Lithuanization

[citation needed] A large part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania remained Ruthenian[citation needed]; due to religious, linguistic and cultural dissimilarity, there was less assimilation between the ruling nobility of the pagan Lithuanians and the conquered Orthodox East Slavs.

After the military and diplomatic expansion of the duchy into Ruthenian (Kievan Rus') lands, local leaders retained autonomy which limited the amalgamation of cultures.

[11][12] Around the time of Lithuanian independence, the country began moving toward the cultural and linguistic assimilation of large groups of non-Lithuanian citizens (primarily Poles and Germans).

[14] After World War I, the Council of Lithuania (the government's legislative branch) was expanded to include Jewish and Belarusian representatives.

[19] As Lithuania established its independence and its nationalistic attitudes strengthened, the state sought to increase the use of Lithuanian in public life.

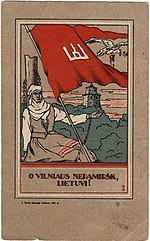

[29] Another target group for discrimination was the Poles; anti-Polish sentiment had appeared primarily due to the Polish occupation of Lithuania's capital Vilnius in 1920.

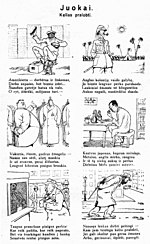

[30] Eugeniusz Romer (1871–1943) noted that the Lithuanian National Revival was positive in some respects, he described some excesses, which he found often to be funny, although aggressive towards Poles and Polish culture.

[citation needed] During the interwar, discussions started about returning to native Lithuanian surnames, as opposed to Germanization and Slavicisation (which included both Russification and Polonization).

[34] In modern Lithuania, which has been independent since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Lithuanization is not an official state policy.

[38] Lithuanization promoted the cooperation of Polish and Russian minorities, who support the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania.

According to the EU's Advisory Committee, this violates Lithuania's obligations under Article 11 (3) of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

[45] In 2014, Šalčininkai District Municipality administrative director Boleslav Daškevič was fined about €12,500 for failing to execute a court ruling to remove Polish traffic signs.