Louis Antoine de Saint-Just

He was the designated speaker for the Robespierrists in their conflicts with other political parties in the National Convention, launching accusations and requisitions against figures like Danton or Hébert.

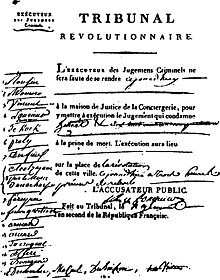

Arrested alongside him, he remained silent until his death the following day, when he was guillotined on the Place de la Révolution with the 104 Robespierrists executed, at the age of 26.

The dark legend surrounding this figure, and Robespierrists in general, persisted in historical research until the second half of the 20th century, before gradually being reassessed from that period onward by more recent historians.

After a promising start, his teachers soon viewed Saint-Just as a troublemaker, a reputation later compounded by infamous stories (almost certainly apocryphal) of how he led a students' rebellion and tried to burn down the school.

[12] Though no evidence of their relationship exists, official records show that on 25 July 1786, Thérèse was married to Emmanuel Thorin, the scion of a prominent local family.

Whatever his true state, it is known that a few weeks after the marriage he abruptly left home for Paris unannounced, having gathered up a pair of pistols and a good quantity of his mother's silver.

[b] The poem, a medieval epic fantasy relaying the quest of young Antoine Organt, extols the virtues of primitive man, praising his libertinism and independence whilst blaming all present-day troubles on modern inequalities of wealth and power.

The notary Gellé, previously an undisputed town leader, was challenged by a group of reformists who were led by several of Saint-Just's friends, including the husband of his sister Louise.

[25] At local meetings he moved attendees with his patriotic zeal and flair: in one much-repeated story, Saint-Just brought the town council to tears by thrusting his hand into the flame of a burning anti-revolutionary pamphlet, swearing his devotion to the Republic.

[33] Spread out over five books, L'Esprit de la Revolution is inconsistent in many of its assertions but still shows clearly that Saint-Just no longer saw government as oppressive to man's nature but necessary to its success: its ultimate object was to "edge society in the direction of the distant ideal.

The episode fostered public anger toward the King which simmered all year until a Parisian mob finally attacked the Tuileries Palace on 10 August 1792.

[55] Amid a flurry of proposals by other deputies, Saint-Just held inflexibly to his "one man one vote" plan, and this conspicuous homage to Greco-Roman traditions (which were particularly prized and idealized in French culture during the Revolution) enhanced his political cachet.

[citation needed] The Girondin leader, Jacques Pierre Brissot, was indicted for treason and scheduled for trial, but the other Brissotins were imprisoned (or pursued) without formal charges.

[58] In its secret negotiations, the Committee of Public Safety was initially unable to form a consensus concerning the jailed deputies, but as some Girondins fled to the provinces and attempted to incite an insurrection, its opinion hardened.

[64] Amid worsening conditions at the front in the fall of that year, several deputies were designated représentant en mission and sent to the critical area of Alsace to shore up the disintegrating Army of the Rhine.

[65] Local politicians were just as vulnerable to him: even Eulogius Schneider, the powerful leader of Alsace's largest city, Strasbourg, was arrested on Saint-Just's order,[71] and much equipment was commandeered for the army.

[71] With this new power he persuaded the chamber to pass the radical Ventôse Decrees, under which the régime would confiscate aristocratic émigré property and distribute it to needy sans-culottes (commoners).

One week after their adoption, he urged that the Decrees be exercised vigorously and hailed them for ushering in a new era: "Eliminate the poverty that dishonors a free state; the property of patriots is sacred but the goods of conspirators are there for the wretched.

One of the thorniest problems, at least to Robespierre, was populist agitator Jacques Hébert, who discharged torrents of criticism against perceived bourgeois Jacobinism in his newspaper, Le Père Duchesne.

"[86] Danton’s criticism of the Terror won him some support,[39] but a financial scandal involving the French East India Company provided a pretext for his downfall.

Their deaths caused deep resentment in the Convention, and their absence only made it more difficult for the Jacobins to influence the dangerously unpredictable masses of sans-culottes.

[64][98] This hotly contested battle on 26 June 1794 saw Saint-Just apply his most draconian measures, ordering all French soldiers who turned away from the enemy to be summarily shot.

[120] According to Barère: "We never deceived ourselves that Saint-Just, cut out as a more dictatorial boss, would have ended up overthrowing him to put himself in his place; we also knew that we stood in the way of his projects and that he would have us guillotined; we had him stopped".

Rising in his support, Robespierre sputtered and lost his voice; his brother Augustin, Philippe Lebas, and other key allies all tried swaying the deputies, but failed.

In later years, these drafts and notes were put together in various collections along with Organt, Arlequin Diogène, L'Esprit de la Revolution, public speeches, military orders, and private correspondence.

[135] Saint-Just also composed a lengthy draft of his philosophical views, De la Nature, which remained hidden in obscurity until its transcription by Albert Soboul in 1951.

[140] Because a return to the natural state is impossible, Saint-Just argues for a government composed of the most educated members of society, who could be expected to share an understanding of the larger social good.

[93] A measure of his change can be inferred from the experience of his former love interest Thérèse, who is known to have left her husband and taken up residence in a Parisian neighborhood near Saint-Just in late 1793.

Camus identifies Saint-Just's successful argument for the execution of Louis XVI as the moment of death for monarchical divine right, a Nietzschean Twilight of the Idols.

Representations of Saint-Just include those found in the novels Stello (1832) by Alfred de Vigny,[160] A Place of Greater Safety (1992) by Hilary Mantel, and The Sandman comic "Thermidor" by Neil Gaiman; as well as in the plays Danton's Death (1835, by Georg Büchner)[161] and Poor Bitos (Pauvre Bitos, ou Le dîner de têtes, 1956, by Jean Anouilh).