Lockheed A-12

The CIA's representatives initially favored Convair's design for its smaller radar cross-section, but the A-12's specifications were slightly better and its projected cost was much lower.

Convair's work on the B-58 had been plagued with delays and cost overruns, whereas Lockheed had produced the U-2 on time and under budget.

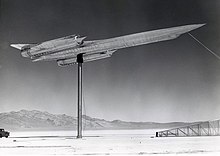

It was the precursor to the twin-seat U.S. Air Force YF-12 prototype interceptor, M-21 launcher for the D-21 drone, and the SR-71 Blackbird, a slightly longer variant able to carry a heavier fuel and camera load.

[5] With the failure of the CIA's Project Rainbow to reduce the radar cross-section (RCS) of the U-2, preliminary work began inside Lockheed in late 1957 to develop a follow-on aircraft to overfly the Soviet Union.

Designer Kelly Johnson said, "In April 1958 I recall having long discussions with [CIA Deputy Director for Plans] Richard M. Bissell Jr. over the subject of whether there should be a follow-on to the U-2 aircraft.

[9] In his book Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed, Ben Rich stated, "Our supplier, Titanium Metals Corporation, had only limited reserves of the precious alloy, so the CIA conducted a worldwide search and using third parties and dummy companies, managed to unobtrusively purchase the base metal from one of the world's leading exporters – the Soviet Union.

The solution was found by machining only small "fillets" of the material with the required shape and then gluing them onto the underlying framework which was more linear.

A good example is on the wing: the underlying framework of spars and stringers formed a grid, leaving triangular notches along the leading edge that were filled with fillets.

[13][14][15] To further reduce the detectability of the aircraft's afterburner plumes a special cesium additive nicknamed "panther piss" was added to the fuel.

[16][17] After development and production at Skunk Works, in Burbank, California, the first A-12 was transferred to Groom Lake test facility (Area 51).

[20] In 1962, the first five A-12s were initially flown with Pratt & Whitney J75 engines capable of 17,000 lbf (76 kN)[citation needed] thrust each, enabling the J75-equipped A-12s to obtain speeds of approximately Mach 2.0.

[23] Collins safely ejected and was wearing a standard flight suit, avoiding unwanted questions from the truck driver who picked him up.

Each was also paid $25,000 (equivalent to $249,000 in 2023) in cash to do so; the project often used such cash payments to avoid outside inquiries into its operations (the project received ample funding for many objectives: contracted security guards were paid $1,000 (equivalent to $10,000 in 2023) monthly with free housing on base, and chefs from Las Vegas were available 24 hours a day for steak, Maine lobster, or other requests).

On 9 July 1964, "Article 133" crashed while making its final approach to the runway when a pitch-control servo device froze at an altitude of 500 ft (150 m) and airspeed of 200 knots (230 mph; 370 km/h) causing it to begin a smooth steady roll to the left.

[28][2] On 28 December 1965, the third A-12 was lost when "Article 126" crashed 30 seconds after takeoff when a series of violent yawing and pitching actions was followed very rapidly with the aircraft becoming uncontrollable.

Mel Vojvodich was scheduled to take aircraft number 126 on a performance check flight which included a rendezvous beacon test with a KC-135 tanker and managed to eject safely 150 to 200 ft (46 to 61 m) above the ground.

A post-crash investigation revealed that the primary cause of the accident was a maintenance error; a flight-line electrician had mistakenly swapped the connections of the wiring harnesses linking the yaw- and pitch-rate gyroscopes of the Stability Augmentation System to the control-surface servos, meaning that control inputs commanding pitch changes counterintuitively caused the aircraft to yaw and control inputs commanding left or right yaw instead changed the aircraft's pitch angle.

The investigation criticised the electrician's negligence, but also noted as contributory causes failures in the supervision of maintenance activity and the fact that the aircraft's design allowed for the swapped connection in the first place.

The first fatality of the Oxcart program occurred on 5 January 1967, when "Article 125" crashed, killing CIA pilot Walter Ray when the aircraft ran out of fuel while on its descent to the test site.

After a U-2 was shot down in May 1960, the Soviet Union was considered too dangerous to overfly except in an emergency (and overflights were no longer necessary,[33] thanks to reconnaissance satellites) and, although crews trained for flights over Cuba, U-2s continued to be adequate there.

[35] Mel Vojvodich flew the first Black Shield operation, over North Vietnam, photographing surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites, flying at 80,000 ft (24,000 m), and at about Mach 3.1.

Later an Air Force Center in Japan carried out the processing in order to place the photointelligence in the hands of American commanders in Vietnam within 24 hours of completion of a mission.

[2] There were a number of reasons leading to the retirement of the A-12, but one major concern was the growing sophistication of Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites that it had to contend with over mission routes.

Good quality photography was obtained of Khe Sanh and the Laos, Cambodia, and South Vietnamese border areas.

The aim was to discover whether the North Koreans were preparing any large scale hostile move following this incident and to actually find where the Pueblo was hidden.

By 1965, moreover, the photoreconnaissance satellite programs had progressed to the point that crewed flights over the Soviet Union were unnecessary to collect strategic intelligence.

Lockheed convinced the U.S. Air Force that an aircraft based on the A-12 would provide a less costly alternative to the recently canceled North American Aviation XF-108, since much of the design and development work on the YF-12 had already been done and paid for.

[69] The D-21 was autonomous; after launch, it would fly over the target, travel to a predetermined rendezvous point, eject its data package, and self-destruct.

The crew ejected, but LCO Ray Torrick drowned when his flight suit filled with water after landing in the ocean.

[72][73] Six of the 15 A-12s were lost in accidents, with the loss of two pilots and an engineer: Data from A-12 Utility Flight Manual[80]General characteristics Performance Related development Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era