Ganesha

Traditional Ganesha (/gəɳeɕᵊ/, Sanskrit: गणेश, IAST: Gaṇeśa), also spelled Ganesh, and also known as Ganapati, Vinayaka, Pillaiyar, and Lambodara, is one of the best-known and most worshipped deities in the Hindu pantheon[4] and is the Supreme God in the Ganapatya sect.

[8] He is widely revered, more specifically, as the remover of obstacles and bringer of good luck;[9][10] the patron of arts and sciences; and the deva of intellect and wisdom.

[20] Though the earliest mention of the word Ganapati is found in hymn 2.23.1 of the 2nd-millennium BCE Rigveda, it is uncertain that the Vedic term referred specifically to Ganesha.

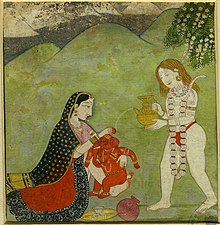

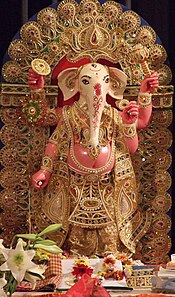

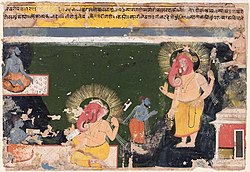

[41] He may be portrayed standing, dancing, heroically taking action against demons, playing with his family as a boy, sitting down on an elevated seat, or engaging in a range of contemporary situations.

In one modern form, the only variation from these old elements is that the lower-right hand does not hold the broken tusk but is turned towards the viewer in a gesture of protection or fearlessness (Abhaya mudra).

[72] Other depictions of snakes include use as a sacred thread (IAST: yajñyopavīta)[73] wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne.

According to this theory, showing Ganesha as master of the rat demonstrates his function as Vigneshvara (Lord of Obstacles) and gives evidence of his possible role as a folk grāma-devatā (village deity) who later rose to greater prominence.

[30] Dhavalikar ascribes the quick ascension of Ganesha in the Hindu pantheon, and the emergence of the Ganapatyas, to this shift in emphasis from vighnakartā (obstacle-creator) to vighnahartā (obstacle-averter).

[99] The concept of buddhi is closely associated with the personality of Ganesha, especially in the Puranic period, when many stories stress his cleverness and love of intelligence.

[107] Though Ganesha is popularly held to be the son of Shiva and Parvati, the Puranic texts give different versions about his birth.

[123] Another popularly-accepted mainstream pattern associates him with the concepts of Buddhi (intellect), Siddhi (spiritual power), and Riddhi (prosperity); these qualities are personified as goddesses, said to be Ganesha's wives.

This story has no Puranic basis, but Anita Raina Thapan and Lawrence Cohen cite Santoshi Ma's cult as evidence of Ganesha's continuing evolution as a popular deity.

[142] He did so "to bridge the gap between the Brahmins and the non-Brahmins and find an appropriate context in which to build a new grassroots unity between them" in his nationalistic strivings against the British in Maharashtra.

[143] Because of Ganesha's wide appeal as "the god for Everyman", Tilak chose him as a rallying point for Indian protest against British rule.

[155] An elephant–headed anthropomorphic figure on Indo-Greek coins from the 1st century BCE has been proposed by some scholars to be "incipient Ganesha", but this has been strongly contested.

An early iconic image of Ganesha with elephant head, a bowl of sweets and a goddess sitting in his lap has been found in the ruins of the Bhumara Temple in Madhya Pradesh, and this is dated to the 5th-century Gupta period.

[161] Narain summarises the lack of evidence about Ganesha's history before the 5th century as follows:[161] What is inscrutable is the somewhat dramatic appearance of Gaṇeśa on the historical scene.

On the one hand, there is the pious belief of the orthodox devotees in Gaṇeśa's Vedic origins and in the Purāṇic explanations contained in the confusing, but nonetheless interesting, mythology.

[166] He is, states Bailey, recognised as goddess Parvati's son and integrated into Shaivism theology by early centuries of the common era.

There is no independent evidence for an elephant cult or a totem; nor is there any archaeological data pointing to a tradition prior to what we can already see in place in the Purāṇic literature and the iconography of Gaṇeśa.Thapan's book on the development of Ganesha devotes a chapter to speculations about the role elephants had in early India but concludes that "although by the second century CE the elephant-headed yakṣa form exists it cannot be presumed to represent Gaṇapati-Vināyaka.

[178] In rejecting any claim that this passage is evidence of Ganesha in the Rig Veda, Ludo Rocher says that it "clearly refers to Bṛhaspati—who is the deity of the hymn—and Bṛhaspati only".

[183] Two verses in texts belonging to Black Yajurveda, Maitrāyaṇīya Saṃhitā (2.9.1)[184] and Taittirīya Āraṇyaka (10.1),[185] appeal to a deity as "the tusked one" (Dantiḥ), "elephant-faced" (Hastimukha), and "with a curved trunk" (Vakratuṇḍa).

Brown notes while the Puranas "defy precise chronological ordering", the more detailed narratives of Ganesha's life are in the late texts, c.

[200] In his survey of Ganesha's rise to prominence in Sanskrit literature, Ludo Rocher notes that:[201] Above all, one cannot help being struck by the fact that the numerous stories surrounding Gaṇeśa concentrate on an unexpectedly limited number of incidents.

Other incidents are touched on in the texts, but to a far lesser extent.Ganesha's rise to prominence was codified in the 9th century when he was formally included as one of the five primary deities of Smartism.

"[205] Lawrence W. Preston considers the most reasonable date for the Ganesha Purana to be between 1100 and 1400, which coincides with the apparent age of the sacred sites mentioned by the text.

[207] However, Phyllis Granoff finds problems with this relative dating and concludes that the Mudgala Purana was the last of the philosophical texts concerned with Ganesha.

[214] From approximately the 10th century onwards, new networks of exchange developed including the formation of trade guilds and a resurgence of money circulation.

[218] The spread of Hindu culture throughout Southeast Asia established Ganesha worship in modified forms in Burma, Cambodia, and Thailand.

[233] Jain ties with the trading community support the idea that Jainism took up Ganesha worship as a result of commercial connections and influence of Hinduism.