Green and golden bell frog

Its numbers have continued to fall and are threatened by habitat loss and degradation, pollution, introduced species, and parasites and pathogens, including the chytrid Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis.

The common name, "green and golden bell frog", was first adopted by Harold Cogger in his 1975 book Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia.

It has a pointy snout, long legs, and almost complete toe webbing; the tympanum is large and distinct; and the overall body shape is similar to many Rana species.

The bone and cartilage structural formations of the green and golden bell frog are closest to those of species in the family Hylidae; it was therefore reclassified.

Albumin immunological distance data suggest no differentiation between the two, and the green and golden bell frog evolutionally separated from the other two species about 1.1 million years ago.

Before its decline in population, its distribution ranged from Brunswick Heads, in northern New South Wales, to East Gippsland, in Victoria,[7] and west to Bathurst, Tumut and the Australian Capital Territory.

The bell frog's current distribution now ranges from Byron Bay, in northern New South Wales, to East Gippsland, in Victoria; populations mostly occur along the coast.

Metamorphlings are divided in roughly equal numbers between males and females, while juvenile frogs are observed less often than their mature counterparts, although scientists are not sure whether this is due to lower abundance or increased reclusiveness.

It is generally associated with coastal swamps, wetlands, marshes, dams, ditches, small rivers, woodlands, and forests, but populations have also been found at former industrial sites (for instance, the Brickpit).

[25] It is most typically found in short-lived freshwater ponds that are still, shallow, unshaded, and unpolluted, and it tends to avoid waters that contain predatory fish, whether native or introduced.

[1][27] It prefers waterways with a substrate of sand, rock, or clay,[20] and can tolerate a wide range of water turbidities, pH and oxygen levels, and temperatures, although these can hamper physical growth.

The green and golden bell frog also favours areas with the greatest habitat complexity, and as such, this is a core component of habitat-based strategies to protect the species.

In cold conditions, the frogs are thought to hibernate, based on observations of some being uncovered in a "torpid" state, but this has yet to be proven with rigorous physiological studies.

[20] On the other hand, salinity levels of at least 1–2 ppt can be beneficial to the green and golden bell frog because this kills pathogens such as the chytrid fungus.

[26][32] The voracious adults have very broad diets, including insects such as crickets, larvae, mosquito wrigglers, dragonflies, earthworms, cockroaches, flies, and grasshoppers.

Smaller, still-growing green and golden bell frogs tend to hunt small, especially flying, insects, often jumping to catch their prey.

[27] Natural predators include wading birds, such as reef egrets, white-faced herons, white ibises and swamp harriers.

[24] The green and golden bell frog breeds in the warmer months from October to March, although some cases have been recorded earlier at the end of winter.

[36] Males appear to reach maturity at around 45–50 mm, at between 9 and 12 months, and at this size begin to develop a grey to brownish yellow wash beneath the chin.

Given the large number of eggs that hatch per female and given the scarcity of mature frogs, tadpole survival rates are believed to be very low.

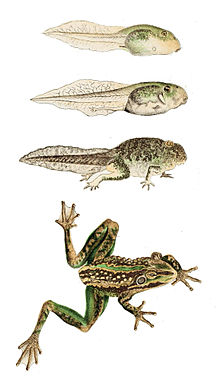

[26] The tadpoles of the green and golden bell frog are large, reaching 80 mm (3.1 in) in length,[17] but size varies greatly and most are much shorter.

[37] Recently metamorphosed frogs have been observed to rapidly leave the breeding site, especially when foraging habitat is nearby, and less so if food is not available away from the area.

[41] Metamorphs weigh about 2 g, while the largest adults can reach 50 g. Individual frogs can vary substantially in body weight due to changes in the amount of stored fat, recent eating, and egg formation.

[42] Many factors are thought to be responsible for the dramatic decline of this species in Australia, including habitat fragmentation, erosion and sedimentation of soil, insecticides and fertilisers contaminating water systems,[43] the introduction of predatory fish, and alteration of drainage regimes.

[12] Population declines are closely related to the introduction of the eastern mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki),[12] a species native to North America that was introduced to control mosquito larvae.

[45][46] Other factors thought to affect this species include predation by introduced mammals, such as cats and foxes, changes to water quality at breeding sites,[12] herbicide use,[43] and loss of habitat through the destruction of wetlands.

This has led to proposals for frog populations to be mixed by human intervention in an attempt to reduce negative genetic effects and boost survival rates.

Global warming is not thought to be a credible cause, as the extremities of the frog's range have not changed, while declines in population have occurred in both dry and wetter areas.

[53] As green and golden bell frogs are mostly observed in environments disturbed by humans, targeted environmental interference is seen as a possible means of enhancing habitats.

Between 1998 and 2004, tadpoles were released into specially designed ponds and dams on Long Reef Golf Course at Collaroy in northern Sydney, with little success.