Long QT syndrome

[4][5][8] Management may include avoiding strenuous exercise, getting sufficient potassium in the diet, the use of beta blockers, or an implantable cardiac defibrillator.

[6] For people with LQTS who survive cardiac arrest and remain untreated, the risk of death within 15 years is greater than 50%.

When symptoms occur, they are generally caused by abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias), most commonly a form of ventricular tachycardia called Torsades de pointes (TdP).

If the arrhythmia reverts to a normal rhythm spontaneously the affected person may experience lightheadedness (known as presyncope) or faint which may be preceded by a fluttering sensation in the chest.

[13] The arrhythmias that lead to faints and sudden death are more likely to occur in specific circumstances, in part determined by which genetic variant is present.

[15] Arrhythmias occur more commonly in drug-induced LQTS if the medication in question has been rapidly given intravenously, or if high concentrations of the drug are present in the person's blood.

[19] The risk of arrhythmias is also higher if the person receiving the drug has heart failure, is taking digitalis, or has recently been cardioverted from atrial fibrillation.

[19] Other risk factors for developing torsades de pointes among those with LQTS include female sex, increasing age, pre-existing cardiovascular disease, and abnormal liver or kidney function.

[21] The common thread linking these variants is that they affect one or more ion currents leading to prolongation of the ventricular action potential, thus lengthening the QT interval.

[22] The most common of these, accounting for 99% of cases, is Romano–Ward syndrome (genetically LQT1-6 and LQT9-16), an autosomal dominant form in which the electrical activity of the heart is affected without involving other organs.

[23] Other rare forms include Andersen–Tawil syndrome (LQT7) with features including a prolonged QT interval, periodic paralysis, and abnormalities of the face and skeleton; and Timothy syndrome (LQT8) in which a prolonged QT interval is associated with abnormalities in the structure of the heart and autism spectrum disorder.

[24] It is caused by variants in the KCNH2 gene (also known as hERG) on chromosome 7 which encodes the potassium channel that carries the rapid inward rectifier current IKr.

[24] This current contributes to the terminal repolarisation phase of the cardiac action potential, and therefore the length of the QT interval.

Similar to LQT3, these caveolin variants increase the late sustained sodium current, which impairs cellular repolarization.

[4] LQT7, also known as Andersen–Tawil syndrome, is characterised by a triad of features – in addition to a prolonged QT interval, those affected may experience intermittent weakness often occurring at times when blood potassium concentrations are low (hypokalaemic periodic paralysis), and characteristic facial and skeletal abnormalities such as a small lower jaw (micrognathia), low set ears, and fused or abnormally angled fingers and toes (syndactyly and clinodactyly).

Abnormalities of the structure of the heart are commonly seen including ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Drug-induced QT prolongation is often a result of treatment by antiarrhythmic drugs such as amiodarone and sotalol, antibiotics such as erythromycin, or antihistamines such as terfenadine.

[32] Other causes of acquired LQTS include abnormally low levels of potassium (hypokalaemia) or magnesium (hypomagnesaemia) within the blood.

The malnutrition seen in this condition can sometimes affect the blood concentration of salts such as potassium, potentially leading to acquired long QT syndrome, in turn causing sudden cardiac death.

The common theme is a prolongation of the cardiac action potential – the characteristic pattern of voltage changes across the cell membrane that occur with each heart beat.

[35] The early afterdepolarisations triggering arrhythmias in long QT syndrome tend to arise from the Purkinje fibres of the cardiac conduction system.

[35] Some research suggests that delayed afterdepolarisations, occurring after repolarisation has completed, may also play a role in long QT syndrome.

This allows the depolarising wavefront to bend around areas of block, potentially forming a complete loop and self-perpetuating.

The twisting pattern on the ECG can be explained by movement of the core of the re-entrant circuit in the form of a meandering spiral wave.

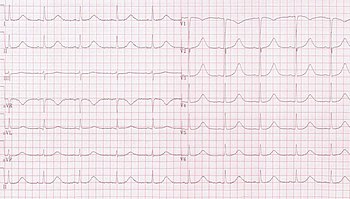

[23] The Schwartz score has been proposed as a method of combining clinical and ECG factors to assess how likely an individual is to have an inherited form of LQTS.

The European Society of Cardiology recommends that, with or without symptoms or other investigations, LQTS can be diagnosed if the corrected QT interval is longer than 480ms.

[4][5] Those diagnosed with LQTS are usually advised to avoid drugs that can prolong the QT interval further or lower the threshold for TDP, lists of which can be found in public access online databases.

Nadolol, a powerful non-selective beta blocker, has been shown to reduce the arrhythmic risk in all three main genotypes (LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3).

Soon after being notified, the girl's parents reported that her older brother, also deaf, had previously died after a terrible fright.

The establishment of the International Long-QT Syndrome Registry in 1979 allowed numerous pedigrees to be evaluated in a comprehensive manner.