Linguistic performance

For example, distractions or memory limitations can affect lexical retrieval (Chomsky 1965:3), and give rise to errors in both production and perception.

[9] For example, many linguistic theories, particularly in generative grammar, would propose competence-based explanations for why English speakers would judge the sentence in (1) as not "acceptable".

[10] By contrast, generative theories generally provide performance-based explanations for the acceptability of center embedding sentences like one in (2).

[10][11] In general, performance-based explanations deliver a simpler theory of grammar at the cost of additional assumptions about memory and parsing.

[13][14] Published in 1916, Ferdinand de Saussure's Course in General Linguistics describes language as "a system of signs that express ideas".

[18] This model seeks to explain word order across languages based on avoidance of unnecessary complexity in favour of increased processing efficiency.

Hawkins proposes that speakers prefer to produce (1a) since it has a higher IC-to-word ratio and this leads to faster and more efficient processing.

An additional 71 sequences had PPs of equal length (total n=394) Hawkins argues that the preference for short followed by long phrases applies to all languages that have head-initial structuring.

an additional 91 sequences had ICs of equal length (total n=244) Tom Wasow proposes that word order arises as a result of utterance planning benefiting the speaker.

[19] Wasow illustrates how utterance planning influences syntactic word order by testing early versus late commitment in heavy-NP shifted (HNPS) sentences.

The idea is to examine the patterns of HNPS to determine if the performance data show sentences that are structured to favour the speaker or the listener.

Wasow found that HNPS applied to transitive verb sentences is rare in performance data thus supporting the speaker's perspective.

In his study of the performance data, Wasow found evidence of HNPS frequently applied to prepositional verb structures further supporting the speaker's perspective.

Phonological and semantic errors can be due to the repetition of words, mispronunciations, limitations in verbal working memory, and length of the utterance.

Errors of linguistic performance are perceived by both the speaker and the listener and can therefore have many interpretations depending on the persons judgement and the context in which the sentence was spoken.

[23] According to the proposed speech processing structure by Menn an error in the syntactic properties of an utterance occurs at the positional level.

Another proposal for the levels of speech processing is made by Willem J. M. Levelt to be structured as so:[26] Levelt (1993) states that we as speakers are unaware of most of these levels of performance such as articulation, which includes the movement and placement of the articulators, the formulation of the utterance which includes the words selected and their pronunciation and the rules which must be followed for the utterance to be grammatical.

[27] A study done with Zulu speaking children with a language delay displayed errors in linguistic performance of lacking proper passive verb morphology.

[27] The linguistic components of American Sign Language (ASL) can be broken down into four parts; the hand configuration, place of articulation, movement and other minor parameters.

It allows the signer to articulate what they are wanting to communicate by extending, flexing, bending or spreading the digits; the position of the thumb to the fingers; or the curvature of the hand.

Errors of linguistic performance are judged by the listener giving many interpretations if an utterance is well-formed or ungrammatical depending on the individual.

Three types of brain injuries that could cause errors in performance were studied by Fromkin are dysarthria, apraxia and literal paraphasia.

The speech organs involved can be paralyzed or weakened, making it difficult or impossible for the speaker to produce a target utterance.

Literal paraphasia causes disorganization of linguistic properties, resulting in errors of word order of phonemes.

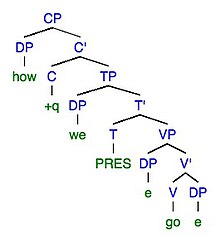

In an elicited production experiment a child, Adam, was prompted to ask questions to an Old Lady[22] The most commonly used measure of syntax complexity is the mean length of utterance, also known as MLU.

Typically, the average MLU corresponds to a child's age due to their increase in working memory, which allows for sentences to be of greater syntactic complexity.

Here is an example of how clause density is measured, using T-units, adapted from Silliman & Wilkinson 2007:[35] Indices track structures to show a more comprehensive picture of a person's syntactic complexity.

[37] This is a commonly applied measurement of syntax for first and second language learners, with samples gathered from both elicited and spontaneous oral discourse.

[36] Similar to Development Sentence Scoring, the Index of Productive Syntax evaluates the grammatical complexity of spontaneous language samples.

For this reason, MLU is initially used in early childhood development to track syntactic ability, then Index of Productive Syntax is used to maintain validity.