Lorenz cipher

Some were deciphered using hand methods before the process was partially automated, first with Robinson machines and then with the Colossus computers.

In the 1920s four men in different countries invented rotor cipher machines to produce a key stream to act instead of a tape.

[13] The logical functioning of the Tunny system was worked out well before the Bletchley Park cryptanalysts saw one of the machines—which only happened in 1945, as Germany was surrendering to the Allies.

[13] The teleprinter characters consisted of five data bits (or "impulses"), encoded in the International Telegraphy Alphabet No.

So enciphering can be shown symbolically as: and deciphering as: Each "Tunny" link had four SZ machines with a transmitting and a receiving teleprinter at each end.

[23] As was normal telegraphy practice, messages of any length were keyed into a teleprinter with a paper tape perforator.

[13] At the receiving end, the operator would similarly connect his SZ machine into the circuit and the output would be printed up on a continuous sticky tape.

A new Y Station, Knockholt in Kent, was later constructed specifically to intercept Tunny traffic so that the messages could be efficiently recorded and sent to Bletchley Park.

[14][25] Over the following two months up to January 1942, Tutte and colleagues worked out the complete logical structure of the cipher machine.

This remarkable piece of reverse engineering was later described as "one of the greatest intellectual feats of World War II".

[14] After this cracking of Tunny, a special team of code breakers was set up under Ralph Tester, most initially transferred from Alan Turing's Hut 8.

It performed the bulk of the subsequent work in breaking Tunny messages, but was aided by machines in the complementary section under Max Newman known as the Newmanry.

These used two paper tapes, along with logic circuitry, to find the settings of the χ pin wheels of the Lorenz machine.

[29] The Robinsons had major problems keeping the two paper tapes synchronized and were relatively slow, reading only 2,000 characters per second.

[30] Colossus proved to be efficient and quick against the twelve-rotor Lorenz SZ42 on-line teleprinter cipher machine.

Some influential figures had doubts about his proposed design for the decryption machine, and Flowers proceeded with the project while partly funding it himself.

It was faster, more reliable and more capable than the Robinsons, so speeding up the process of finding the Lorenz χ pin wheel settings.

[33] This, and the clocking of the electronics from the optically read paper tape sprocket holes, completely eliminated the Robinsons' synchronisation problems.

Bletchley Park management, which had been sceptical of Flowers's ability to make a workable device, immediately began pressuring him to construct another.

After the end of the war, Colossus machines were dismantled on the orders of Winston Churchill,[34] but GCHQ retained two of them.

[35] By the end of the war, the Testery had grown to nine cryptographers and 24 ATS girls (as the women serving that role were then called), with a total staff of 118, organised in three shifts working round the clock.

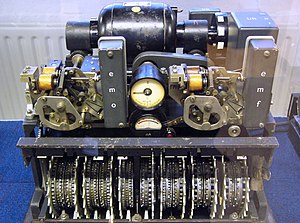

Lorenz cipher machines were built in small numbers; today only a handful survive in museums.

[36] Two further Lorenz machines are displayed at both Bletchley Park and The National Museum of Computing in the United Kingdom.

Another example is on display at the National Cryptologic Museum in Maryland, the United States.

[37][38] It was found to be the World War II military version, was refurbished and in May 2016 installed next to the SZ42 machine in the museum's "Tunny" gallery.