the early shrine of the Qaṣr al-Ḥamrāʾ complex.

[46] The stele’s lower half bears an inscription that reads: [šnt ... bbr]t tymʾ (2) [h]qym pṣgw šhrw br (3) [m]lky lḥyn hʿly by[t] (4) ṣlm zy rb wmrḥbh w (5) [h]qym krsʾʾznh qdm (6) ṣlm zy rb lmytb šnglʾ (7) wʾšymʾ ʾlhy tymʾ (8) lḥyy nfš pṣgw (9) šhrw wzrʿh mrʾ [yʾ] (10)[w]l[ḥ]yy npšh zy [lh] (lit. '

[17] In any case, the text proves the existence of the Lihyanite kingdom when it was written—which probably extended to Taymāʾ— before the mid-4th century BC as indicated by radiocarbon dating of bone samples from the main phase of the shrine where the stele was found in a clear archaeological setting.

[46] Indeed, the stele exhibits a distinct Egyptian influence through iconography, featuring motifs like the Udjat eye and the winged sun-disk.

The first, Cascel relied on Strabo's accounts of the disastrous Roman expedition on Yemen that was led by Aelius Gallus from 26 to 24 BC.

The Lihyanites restored their independence under the rule of Han'as ibn Tilmi, a member of the former royal family that predated the Nabataean invasion.

Translation: ʿĀṣī king of Dadān made (it) for (the deity) Ṭaḥlān"