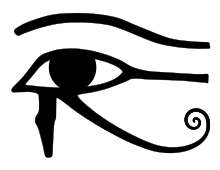

Eye of Horus

Egyptologists have long believed that hieroglyphs representing pieces of the symbol stand for fractions in ancient Egyptian mathematics, although this hypothesis has been challenged.

[7] Other Egyptologists, however, argue that no text clearly equates the eyes of Horus with the sun and moon until the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC);[8] Rolf Krauss argues that the Eye of Horus originally represented Venus as the morning star and evening star and only later became equated with the moon.

[10] The Pyramid Texts, which date to the late Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC), are one of the earliest sources for Egyptian myth.

The texts often mention the theft of Horus's eye along with the loss of Set's testicles, an injury that is also healed.

In most of these texts, the eye is restored by another deity, most commonly Thoth, who was said to have made peace between Horus and Set.

[14] In the Book of the Dead from the New Kingdom, Set is said to have taken the form of a black boar when striking Horus's eye.

[14] In Papyrus Jumilhac, a mythological text from early in the Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BC), Horus's mother Isis waters the buried pair of eyes, causing them to grow into the first grape vines.

[4][20] It is unclear whether the term wḏꜣt refers to the eye that was destroyed and restored, or to the one that Set left unharmed.

[21] Upon becoming king after Set's defeat, Horus gives offerings to his deceased father, thus reviving and sustaining him in the afterlife.

This act was the mythic prototype for the offerings to the dead that were a major part of ancient Egyptian funerary customs.

[25] The eye's restorative power meant the Egyptians considered it a symbol of protection against evil, in addition to its other meanings.

The Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson suggests that the curling line is derived from the facial markings of the cheetah, which the Egyptians associated with the sky because the spots in its coat were likened to stars.

[34] Amulets in the shape of the wedjat eye first appeared in the late Old Kingdom and continued to be produced up to Roman times.

It is one of the few types commonly found on Old Kingdom mummies, and it remained in widespread use over the next two thousand years, even as the number and variety of funerary amulets greatly increased.

[35] Wedjat amulets were made from a wide variety of materials, including Egyptian faience, glass, gold, and semiprecious stones such as lapis lazuli.

Rubrics for ritual spells often instruct the practitioner to draw the wedjat eye on linen or papyrus to serve as a temporary amulet.

Coffins of the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC) and Middle Kingdom often included a pair of wedjat eyes painted on the left side.

Similarly, eyes of Horus were often painted on the bows of boats, which may have been meant to both protect the vessel and allow it to see the way ahead.

In some periods of Egyptian history, only deities or kings could be portrayed directly beneath the winged sun symbol that often appeared in the lunettes of stelae, and Eyes of Horus were placed above figures of common people.

In 1911, the Egyptologist Georg Möller noted that on New Kingdom "votive cubits", inscribed stone objects with a length of one cubit, these hieroglyphs were inscribed together with similarly shaped symbols in the hieratic writing system, a cursive writing system whose signs derived from hieroglyphs.

[47] Jim Ritter, a historian of science and mathematics, analyzed the shape of the hieratic signs through Egyptian history in 2002.

He concluded that "the further back we go the further the hieratic signs diverge from their supposed Horus-eye counterparts", thus undermining Möller's hypothesis.

He also reexamined the votive cubits and argued that they do not clearly equate the Eye of Horus signs with the hieratic fractions, so even Peet's weaker form of the hypothesis was unlikely to be correct.

The hieroglyphs for parts of the eye (𓂁, 𓂂, 𓂃, 𓂄, 𓂅, 𓂆, 𓂇) are listed as U+13081 through U+13087.