Linguistic history of India

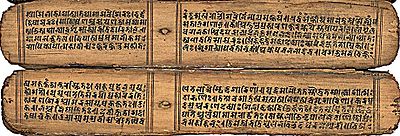

Vedic Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, a large collection of hymns, incantations, and religio-philosophical discussions which form the earliest religious texts in India and the basis for much of the Hindu religion.

It is essentially a prescriptive grammar, i.e., an authority that defines (rather than describes) correct Sanskrit, although it contains descriptive parts, mostly to account for Vedic forms that had already passed out of use in Pāṇini's time.

Prakrit (Sanskrit prākṛta प्राकृत, the past participle of प्राकृ, meaning "original, natural, artless, normal, ordinary, usual", i.e. "vernacular", in contrast to samskrta "excellently made",[citation needed] both adjectives elliptically referring to vak "speech") is the broad family of Indo-Aryan languages and dialects spoken in ancient India.

Whereas in 1630, 80% of the vocabulary was Persian, it dropped to 37% by 1677[9] The British colonial period starting in early 1800s saw standardisation of Marathi grammar through the efforts of the Christian missionary William Carey.

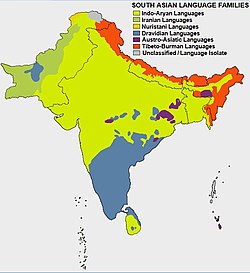

The Dravidian family of languages includes approximately 73 languages[11] that are mainly spoken in southern India and northeastern Sri Lanka, as well as certain areas in Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and eastern and central India, as well as in parts of southern Afghanistan, and overseas in other countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Malaysia and Singapore.

Caldwell coined the term "Dravidian" from the Sanskrit drāvida, related to the word 'Tamil' or 'Tamilan', which is seen in such forms as into 'Dramila', 'Drami˜a', 'Dramida' and 'Dravida' which was used in a 7th-century text to refer to the languages of the southern India.

[18] Other literary works in Old Tamil include two long epics, Cilappatikaram and Manimekalai, and a number of ethical and didactic texts, written between the 5th and 8th centuries.

From the period of the Pallava dynasty onwards, a number of Sanskrit loan-words entered Tamil, particularly in relation to political, religious and philosophical concepts.

Instead, speakers now often use different words or phrases to indicate negation, which may involve changing the structure of the sentence rather than altering the verb forms.

A revival of Tamil literature took place from the late 19th century when works of religious and philosophical nature were written in a style that made it easier for the common people to enjoy.

Vijayanagar Empire which is called the Golden era in the history of medieval India saw a lot of development in all literary form of both Kannada and Telugu.

[61][62] Examples of early Sanskrit-Kannada bilingual copper plate inscriptions (tamarashaasana) are the Tumbula inscriptions of the Western Ganga Dynasty dated 444 AD[63][64] The earliest full-length Kannada tamarashaasana in Old Kannada script (early 8th century) belongs to Alupa King Aluvarasa II from Belmannu, South Kanara district and displays the double crested fish, his royal emblem.

This inscription, dated 575, was found in the districts of Kadapa and Kurnool and is attributed to the Renati Cholas, who broke with the prevailing practice of using Prakrit and began writing royal proclamations in the local language.

The sing-song Telugu rhyme was the work of Jinavallabha, the younger brother of Pampa who was the court poet of Vemulavada Chalukya king Arikesari III.

The language of the Telangana region started to split into a distinct dialect due to Muslim influence: Sultanate rule under the Tughlaq dynasty had been established earlier in the northern Deccan during the 14th century CE.

In the latter half of the 17th century, Muslim rule extended further south, culminating in the establishment of the princely state of Hyderabad by the Asaf Jah dynasty in 1724 CE.

[71] The period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the influence of the English language and modern communication/printing press as an effect of the British rule, especially in the areas that were part of the Madras Presidency.

Literature from this time had a mix of classical and modern traditions and included works by scholars like Kandukuri Viresalingam, Gurazada Apparao, and Panuganti Lakshminarasimha Rao.

[71] Since the 1930s, what was considered an elite literary form of the Telugu language has now spread to the common people with the introduction of mass media like movies, television, radio and newspapers.

Of the trinity of Carnatic music composers, Tyagaraja's and Syama Sastri's compositions were largely in Telugu, while Muttuswami Dikshitar is noted for his Sanskrit texts.

Sri Syama Sastri, the oldest of the trinity, was taught Telugu and Sanskrit by his father, who was the pujari (Hindu priest) at the Meenakshi temple in Madurai.

Renowned Indian scholar Kalidas Nag, after observing the Meitei writings on the handmade papers and agar pieces, opined that the Manipuri script belongs to the pre-Ashokan period.

[81] According to the "Report on the Archaeological Studies in Manipur, Bulletin No-1", a Meitei language copper plate inscription was found to be dated back to the 8th century CE.

The symbols remain undeciphered (in spite of numerous attempts that did not find favour with the academic community), and some scholars classify them as proto-writing rather than writing proper.

Older examples of the Brahmi script appear to be on fragments of pottery from the trading town of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, which have been dated to the early 400 BCE.

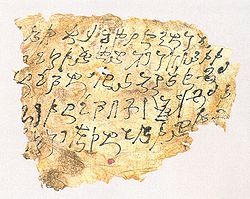

An analysis of the script forms shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indian languages.

The study of the Kharoṣṭhī script was recently invigorated by the discovery of the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, a set of birch-bark manuscripts written in Kharoṣṭhī, discovered near the Afghan city of Haḍḍā (compare Panjabi HAḌḌ ਹੱਡ s. m. "A bone, especially a big bone of dead cattle" referring to the famous mortuary grounds if the area): just west of the Khyber Pass.

It was Kūkai who introduced the Siddham script to Japan when he returned from China in 806, where he studied Sanskrit with Nalanda trained monks including one known as Prajñā.

By the time Kūkai learned this script the trading and pilgrimage routes overland to India, part of the Silk Road, were closed by the expanding Islamic empire of the Abbasids.

In time other scripts, particularly Devanagari replaced it in India, and so Japan was left as the only place where Siddham was preserved, although it was, and is only used for writing mantras and copying sutras.