Linotype machine

It was a significant improvement over the previous industry standard of letter-by-letter manual typesetting using a composing stick and shallow subdivided trays, called "cases".

The machine revolutionized typesetting and with it newspaper publishing, making it possible for a relatively small number of operators to set type for many pages daily.

Ottmar Mergenthaler invented the Linotype in 1884 alongside James Ogilvie Clephane, who provided the financial backing for commercialization.

In 1876, a German clock maker, Ottmar Mergenthaler, who had emigrated to the United States in 1872,[2] was approached by James O. Clephane and his associate Charles T. Moore, who sought a quicker way of publishing legal briefs.

Perforator operators produced paper tape text at a much higher speed which then was cast by more productive tape-controlled Linotype machines.

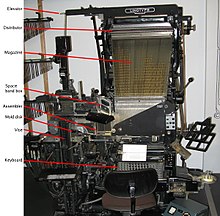

The magazine section is the part of the machine where the matrices are held when not in use, and released as the operator touches keys on the keyboard.

In a linotype machine, the term escapements refers to the mechanisms at the bottom of the magazine that release matrices one at a time as keys are pressed on the keyboard.

Oil in the matrix's path (due to careless maintenance or over-lubrication of nearby parts) can combine with dust, forming a gummy substance that is eventually deposited in the magazine by the matrices.

Once enough text has been entered for the line, the operator depresses the casting lever mounted on the front right corner of the keyboard.

This lifts the completed line in the assembler up between two fingers in the "delivery channel", simultaneously tripping the catch holding it in position.

The blue keys in the middle are punctuation, digits, small capital letters and fixed-width spaces.

A spaceband consists of two wedges, one similar in size and shape to a type matrix, one with a long tail.

The assembler itself is a rail that holds the matrices and spacebands, with a jaw on the left end set to the desired line width.

Motive power for the casting section came from a clutch-operated drive running large cams (the keyboard and distributor sections ran all the time, since distribution may take much longer; however, the front part of the distributor completed its job before the next line of matrices was distributed).

Gas fired pots, such as in the illustration below, were most common in the earlier years, with the pot being thermostatically controlled (high flame when under temperature and low flame when up to temperature), and then a second smaller burner for the mouth and throat heating, with the more modern installations running on 1500 watt electric pots with an initially rheostat controlled mouth and throat heaters (several hundred watts on the electric models).

The temperature was precisely adjusted to keep the lead and tin type metal liquified just prior to being cast.

The Linotype company supplied kerosene heaters and line-shaft operated machines for use in locales without electricity.

The continuous heating of the molten alloy causes the tin and antimony in the mixture to rise to the top and oxidize along with other impurities into a substance called "dross" which must be skimmed off.

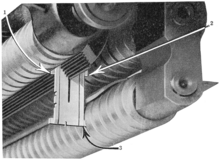

Justification is done by a spring-loaded ram (5) which raises the tails of the spacebands, unless the machine was equipped with a Star Parts automatic hydraulic quadding attachment or Linotype hydraquadder.

[16] If the operator did not assemble enough characters, the line will not justify correctly: even with the spacebands expanded all the way, the matrices are not tight.

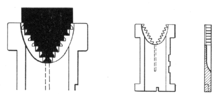

Without such a mechanism, the result would be a squirt of molten type metal spraying out through the gaps between the matrices, creating a time-consuming mess and a possible hazard to the operator.

[17] If a squirt did occur, it was generally up to the operator to grab the hell bucket and catch the flowing lead.

The vise jaws compress the line of matrices so molten metal is prevented from squeezing between the mats on cast.

The jets of molten metal first contact against the casting face of the matrices, and then fills the mold cavity to provide a solid slug body.

The mold disk is sometimes water-cooled, and often air-cooled with a blower, to carry away the heat of the molten type metal and allow the cast slugs to solidify quickly.

[19] When casting is complete, the plunger is drawn upward, pulling the metal back down the throat from the mouthpiece.

[22] The most significant innovation in the linotype machine was that it automated the distribution step; i.e., returning the matrices and space bands back to the correct place in their respective magazines.

After casting is completed, the matrices are pushed to the second elevator which raises them to the distributor at the top of the magazine.

("Pi" in this case refers to an obscure printer's term relating to loose or spilled type.)

Instead, it travels all the way to the end and into the flexible metal tube called the pi chute and is then lined up in the sorts stacker, available for further use.