Liturgy (ancient Greece)

The liturgy (Greek: λειτουργία or λῃτουργία, leitourgia, from λαός / Laos, "the people" and the root ἔργο / ergon, "work" [1]) was in ancient Greece a public service established by the city-state whereby its richest members (whether citizens or resident aliens), more or less voluntarily, financed the State with their personal wealth.

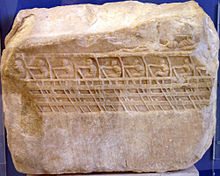

[3] The liturgical system dates back to the early days of Athenian democracy, and included the constitutional duty of trierarchy, which gradually fell into disuse by the end of the 4th century BC,[4] eclipsed by the development of euergetism in the Hellenistic period.

The liturgy was the preferred mode of financing of the Greek city, to the extent that it allowed them to easily associate each public expense with a ready source of revenue.

[6] Those associated with the liturgical or agonistic calendar (related to sporting and religious events) are mainly the gymnasiarchia (γυμνασιαρχία), that is to say, the management and financing of the gymnasium, and the choregia (χορηγία), the maintenance of the choir members at the theater for dramatic competitions.

The hestiasis (ἑστίασις) was to fund the public dinner of the tribe to which the liturgist belonged;[7] the architheoria (ἀρχιθεωρία) to lead delegations to the four sacred Panhellenic Games;,[8][9] the arrhephoria (ἀρρηφορία) to cover the cost of the arrhephoroi, four girls of Athenian high society who brought the peplos to the Athena Parthenos, offered her cakes and dedicated white dresses adorned with gold,[10] amongst others.

The trierarch was also to assume, under the direction of the strategos, the command of the ship, unless he choose to pay a concession and left the fighting to a specialist in which case the office was purely financial.

In fact, establishing a threshold requirement would have made liturgical expense mandatory instead of voluntary, and caused the city difficulty in the event of widespread impoverishment of its individual members.

[22] However, thresholds of informal wealth beyond which an individual could not shirk his duty were regularly raised in court pleadings: it is clear that in Athens in the 4th century BC a patrimony of 10 talents[23] necessarily makes its holder a member of the "liturgical class".

The size of the "liturgical class" can be estimated for classical Athens as a range between 300 [27] and 1200 individuals,[28] or as high as 1500–2000 if we take care not to confuse the number of people required to administer the system and the contingent of those who actually took up the liturgy.

[32] The least expensive was the eutaxia (εὐταξία), known by a single mention,[32] which cost only 50 drachmas; its nature is unknown - it may be related to the Amphiareia Games at Oropos[33] and probably did not last a long time.

[37] The great expense of these liturgies explains the appearance of the syntrierarchy, which placed the financial burden on two individuals,[38] and Periander's establishment in 357 of 20 symmoriai composed of 60 taxpayers each.

[42] Assuming a yield of 8% from the land they held, the poorest liturgists, who had a net worth of ten talents (as Demosthenes did in 360 /59), were forced to devote the greater part of a year's revenue to the trierarchy.

[4] In addition, citizens or resident aliens might be granted an honorary exemption, for services rendered to the city (ἀτέλεια / atéleia),[49] but "not for trierarchy, nor contributions to the war "[51] (proeisphora).

[69] The easiest way to avoid the burden of the liturgy was to conceal one's wealth, which was very easy in Athens: information about property was fragmented, as there was no register of all the land belonging to an individual.

[73] The concealment of assets by the wealthy appears to have been widespread, so that a client of Lysias boasts that his father would never resort to it: "when he might well have put his fortune away out of sight and refused to help you, he preferred that you should know of it, in order that, even if he chose to be a bad citizen, he could not, but must make the required contributions and perform the liturgies.

[75] The accusation of evasion of public charges was very common in judicial speeches: litigants clearly played upon the prejudices of the jury, that all the rich preferred not to pay, if they could get away with it.

[76] The honorific inscriptions available show that, regularly, some wealthy citizens or resident aliens "had eagerly discharged them [their public services] all",[77] by volunteering (ἐθελοντής), as Demosthenes had in 349 BC.,[77] for sometimes very expensive liturgies which they could escape.

[78] This same litigant even adds a bit further on: "this is indeed how I treat the city: in my private life I'm thrifty, but in public office I gladly pay, and I am proud not of the property I have left, but of the spending that I made for you. "

The liturgy was indeed an opportunity "with his wealth, simultaneously to affirm his devotion to the city, and to claim his place among the most important people" ("avec ses biens, à la fois d'affirmer son dévouement envers la cité et de revendiquer sa place parmi les gens qui comptent"),[83] to better enforce the liturgist's political position and take his place - or to that to which he aspires - in the city: besides devoting his fortune to the public good, paying "his property and his person" [84] the liturgist distinguishes himself from the vulgem pecus and gets the people of the city to confirm the legitimacy of his dominant social position,[81] which would be especially significant when the liturgist was subsequently involved in a trial or election to the magistracy.

This was compensation awarded to citizens serving in certain public functions, to counterbalance the ties of patronage created by the magnificence with which Pericles' rival, Cimon, performed his liturgical responsibilities.

For the first time, the idea became current that personal wealth is not primarily intended to serve the city, but one's own good, even though expressed "discreetly, insensibly, without the rich admitting it openly".

[90][91] This exemplified the development of a certain defiance of liturgical responsibilities in the first half of the 4th century BC., a trend reinforced by the military and financial efforts agreed to at the time of the Corinthian War (395–386).

Therefore, the need for the Athenian state to find new sources of funding, could only be achieved through better management of public assets (the policy of Eubulus, then Lycurgus), and by increased financial pressure on the richest.

The complaints of the wealthy have an undeniable dimension of ideological and political hostility to the common people (demos): Xenophon[94] and Isocrates[95] emphasize that "the liturgy is a weapon in the hands of the poor".

[96] However, the less fortunate liturgists, those whose social status was closest to the average citizen, were quick to denounce the lack of civic-mindedness of the rich, who tended to be more supportive of the reactionary Oligarchy than of democracy.

[85] In fact, most of the complaints related to those liturgies perceived as lacking social value (proeisphora, syntriérarchie), or which involved direct financial contributions (such as the eisphora).

The exact chronology of this phenomenon is problematic, however: the passage from adherence to liturgical responsibilities, to their rejection by the individuals obligated to perform them, is difficult to date precisely.

The liturgists' increasing desire for a rapid return on investment (which led to favorable treatment by the juries in trials in which they were involved), caused ordinary citizens to re-evaluate the utility of each liturgy.

Lycurgus said in 330: However, there are those among them who, giving up the attempt to convince you with arguments, seek your pardon by pleading their liturgies: Nothing makes me angrier, on this account, than the idea that expenses they sought for their own glory, should become a claim to public favor.

No-one earns a right to your gratitude, simply for having fed the horses, or paid for lavish choregies, or other largesse of this kind; on such occasions, one obtains the crown of victory for himself alone, without the least benefit to others.