Little Annie Fanny

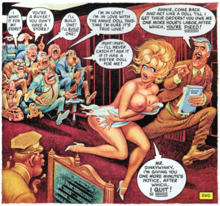

Annie Fanny, the title character, is a statuesque, buxom young blonde woman who innocently finds herself nude in every episode.

Critical reaction was mixed, with most praising the elaborate, fully painted comic, but some dismissing it as falling short of Kurtzman's full potential.

[1] Hefner offered Kurtzman an opportunity to conceive a new humor magazine for his enterprise, which the cartoonist accepted when he left Mad in 1956 in an ownership dispute.

Kurtzman then worked out the story's composition, pacing, and action in thumbnail drawings and pencil roughs of each page of the comic, followed by larger, more-detailed layouts on translucent vellum specifying lighting, color, and speech balloon placement.

Beginning with a white illustration board, Elder explained he would "pile on" his oil paint, light colors over dark, then apply tempera, then layer several watercolor washes to give Annie luminous tones.

"[19] The work was labor-intensive and deadlines were often difficult to meet, so other artists, including Russ Heath, Arnold Roth, Jack Davis, Al Jaffee, Frank Frazetta, and Paul Coker, were occasionally enlisted to help finish the art.

[20] Jaffee, a childhood friend of Elder, said about the experience: "Little Annie Fannie was the most unique, lavishly produced cartoon cum illustration feature ever.

[25] The authors of Icons of the American Comic Book say Annie "glides through a changing world with an untiring optimism" with a "good-natured lack of desire".

Ralphie Towzer, Annie's nerdy-but-hip do-gooder boyfriend, has the look of Goodman Beaver (with playwright Arthur Miller's eyeglasses and pipe) and the temperament of a strait-laced, chastising prude.

Other supporting characters include ad man Benton Battbarton (whose name is taken from the advertising agencies Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn and Benton & Bowles), Battbarton's rival Huck Buxton (modeled on gap-toothed British actor Terry-Thomas), Duncan Fyfe Hepplewhite (an art plagiarist), and Freddie Flink (who resembles comic actor Fred Gwynne from Car 54, Where Are You?).

During the strip's first decade, when it ran up to eleven times per year, Annie meets caricatures of the Beatles (who lust for Annie), Sean Connery (playing "James Bomb"), reclusive Catcher in the Rye author J. D. Salinger (as "Salinger Fiengold"), NFL champions Green Bay Packers (as the "Greenback Busters"), and Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, and Sonny & Cher on the "Hoopadedoo Show" (Hullabaloo show).

Background caricatures include Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, prissy-but-powerful J. Edgar Hoover, unisex fashion designer Rudi Gernreich, and the "Put a Tiger in Your Tank" ad campaign of Humble Oil.

[29] During the 1970s, when the strip ran three to five times per year, Annie sees violent films such as A Clockwork Orange and The French Connection and meets sex novelist Philip Roth, consumer advocate Ralph Nader, chess champion Bobby Fischer, and shock rocker Alice Cooper.

Background "eye pops" include Hollywood heavy Charles Bronson, Laugh-In's Arte Johnson, the Avis TV commercial's O. J. Simpson, and Star Wars' C-3PO.

"[23] According to comics commentators Randy Duncan and Matthew J. Smith, the series "reads today as an amusing look at the evolving mores of the sexual revolution".

Noting that Kurtzman was financially strapped before making his living for twenty-six years from Playboy, historian Paul Buhle wrote: "The strip had many brilliant early moments, but went downhill as the writer and artist bent to editor Hugh Hefner's demands for as much titillation as possible.

[38] Monty Python's Terry Gilliam, the former assistant editor of Help!, said that Little Annie Fanny was not as sharp as Kurtzman's earlier work: "technically brilliant but ... slightly compromised.

[32] Kitchen placed the onus on Kurtzman's employer Hefner, who "was often a punctilious taskmaster with a heavy red pen who often had very different ideas about what was funny or satiric" and insisted that each strip "had to include Annie disrobing".

"[40] Duncan and Smith also agreed, and wrote that "humor sometimes mixes awkwardly with the loaded topics of the era, and some have found Annie's lack of character development and the requisite sexual hijinks an impediment to taking her seriously."

"[41] American cartoonist Budd Root cited Little Annie Fanny as one of the inspirations for his independent comic book series Cavewoman.