Louisiana Creole people

In the early 19th century amid the Haitian Revolution, refugees of both whites and free people of color originally from Saint-Domingue arrived in New Orleans with their slaves having been deported from Cuba, doubled the city's population and helped strengthen its Francophone culture.

New Orleans, in particular, has always retained a significant historical population of Creoles of color, a group mostly consisting of free persons of multiracial European, African, and Native American descent.

[11][12][13] In the twentieth century, the gens de couleur libres in Louisiana became increasingly associated with the term Creole, in part because Anglo-Americans struggled with the idea of an ethno-cultural identity not founded in race.

[18] Under John Law and the Compagnie du Mississippi, efforts to increase the use of engagés in the colony were made, notably including German settlers whose contracts became defunct when the company went bankrupt in 1731.

[39][40] The slaves brought with them their cultural practices, languages, and religious beliefs rooted in spirit and ancestor worship, as well as Catholic Christianity—all of which were key elements of Louisiana Voodoo.

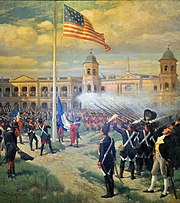

[47] In the summer of 1809, a fleet of ships from the Spanish colony of Cuba landed in New Orleans with more than 9,000 refugees from Saint-Domingue aboard, having been expelled by the island's governor, Marqués de Someruelos.

The evacuation of Saint-Domingue and lately that of the island of Cuba, coupled with the immigration of the people from the East Coast, have tripled in eight years the population of this rich colony, which has been elevated to the status of statehood by virtue of a governmental decree.

Moved by this speech that each of them expressed in his own way, and all in a manner that appeared natural to us, how could we have concealed from them the uncertainty clouding the attempt which we, acting out of gratitude, must make to bring them to Louisiana.

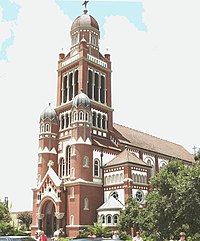

Some Americans were reportedly shocked by aspects of the territory's culture: the predominance of the French language and Roman Catholicism, the class of free Creoles of color and the slaves' African traditions.

Upper-class French Creoles thought that many of the arriving Americans were uncouth, especially the Kentucky boatmen (Kaintucks) who regularly visited, steering flatboats down the Mississippi River filled with goods for market.

[58] As a French, and later Spanish colony, Louisiana maintained a society similar to other Latin American and Caribbean countries, split into three tiers: aristocracy, bourgeoisie, and peasantry.

In addition to the French Canadians, the amalgamated Creole culture in southern Louisiana includes influences from the Chitimacha, Houma and other native tribes, Central and West Africans, Spanish-speaking Isleños (Canary Islanders) and French-speaking Gens de couleur from the Caribbean.

[6] Under the French and Spanish rulers, Louisiana developed a three-tiered society, similar to that of Saint-Domingue (Haiti), Cuba, Brazil, Saint Lucia, Martinique, Guadeloupe and other Latin colonies.

However, Creoles of color, who had long been free before the war, worried about losing their identity and social position, as Anglo-Americans did not legally recognize Louisiana's three-tiered society.

[65] New Iberia's Creole population- men, women, children of all ages, of all classes, including former slaves- were forced to work on Federal projects, digging massive earth fortifications.

[65] Following the Union victory in the Civil War, the Louisiana three-tiered society was gradually overrun by more Anglo-Americans, who classified everyone by the South's binary division of "black" and "white".

During the Reconstruction era, Democrats regained power in the Louisiana state legislature by using paramilitary groups like the White League to suppress black voting.

[74] To fit in the new racial system, especially after the ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson, some Creoles were forced into a position where they had to distance themselves from their black and multiracial cousins; they deliberately erased or destroyed public records, and many "passed over" fully into a white American identity.

[78] Not everyone accepted Drake's actions, and people filed thousands of cases against the office to have racial classifications changed and to protest her withholding legal documents of vital records.

However, the late 2010s have seen a minor but notable resurgence of the Creole identity among linguistic activists of all races,[80] including among white people whose parents or grandparents identify as Cajun or simply French.

[81][82] Contemporary French-language media in Louisiana, such as Télé-Louisiane or Le Bourdon de la Louisiane, often use the term Créole in its original and most inclusive sense (i.e. without reference to race), and some English-language organizations like the Historic New Orleans Collection have published articles questioning the racialized Cajun-Creole dichotomy of the mid-twentieth century.

It is a roux-based meat stew or soup, sometimes made with some combination of any of the following: seafood (usually shrimp, crabs, with oysters optional, or occasionally crawfish), sausage, chicken (hen or rooster), alligator, turtle, rabbit, duck, deer or wild boar.

Alphonse "Bois Sec" Ardoin Zydeco (a transliteration in English of 'zaricô' (snapbeans) from the song, "Les haricots sont pas salés"), was born in black Creole communities on the prairies of southwest Louisiana in the 1920s.

Later, Louisiana Creoles, such as the 20th-century Chénier brothers, Andrus Espree (Beau Jocque), Rosie Lédet and others began incorporating a more bluesy sound and added a new linguistic element to zydeco music: English.

Among the Spanish Creole people highlights, between their varied traditional folklore, the Canarian Décimas, romances, ballads and pan-Hispanic songs date back many years, even to the Medieval Age.

Through innovation, adaptation, interaction, and contact, individuals and groups continuously enrich the French language spoken in Louisiana, infusing it with linguistic features that are sometimes unique to the region.

In steady waves starting in the 1830s to the 1860s and onward, a sizable number of Louisana Creoles had also migrated through- or from Texas into Mexico, often by sea, with particular population concentrations in the state Veracruz – especially Tampico.

The Cane River as well as Avoyelles and St. Landry Creole family surnames include but are not limited to: Antee, Anty, Arceneaux, Arnaud, Balthazar, Barre', Bayonne, Beaudoin, Bellow, Bernard, Biagas, Bossier, Boyér, Brossette, Buard, Byone, Carriere, Cassine, Catalon, Chevalier, Chretien, Christophe, Cloutier, Colson, Colston, Conde, Conant, Coutée, Cyriak, Cyriaque, Damas, DeBòis, DeCuir, Deculus, DeLouche, Delphin, De Sadier, De Soto, Dubreil, Dunn, Dupré.

Esprit, Fredieu, Fuselier, Gallien, Goudeau, Gravés, Guillory, Hebert, Honoré, Hughes, LaCaze, LaCour, Lambre', Landry, Laurent, LéBon, Lefìls, Lemelle, LeRoux, Le Vasseur, Llorens, Mathés, Mathis, Métoyer, Mezière, Monette, Moran, Mullone, Pantallion, Papillion, Porche, PrudHomme, Rachal, Ray, Reynaud, Roque, Sarpy, Sers, Severin, Simien, St. Romain, St. Ville, Sylvie, Sylvan, Tournoir, Tyler, Vachon, Vallot, Vercher and Versher.

The traditions and Creole heritage are prevalent in Opelousas, Port Barre, Melville, Palmetto, Lawtell, Eunice, Swords, Mallet, Frilot Cove, Plaisance, Pitreville, and many other villages, towns and communities.