Lorenz system

It is notable for having chaotic solutions for certain parameter values and initial conditions.

The term "butterfly effect" in popular media may stem from the real-world implications of the Lorenz attractor, namely that tiny changes in initial conditions evolve to completely different trajectories.

This underscores that chaotic systems can be completely deterministic and yet still be inherently impractical or even impossible to predict over longer periods of time.

For example, even the small flap of a butterfly's wings could set the earth's atmosphere on a vastly different trajectory, in which for example a hurricane occurs where it otherwise would have not (see Saddle points).

The shape of the Lorenz attractor itself, when plotted in phase space, may also be seen to resemble a butterfly.

In 1963, Edward Lorenz, with the help of Ellen Fetter who was responsible for the numerical simulations and figures,[1] and Margaret Hamilton who helped in the initial, numerical computations leading up to the findings of the Lorenz model,[2] developed a simplified mathematical model for atmospheric convection.

In particular, the equations describe the rate of change of three quantities with respect to time: x is proportional to the rate of convection, y to the horizontal temperature variation, and z to the vertical temperature variation.

[3] The Lorenz equations can arise in simplified models for lasers,[4] dynamos,[5] thermosyphons,[6] brushless DC motors,[7] electric circuits,[8] chemical reactions[9] and forward osmosis.

[10] Interestingly, the same Lorenz equations were also derived in 1963 by Sauermann and Haken [11] for a single-mode laser.

Later on, it was also shown the complex version of Lorenz equations also had laser equivalent ones.

[15][16] The Malkus waterwheel exhibits chaotic motion where instead of spinning in one direction at a constant speed, its rotation will speed up, slow down, stop, change directions, and oscillate back and forth between combinations of such behaviors in an unpredictable manner.

From a technical standpoint, the Lorenz system is nonlinear, aperiodic, three-dimensional and deterministic.

The Lorenz equations have been the subject of hundreds of research articles, and at least one book-length study.

[3] One normally assumes that the parameters σ, ρ, and β are positive.

This pair of equilibrium points is stable only if which can hold only for positive ρ if σ > β + 1.

At the critical value, both equilibrium points lose stability through a subcritical Hopf bifurcation.

[25] For other values of ρ, the system displays knotted periodic orbits.

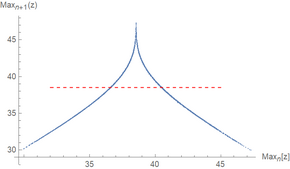

Lorenz also found that when the maximum z value is above a certain cut-off, the system will switch to the next lobe.

Combining this with the chaos known to be exhibited by the tent map, he showed that the system switches between the two lobes chaotically.

[26][27] Standard way: Less verbose: As shown in Lorenz's original paper,[28] the Lorenz system is a reduced version of a larger system studied earlier by Barry Saltzman.

[29] The Lorenz equations are derived from the Oberbeck–Boussinesq approximation to the equations describing fluid circulation in a shallow layer of fluid, heated uniformly from below and cooled uniformly from above.

The fluid is assumed to circulate in two dimensions (vertical and horizontal) with periodic rectangular boundary conditions.

[31] The partial differential equations modeling the system's stream function and temperature are subjected to a spectral Galerkin approximation: the hydrodynamic fields are expanded in Fourier series, which are then severely truncated to a single term for the stream function and two terms for the temperature.

The scientific community accepts that the chaotic features found in low-dimensional Lorenz models could represent features of the Earth's atmosphere ([33][34][35]), yielding the statement of “weather is chaotic.” By comparison, based on the concept of attractor coexistence within the generalized Lorenz model[26] and the original Lorenz model ([36][37]), Shen and his co-authors [35][38] proposed a revised view that “weather possesses both chaos and order with distinct predictability”.

The revised view, which is a build-up of the conventional view, is used to suggest that “the chaotic and regular features found in theoretical Lorenz models could better represent features of the Earth's atmosphere”.

[25] To prove this result, Tucker used rigorous numerics methods like interval arithmetic and normal forms.

Then the proof is split in three main points that are proved and imply the existence of a strange attractor.

The problem is that our estimation may become imprecise after several iterations, thus what Tucker does is to split

Another problem is that as we are applying this algorithm, the flow becomes more 'horizontal',[39] leading to a dramatic increase in imprecision.

To prevent this, the algorithm changes the orientation of the cross sections, becoming either horizontal or vertical.