London Necropolis railway station

[4] Despite the rapid growth in population, the amount of land set aside for use as graveyards remained unchanged at approximately 300 acres (0.5 sq mi; 1.2 km2),[2] spread across around 200 small sites.

[6] Decaying corpses contaminated the water supply, and the city suffered regular epidemics of cholera, smallpox, measles and typhoid.

[7] A royal commission established in 1842 to investigate the problem concluded that London's burial grounds had become so overcrowded that it was impossible to dig a new grave without cutting through an existing one.

[15][note 1] At this distance, the land would be far beyond the maximum anticipated size of the city's growth, greatly reducing any potential hazards.

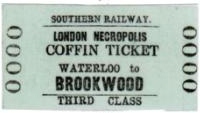

[17] On 30 June 1852 the promoters of the Brookwood scheme were given parliamentary consent to proceed, and the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company (LNC) was formed.

[26][27] Despite objections from local residents concerned about the effects of potentially large numbers of dead bodies being stored in a largely residential area,[28] in March 1854 the LNC settled on a single terminus in Waterloo and purchased a plot of land between Westminster Bridge Road and York Street (now Leake Street) for the site.

[33] Although the original terminus did not have its own chapel, on some occasions mourners would not be able or willing to make the journey to a ceremony at Brookwood but for personal or religious reasons were unable to hold the funeral service in a London church.

[37] One of the more notable funerals to be held at the terminus was that of Friedrich Engels, co-creator (with Karl Marx) of modern communism, who died in London on 5 August 1895.

[42] The LNC never built their own crematorium, although a columbarium (building for the storage of cremation ashes) was added to Brookwood Cemetery in 1910.

[38] For extremely large funerals such as those of major public figures, the LSWR would provide additional trains from Waterloo to Brookwood station on the main line to meet the demand.

[46] At this time the LSWR also leased a small plot of land west of the Westminster Bridge Road entrance to serve as the site of new offices for the LNC, designed by Cyril Bazett Tubbs.

Urban growth in the area of what is now south west London, through which trains from Waterloo ran, led to congestion at the station, only slightly alleviated by the LSWR's 1877 takeover of the western LNC track.

In the 1890s the situation became untenable, and the LSWR began to investigate the possibility of repositioning the LNC station to permit the expansion of the main line terminus.

This in turn led to the location identified for the two new rail lines, at a right angle to the central strip (i.e. parallel to the entrance).

[50] On 23 February Major J. W. Pringle of the Board of Trade inspected the new building and expressed concerns over the safety of the arrangements for trains entering the station from the main line, which entailed crossing the LSWR's multiple tracks.

[54] First class mourners entered through the driveway under the office building which turned sharply left to run beneath a glass canopy parallel to Westminster Bridge Road; this stretch was faced with glazed white brick and lined with palm and bay trees.

The driveway ran past mortuaries and storerooms to the lifts and stairs to the platforms, and also to a secondary entrance on Newnham Terrace (off Hercules Road).

[55] This upper level housed a sumptuous oak-panelled chapelle ardente, intended for mourners unable to make the journey to Brookwood to pay their respects to the deceased.

The funeral of Indian businessman Sir Nowroji Saklatwala on 25 July 1938 saw 155 mourners travelling first class on a dedicated LNC train.

[63] Brookwood was one of the few cemeteries to permit burials on Sundays, which made it a popular choice with the poor as it allowed people to attend funerals without the need to take a day off work.

[60] (After the relocation to the new London terminus in 1902, some funeral services would be held in the Chapelle Ardente at platform level, for those cases where mourners were unable to make the journey to Brookwood.

[57] During the night of 16–17 April 1941, in one of the last major air raids on London,[note 8] bombs repeatedly fell on the Waterloo area, and the LNC's good fortune in avoiding damage to their facilities finally ran out.

[72] At 10.30 pm multiple incendiary devices and high explosive bombs struck the central section of the terminus building.

[72][note 10] The last recorded funeral carried on the London Necropolis Railway was that of Chelsea Pensioner Edward Irish (1868–1941), buried on 11 April 1941.

[75][76] The LNC attempted to negotiate a deal by which bona fide mourners could still travel cheaply to the cemetery on the 11.57 am service to Brookwood (the SR service closest to the LNC's traditional departure time), but the SR management (themselves under severe financial pressure owing to wartime constraints and damage) refused to entertain any compromise.

[77] In September 1945, following the end of hostilities, the directors of the LNC met to consider whether to rebuild the terminus and reopen the London Necropolis Railway.

[64] In the original proposal, Sir Richard Broun had calculated that over its first century of operations the cemetery would have seen around five million burials at a rate of 50,000 per year, the great majority of which would have utilised the railway.

[71] Before the outbreak of hostilities increased use of motorised road transport had damaged the profitability of the railway for both the LNC and the SR.[53] Faced with the costs of rebuilding the cemetery branch line, building a new London terminus and replacing the rolling stock damaged or destroyed in the air raid, the directors concluded that "past experience and present changed conditions made the running of the Necropolis private train obsolete".

[74] Although one of the LNC's hearse carriages had survived the bombing it is unlikely that this was ever used, and coffins were carried in the luggage space of the SR's coaches.

[53] Most of the site of the second station was sold by the LNC and built over with new office developments in the years following the end of the Second World War, but the office building on Westminster Bridge Road, over the former entrance to the station driveway, remains relatively unaltered externally although the words "London Necropolis" carved into the stone above the driveway have been covered.