Lime mortar

[3] With the introduction of Portland cement during the 19th century, the use of lime mortar in new constructions gradually declined.

This was largely due to the ease of use of Portland cement, its quick setting, and high compressive strength.

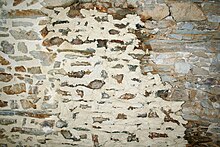

However, the soft and porous properties of lime mortar provide certain advantages when working with softer building materials such as natural stone and terracotta.

[4] Despite its enduring utility over many centuries (Roman concrete), lime mortar's effectiveness as a building material has not been well understood; time-honoured practices were based on tradition, folklore and trade knowledge, vindicated by the vast number of old buildings that remain standing.

[6] Lime comes from Old English lim ('sticky substance, birdlime, mortar, cement, gluten'), and is related to Latin limus ('slime, mud, mire'), and linere ('to smear').

[9] Traditional Indian structures were built with lime mortar, some of which are more than 4,000 years old (such as Mohenjo-daro, a heritage monument of Indus Valley civilization in Pakistan).

Vitruvius, a Roman architect, provided basic guidelines for lime mortar mixes.

The Romans created hydraulic mortars that contained lime and a pozzolan such as brick dust or volcanic ash.

[11] Lime mortar today is primarily used in the conservation of buildings originally built using it, but may be used as an alternative to ordinary portland cement.

Non-hydraulic lime is produced from a high purity source of calcium carbonate such as chalk, limestone, or oyster shells.

[citation needed] As well as calcium-based limestone, dolomitic limes can be produced which are based on calcium magnesium carbonate.

A frequent source of confusion regarding lime mortar stems from the similarity of the terms hydraulic and hydrated.

There is an argument that a lime putty which has been matured for an extended period (over 12 months) becomes so stiff that it is difficult to work.

A hydrated lime will produce a material which is not as "fatty”, being a common trade term for compounds have a smoother buttery texture when worked.

In practice, lime mortars are often protected from direct sunlight and wind with damp hessian sheeting or sprayed with water to control the drying rates.

In the tidewater region of Maryland and Virginia, oyster shells were used to produce quicklime during the colonial period.

Burning shells in a rick is something that Colonial Williamsburg and the recreation of Ferry Farm have had to develop from conjecture and in-the-field learning.

The rick that they constructed consists of logs set up in a circle that burn slowly, converting oysters that are contained in the wood pile to an ashy powder.

When a stronger lime mortar is required, such as for external or structural purposes, a pozzolan can be added, which improves its compressive strength and helps to protect it from weathering damage.

Pozzolans include powdered brick, heat treated clay, silica fume, fly ash, and volcanic materials.

A traditional coarse plaster mix also had horse hair added for reinforcing and control of shrinkage, important when plastering to wooden laths and for base (or dubbing) coats onto uneven surfaces such as stone walls where the mortar is often applied in thicker coats to compensate for the irregular surface levels.

A load of mixed lime mortar may be allowed to sit as a lump for some time, without it drying out (it may get a thin crust).

Traditionally on building sites, prior to the use of mechanical mixers, the lime putty (slaked on site in a pit) was mixed with sand by a labourer who would "beat and ram" the mix with a "larry" (a wide hoe with large holes).

When building e.g. roads and railways, the method is more common and widespread (Queen Eufemias street in Central Oslo, E18 at Tønsberg etc.).

A strong Portland cement mix will prevent a free flow of water from a moist to dry area.

Even when the brick is a modern, harder element, repointing with a higher ratio lime mortar may help to reduce rising damp.

The stability and predictability make the mixed mortar more user friendly, particularly in applications where entire wall sections are being laid.

Contractors and designers may prefer mixes that contain Portland due to the increased compressive strength over a straight lime mortar.

As many pre-Portland mix buildings are still standing and have original mortar, the arguments for greater compressive strength and ease of use may be more a result of current practice and a lack of understanding of older techniques.