Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

[3] This tandem technique can be used to analyze biochemical, organic, and inorganic compounds commonly found in complex samples of environmental and biological origin.

Therefore, LC–MS may be applied in a wide range of sectors including biotechnology, environment monitoring, food processing, and pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and cosmetic industries.

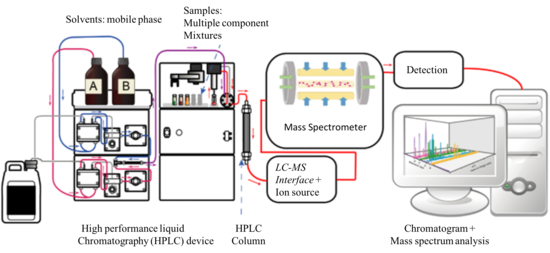

[6] In addition to the liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry devices, an LC–MS system contains an interface that efficiently transfers the separated components from the LC column into the MS ion source.

Gas chromatography (GC)–MS was originally introduced in 1952, when A. T. James and A. J. P. Martin were trying to develop tandem separation – mass analysis techniques.

Victor Talrose and his collaborators in Russia started the development of LC–MS in the late 1960s,[10][11] when they first used capillaries to connect an LC column to an EI source.

This pioneer interface for LC–MS had the same analysis capabilities of GC-MS and was limited to rather volatile analytes and non-polar compounds with low molecular mass (below 400 Da).

Rapidly, it was realized that the analysis of complex mixtures would require the development of a fully automated on-line coupling solution in LC–MS.

[8] The key to the success and widespread adoption of LC–MS as a routine analytical tool lies in the interface and ion source between the liquid-based LC and the vacuum-base MS.

After the liquid phase was removed, the belt passed over a heater which flash desorbed the analytes into the MS ion source.

[8] MBI was successfully used for LC–MS applications between 1978 and 1990 because it allowed coupling of LC to MS devices using EI, CI, and fast-atom bombardment (FAB) ion sources.

MBI interfaces for LC–MS allowed MS to be widely applied in the analysis of drugs, pesticides, steroids, alkaloids, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

To use this interface, it was necessary to split the flow coming out of the LC column because only a small portion of the effluent (10 to 50 μl/min out of 1 ml/min) could be introduced into the source without raising the vacuum pressure of the MS system too high.

Commercialized by Hewlett Packard, and later by VG and Extrel, it enjoyed moderate success, but has been largely supplanted by the atmospheric pressure interfaces such as electrospray and APCI which provide a broader range of compound coverage and applications.

The LC effluent passed through the heated probe and emerged as a jet of vapor and small droplets flowing into the desolvation chamber at low pressure.

For stable operation, the FAB based interfaces were able to handle liquid flow rates of only 1–15 μl and were also restricted to microbore and capillary columns.

In order to be used in FAB MS ionization sources, the analytes of interest had to be mixed with a matrix (e.g., glycerol) that could be added before or after the separation in the LC column.

In common applications, the mobile phase is a mixture of water and other polar solvents (e.g., methanol, isopropanol, and acetonitrile), and the stationary matrix is prepared by attaching long-chain alkyl groups (e.g., n-octadecyl or C18) to the external and internal surfaces of irregularly or spherically shaped 5 μm diameter porous silica particles.

[5] In HPLC, typically 20 μl of the sample of interest are injected into the mobile phase stream delivered by a high pressure pump.

These columns have smaller internal diameters, allow for a more efficient separation, and handle liquid flows under 1 ml/min (the conventional flow-rate).

This LC variant uses columns packed with smaller silica particles (~1.7 μm diameter) and requires higher operating pressures in the range of 310000 to 775000 torr (6000 to 15000 psi, 400 to 1034 bar).

Although there are many different kinds of mass spectrometers, all of them make use of electric or magnetic fields to manipulate the motion of ions produced from an analyte of interest and determine their m/z.

[21][22] A new approach still under development called direct-EI LC–MS interface, couples a nano HPLC system and an electron ionization equipped mass spectrometer.

In some sources, rapid droplet evaporation and thus maximum ion emission is achieved by mixing an additional stream of hot gas with the spray plume in front of the vacuum entrance.

These methods of increasing droplet evaporation now allow the use of liquid flow rates of 1 - 2 mL/min to be used while still achieving efficient ionisation[26] and high sensitivity.

[8] The APCI ion source/ interface can be used to analyze small, neutral, relatively non-polar, and thermally stable molecules (e.g., steroids, lipids, and fat soluble vitamins).

[8] The coupling of MS with LC systems is attractive because liquid chromatography can separate delicate and complex natural mixtures, which chemical composition needs to be well established (e.g., biological fluids, environmental samples, and drugs).

MS analyzers are useful in these studies because of their shorter analysis time, and higher sensitivity and specificity compared to UV detectors commonly attached to HPLC systems.

Examples are the recent discovery and validation of peptide biomarkers for four major bacterial respiratory tract pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, Moraxella catarrhalis; Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae) and the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

[37] Another example of LC–MS in plant metabolomics is the efficient separation and identification of glucose, sucrose, raffinose, stachyose, and verbascose from leaf extracts of Arabidopsis thaliana.

These features speed up the process of generating, testing, and validating a discovery starting from a vast array of products with potential application.