Lloyd's of London

[2] Having survived multiple scandals and significant challenges through the second half of the 20th century, most notably the asbestosis losses which engulfed the market, Lloyd's today promotes its strong financial "chain of security" available to promptly pay all valid claims.

This report advocated the widening of membership to non-market participants, including non-British subjects and then women, and the reduction of the onerous capitalisation requirements (thus creating a minor investor known as a "mini-Name").

Den-Har had suspected Mafia links and many of the risks written were rigged: typically dilapidated buildings in slums such as New York's south Bronx, which soon burned down after being insured for large sums.

The Names (few in number for such large losses) took legal action and ultimately paid only £6.25m of c. £15m of Den-Har claims under the 1976 year, leaving the Corporation of Lloyd's to pay the remainder.

[2] Problems also developed out of the Oakley Vaughan agency run by brothers Edward and Charles St George, which had written far more business than its capacity allowed in order to invest premium to take advantage of high interest rates.

[19] Arising simultaneously with these developments were wider issues: first, in the US, an ever-widening interpretation by the courts of insurance coverage in relation to workers' compensation for asbestosis-related claims, which created a huge hole in Lloyd's loss-payment reserves, which was initially not recognised and then not acknowledged.

Immediately after the passing of the 1982 act, evidence came to light and internal disciplinary proceedings were commenced against a number of underwriters who had allegedly siphoned money from their syndicates to their own accounts.

[citation needed] Lioncover's PCW liabilities were reinsured as part of the Equitas arrangement in the late 1990s and transferred to National Indemnity Company in two stages in 2007 and 2009.

Lloyd's also faced action from Names on C. J. Warrilow's syndicate 553, which had chronically exceeded its underwriting capacity in the early 1980s and failed to adequately reinsure the huge quantity of risks it was taking on.

The rig's operator, Occidental Petroleum, bought a direct insurance policy from Lloyd's underwriters, who then passed part of their shares of the risk on to other syndicates via reinsurance.

Unexpectedly large legal awards in US courts for punitive damages led to substantial claims on asbestos, pollution and health hazard (APH) policies, some dating as far back as the 1940s.

In the case of Lloyd's, this resulted in the bankruptcy of thousands of individual investors who indemnified general liability policies written from the 1940s to the mid-1970s for companies with exposure to asbestosis claims.

Therefore, the amounts of money transferred from earlier years by successive RITC premiums to cover these losses were grossly insufficient, and the current members had to pay the shortfall.

As a result, a great many Names whose syndicates wrote long-tail liability at Lloyd's faced significant financial loss or ruin by the late 1980s to mid-1990s.

When the huge extent of asbestosis losses came to light in the early 1990s, for the first time in Lloyd's history large numbers of members either were unable to pay the claims or refused, many alleging that they were the victims of fraud, misrepresentation, and/or negligence.

The opaque system of accounting at Lloyd's made it difficult, if not impossible, for many Names to understand the extent of the liability that they personally and their syndicates had subscribed to.

Under the chairmanship of Sir David Rowland and chief executive Peter Middleton, an ambitious plan entitled "Reconstruction and Renewal" (R&R) was produced in 1995, with proposals for separating the ongoing Lloyd's from its past losses.

Liabilities for all pre-1993 business (other than life assurance) were to be compulsorily transferred (by RITC) into a special vehicle named Equitas (which would require the approval of the UK's Department of Trade and Industry) at a cost of around $21bn.

[25] Many Names faced large bills, but the plan also provided for a settlement of their disputes, a tax on recent profits, and the write-off of nearly $5bn owed in the form of "debt credits", skewed towards those with the worst losses.

The plan was debated at length, modified, and eventually strongly supported by the Association of Lloyd's Members (ALM) and most leaders of Names' action groups.

On each occasion the allegation that there had been a policy to recruit to dilute was dismissed and Names were urged to settle; however, at first instance the judge described the Names as "the innocent victims [...] of staggering incompetence" and the appeal court found that representations that Lloyd's had a rigorous auditing system were false and strongly hinted that one of Lloyd's main witnesses, former chairman Murray Lawrence, had lied in his testimony.

Lloyd's rebounded and started to thrive again after the catastrophic losses arising out of the World Trade Center attack, but it faced increased competition from newly-created companies in Bermuda and other markets.

The Franchise Board lays down guidelines for all syndicates and operates a business planning and monitoring process to safeguard high standards of underwriting and risk management, thereby improving sustainable profitability and enhancing the financial strength of the market.

An integrated Lloyd's vehicle (ILV) is a group of companies that combines a corporate member, a managing agent, and a syndicate under common ownership.

The third link consists largely of the Lloyd's Central Fund, which contains mutual assets held by the Corporation which are available, subject to Council approval as required, to meet any member's liabilities.

[40] In 2001 the calendar year result was a 140 per cent combined ratio, driven largely by claims arising out of the World Trade Center attack, reserve increases for prior-year liabilities and deteriorating pricing levels.

[66] Lloyd's also has a unique niche in unusual, specialist business such as kidnap and ransom, fine art, specie, aviation, war, satellites, personal accident, bloodstock, and other insurances.

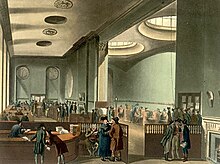

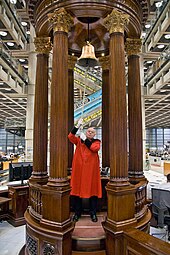

[75] In the main Underwriting Room of Lloyd's stands the Lutine bell, salvaged in 1858, which was rung when the fate of a ship "overdue" at its destination port became known.

Nowadays it is only rung for ceremonial purposes, such as the visit of a distinguished guest, or for the annual Remembrance Day service and anniversaries of major world events.

Brokers and underwriters are still normally held to, and apparently prefer, a more formal style of attire than many nearby City of London banks and financial institutions.