Lotario (Handel)

Matilde, Berengario's wife and fully his match in ambition and rage, announces that she has bribed Adelaide's soldiers to open the gates of Pavia to their forces.

Berengario takes Pavia easily owing to the treachery of Adelaide's troops but she adamantly refuses to marry his son.

Berengario goes to fight Lotario's army, leaving Adelaide with his wife Matilde, who loads her with chains and throws her in the dungeon.

Matilde is not happy about this outcome however and warns her son to expect pain and Adelaide to look forward to punishment (Aria:Arma lo sguardo).

In captivity, Berengario and Matilde appeal to Adelaide to stop the war by using her influence with Lotario to have them crowned king and queen of Italy.

Clorimondo worries that he may have backed the losing side in this struggle and reflects on the transitory nature of human fortunes (Aria:Alza al ciel).

Adelaide shows them forgiveness; they will be allowed to live in quiet retirement, while out of gratitude for saving her life, Idalberto will be King of Italy.

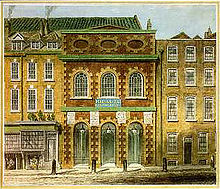

A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers.

[8][9] The Royal Academy of Music collapsed at the end of the 1728–29 season, partly due to the huge fees paid to the star singers, and the two prima donnas who had appeared in Handel's last few operas, Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni both left London for engagements in continental Europe.

"[7] The story of Lotario is, in modern terms, a "prequel" to Handel's previous opera Ottone with many of the same characters at an earlier part of their lives.

Handel was now in business for himself, unlike the arrangements he had with the Royal Academy of Music, which had financial support from wealthy backers.

One of Handel's most loyal supporters, Mary Delany, wrote in a letter of the new ensemble of singers that performed LotarioBernachi has a vast compass, his voice mellow and clear, but not so sweet as Senesino, his manner better; his person not so good, for he is as big as a Spanish friar.

La Strada is the first woman; her voice is without exception fine, her manner perfection, but her person very bad, and she makes frightful mouths.

La Merighi is next to her; her voice is not extraordinarily good or bad, she is tall and has a very graceful person, with a tolerable face; she seems to be a woman about forty, she sings easily and agreeably.

Not all beans are for market, especially beans so badly cooked as this first basketful...[7]Tenors were unusual in leading roles in opera in England, as Rolli notes, although Handel's previous operas Tamerlano and Rodelinda had featured star roles for a celebrated tenor, Francesco Borosini.