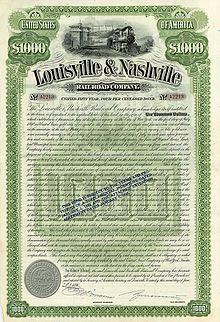

Louisville and Nashville Railroad

Operating under one name continuously for 132 years, it survived civil war and economic depression and several waves of social and technological change.

As one of the premier Southern railroads, the L&N extended its reach far beyond its namesake cities, stretching to St. Louis, Memphis, Atlanta, and New Orleans.

The railroad was economically strong throughout its lifetime, operating freight and passenger trains in a manner that earned it the nickname, "The Old Reliable".

Its first line extended barely south of Louisville, Kentucky, and it took until 1859 to span the 180-odd miles (290 km) to its second namesake city of Nashville.

There were about 250 miles (400 km) of track in the system by the outbreak of the Civil War, and its strategic location, spanning the Union/Confederate lines, made it of great interest to both governments.

During the Civil War, different parts of the network were pressed into service by both armies at various times, and considerable damage from wear, battle, and sabotage occurred.

The company profited from Northern haulage contracts for troops and supplies, paid in sound Federal greenbacks, as opposed to the rapidly depreciating Confederate dollars.

After the war, other railroads in the South were devastated to the point of collapse, and the general economic depression meant that labor and materials to repair its roads could be had fairly cheaply.

[citation needed] Since all locomotives of the time were steam-powered, many railroads had favored coal as their engines' fuel source after wood-burning models were found unsatisfactory.

The L&N guaranteed not only its own fuel sources but a steady revenue stream by pushing its lines into the difficult but coal-rich terrain of eastern Kentucky, and also well into northern Alabama.

There the small town of Birmingham had recently been founded amidst undeveloped deposits of coal, iron ore and limestone, the basic ingredients of steel production.

The arrival of L&N transport and investment capital helped create a great industrial city and the South's first postwar urban success story.

The railroad's access to good coal enabled it to claim for a few years starting in 1940 the nation's longest unrefuelled run, about 490 miles (790 km) from Louisville to Montgomery, Alabama.

Where that wasn't possible, as with the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway (which was older than the L&N), it simply used its financial muscle—in 1880 it acquired a controlling interest in its chief competitor.

In the 1960s, acquisitions in Illinois allowed a long-sought entry into the premier railroad nexus of Chicago, and some of the battered remains of the old rival, the Tennessee Central, were sold to the L&N as well.

In 1979, amid great lamentations in the press, the last passenger service over L&N rails ceased when Amtrak discontinued The Floridian, which had connected Louisville with Nashville and continued to Florida via Birmingham.

It is also the subject of the 2003 Rhonda Vincent bluegrass song "Kentucky Borderline", as well as "The L&N Don't Stop Here Anymore" by Jean Ritchie and individually performed by Michelle Shocked, Johnny Cash, Billy Bragg & Joe Henry, and Kathy Mattea.

The L&N is also mentioned in the Lost Dog Street Band song “Last Train”, written by Benjamin Tod, from their 2024 album Survived.

The Humming Bird and Pan-American, both from Cincinnati to New Orleans and Memphis, were two of the L&N's most popular passenger trains that ran entirely on its own lines.

The city of Atlanta, Georgia, is home to the General and the Texas, two 4-4-0 locomotives originally built for the Western and Atlantic Railroad, which was later leased to L&N predecessor Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis.