Linear particle accelerator

[5] Rolf Wideroe discovered Ising's paper in 1927, and as part of his PhD thesis he built an 88-inch long, two gap version of the device.

Using this approach to acceleration meant that Alvarez's first linac was able to achieve proton energies of 31.5 MeV in 1947, the highest that had ever been reached at the time.

[7] The initial Alvarez type linacs had no strong mechanism for keeping the beam focused and were limited in length and energy as a result.

Two of the earliest examples of Alvarez linacs with strong focusing magnets were built at CERN and Brookhaven National Laboratory.

[8] In 1947, at about the same time that Alvarez was developing his linac concept for protons, William Hansen constructed the first travelling-wave electron accelerator at Stanford University.

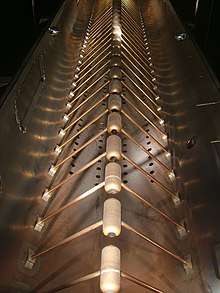

This allowed Hansen to use an accelerating structure consisting of a horizontal waveguide loaded by a series of discs.

[11] In 1970, Soviet physicists I. M. Kapchinsky and Vladimir Teplyakov proposed the radio-frequency quadrupole (RFQ) type of accelerating structure.

RFQs use vanes or rods with precisely designed shapes in a resonant cavity to produce complex electric fields.

[12] Beginning in the 1960s, scientists at Stanford and elsewhere began to explore the use of superconducting radio frequency cavities for particle acceleration.

[13] Superconducting cavities made of niobium alloys allow for much more efficient acceleration, as a substantially higher fraction of the input power could be applied to the beam rather than lost to heat.

With the discovery of strong focusing, quadrupole magnets are used to actively redirect particles moving away from the reference path.

This creates an oscillating electric field (E) in the gap between each pair of electrodes, which exerts force on the particles when they pass through, imparting energy to them by accelerating them.

Additional magnetic or electrostatic lens elements may be included to ensure that the beam remains in the center of the pipe and its electrodes.

Very long accelerators may maintain a precise alignment of their components through the use of servo systems guided by a laser beam.

Induction linear accelerators are considered for short high current pulses from electrons but also from heavy ions.

The concept is comparable to the hybrid drive of motor vehicles, where the kinetic energy released during braking is made available for the next acceleration by charging a battery.

The Brookhaven National Laboratory and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin with the project "bERLinPro" reported on corresponding development work.

In 2014, three free-electron lasers based on ERLs were in operation worldwide: in the Jefferson Lab (US), in the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics (Russia) and at JAEA (Japan).

Experiments involving high power lasers in metal vapour plasmas suggest that a beam line length reduction from some tens of metres to a few cm is quite possible.

The LIGHT program (Linac for Image-Guided Hadron Therapy) hopes to create a design capable of accelerating protons to 200MeV or so for medical use over a distance of a few tens of metres, by optimising and nesting existing accelerator techniques [28] The current design (2020) uses the highest practical bunch frequency (currently ~ 3 GHz) for a Radio-frequency quadrupole (RFQ) stage from injection at 50kVdC to ~5MeV bunches, a Side Coupled Drift Tube Linac (SCDTL) to accelerate from 5Mev to ~ 40MeV and a Cell Coupled Linac (CCL) stage final, taking the output to 200-230MeV.

The acceleration concepts used today for ions are always based on electromagnetic standing waves that are formed in suitable resonators.

The first larger linear accelerator with standing waves - for protons - was built in 1945/46 in the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under the direction of Luis W. Alvarez.

The first electron accelerator with traveling waves of around 2 GHz was developed a little later at Stanford University by W.W. Hansen and colleagues.

(The burst can be held or stored in the ring at energy to give the experimental electronics time to work, but the average output current is still limited.)

Linac-based radiation therapy for cancer treatment began with the first patient treated in 1953 in London, UK, at the Hammersmith Hospital, with an 8 MV machine built by Metropolitan-Vickers and installed in 1952, as the first dedicated medical linac.

In 2019 a Little Linac model kit, containing 82 building blocks, was developed for children undergoing radiotherapy treatment for cancer.

The kit was developed by Professor David Brettle, Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine (IPEM) in collaboration with manufacturers Best-Lock Ltd.

The expected shortages of Mo-99, and the technetium-99m medical isotope obtained from it, have also shed light onto linear accelerator technology to produce Mo-99 from non-enriched Uranium through neutron bombardment.

The aging facilities, for example the Chalk River Laboratories in Ontario, Canada, which still now produce most Mo-99 from highly enriched uranium could be replaced by this new process.

In this way, the sub-critical loading of soluble uranium salts in heavy water with subsequent photo neutron bombardment and extraction of the target product, Mo-99, will be achieved.