Lonely runner conjecture

In number theory, specifically the study of Diophantine approximation, the lonely runner conjecture is a conjecture about the long-term behavior of runners on a circular track.

runners on a track of unit length, with constant speeds all distinct from one another, will each be lonely at some time—at least

The conjecture was first posed in 1967 by German mathematician Jörg M. Wills, in purely number-theoretic terms, and independently in 1974 by T. W. Cusick; its illustrative and now-popular formulation dates to 1998.

The conjecture is known to be true for seven runners or fewer, but the general case remains unsolved.

Implications of the conjecture include solutions to view-obstruction problems and bounds on properties, related to chromatic numbers, of certain graphs.

runners on a circular track of unit length.

[2] In many formulations, including the original by Jörg M. Wills,[3][4] some simplifications are made.

of positive, distinct speeds, there exists some time

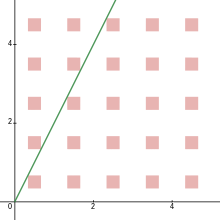

[6] Interpreted visually, if the runners are running counterclockwise, the middle term of the inequality is the distance from the origin to the

, ignoring rays lying in one of the coordinate hyperplanes.

[8] For example, placed in 2-dimensional space, squares any smaller than

or greater will obstruct every ray that is not parallel to an axis.

The conjecture generalizes this observation into any number of dimensions.

with separate methods, and because the smaller cases of the lonely runner conjecture are settled, the full theorem is proven.

For example, if the runner to be lonely is stationary and speeds

[c] Alternatively, this conclusion can be quickly derived from the Dirichlet approximation theorem.

Perarnau & Serra (2016) showed unconditionally for sufficiently large

Tao (2018) proved the current best known asymptotic result: for sufficiently large

[14] The conjecture has been proven under specific assumptions on the runners' speeds.

If the constant 22 is replaced with 33, then the conjecture holds true for

was computer-assisted, but all cases have since been proved with elementary methods.

[19] There exists an explicit infinite family of such sporadic cases.

[20] Kravitz (2021) formulated a sharper version of the conjecture that addresses near-equality cases.

Rifford (2022) addressed the question of the size of the time required for a runner to get lonely.

distinct and positive then the static runner is separated by a distance at least

A much stronger result exists for randomly chosen speeds: using the stationary-runner convention, if

runners with nonzero speeds are chosen uniformly at random from

In other words, runners with random speeds are likely at some point to be "very lonely"—nearly

[21] The full conjecture is true if "loneliness" is replaced with "almost aloneness", meaning at most one other runner is within

[22] The conjecture has been generalized to an analog in algebraic function fields.