Love's Labour's Lost

Love's Labour's Lost is one of William Shakespeare's early comedies, believed to have been written in the mid-1590s for a performance at the Inns of Court before Queen Elizabeth I.

Shakespeare's audiences were familiar with the historical personages portrayed and the political situation in Europe relating to the setting and action of the play.

Scholars suggest the play lost popularity as these historical and political portrayals of Navarre's court became dated and less accessible to theatergoers of later generations.

The play's sophisticated wordplay, pedantic humour and dated literary allusions may also be causes for its relative obscurity, as compared with Shakespeare's more popular works.

Ferdinand, King of Navarre, and his three noble companions, the Lords Berowne, Dumaine, and Longaville, take an oath not to give in to the company of women.

Don Adriano de Armado, a Spaniard visiting the court, writes a letter to tell the King of a tryst between Costard and Jaquenetta.

The Princess of France and her ladies arrive, wishing to speak to the King regarding the cession of Aquitaine, but must ultimately make their camp outside the court due to the decree.

Berowne confesses to breaking the oath, explaining that the only study worthy of mankind is that of love, and he and the other men collectively decide to relinquish the vow.

Impressed by the ladies' wit, the men apologize, and when all identities are righted, they watch Holofernes, Sir Nathaniel, Costard, Moth and Don Armado present the Nine Worthies.

The Princess makes plans to leave at once, and she and her ladies, readying for mourning, declare that the men must wait a year and a day to prove their loves lasting.

[1] Some possible influences on Love's Labour's Lost can be found in the early plays of John Lyly, Robert Wilson's The Cobbler's Prophecy (c. 1590) and Pierre de La Primaudaye's L'Academie française (1577).

"[5] Critics have attempted to draw connections between notable Elizabethan English persons and the characters of Don Armado, Moth, Sir Nathaniel, and Holofernes, with little success.

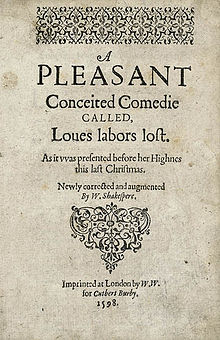

[7] Dating to 1598, Edinburgh University's manuscript is one of the earliest known copies of the work and according to its title page, is the same version as that which was presented to Queen Elizabeth I the previous Christmas, in 1597.

[16] In 1935 Frances Yates asserted that the title derived from a line in John Florio's His firste Fruites (1578): "We neede not speak so much of loue, al books are ful of lou, with so many authours, that it were labour lost to speake of Loue",[17] a source from which Shakespeare also took the untranslated Venetian proverb Venetia, Venetia/Chi non ti vede non ti pretia (LLL 4.2.92–93) ("Venice, Venice, Who does not see you cannot praise you").

[18] Love's Labour's Lost abounds in sophisticated wordplay, puns, and literary allusions and is filled with clever pastiches of contemporary poetic forms.

[19][20] The satirical allusions of Navarre's court are likewise inaccessible, "having been principally directed to fashions of language that have long passed away, and [are] consequently little understood, rather than in any great deficiency of invention.

The men's sexual appetite manifests in their desire for fame and honour; the notion of women as dangerous to masculinity and intellect is established early on.

[23] Critic Mark Breitenberg commented that the use of idealistic poetry, popularized by Petrarch, effectively becomes the textualized form of the male gaze.

Though the play entwines fantasy and reality, the arrival of the messenger to announce the death of the Princess's father ultimately brings this notion to a head.

Lewis concluded that "the proclivity to rationalize a position, a like, or a dislike, is linked in Love's Labour's Lost with the difficulty of reckoning absolute value, whose slipperiness is indicated throughout the play.

"[24] Critic Joseph Westlund wrote that Love's Labour's Lost functions as a "prelude to the more extensive commentary on imagination in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Within moments of swearing their oath, it becomes clear that their fantastical goal is unachievable given the reality of the world, the unnatural state of abstinence itself, and the arrival of the Princess and her ladies.

The manner in which it was played last night destroyed the brilliancy completely, and left a residuum of insipidity which was encumbered rather than relieved by the scenery and decorations.

[30] Notable 20th-century British productions included a 1936 staging at the Old Vic featuring Michael Redgrave as Ferdinand and Alec Clunes as Berowne.

"[34] In late summer 2005, an adaptation of the play was staged in the Dari language in Kabul, Afghanistan by a group of Afghan actors, and was reportedly very well received.

Dominic Cavendish of the Telegraph called it "the most blissfully entertaining and emotionally involving RSC offering I've seen in ages" and remarked that "Parallels between the two works – the sparring wit, the sex-war skirmishes, the shift from showy linguistic evasion to heart-felt earnestness – become persuasively apparent.

[38] Thomas Mann in his novel Doctor Faustus (1943) has the fictional German composer Adrian Leverkühn attempt to write an opera on the story of the play.

[40] The 2004 ska musical The Big Life is based on Love's Labour's Lost, reworked to be about the Windrush generation arriving in London.

The cast included Michael Kitchen as Ferdinand; John McEnery as Berowne; Anna Massey as the Princess of France; Eileen Atkins as Rosaline; and Paul Scofield as Don Adriano.

[48] A modern-language adaptation of the play, titled Groups of Ten or More People, was released online by Chicago-based company Littlebrain Theatre in July 2020.