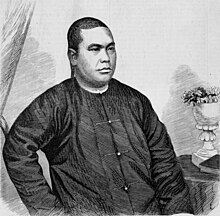

Lowe Kong Meng

Born into a trading family in Penang, Kong Meng learned English and French at an early age and worked as an importing merchant around the Indian Ocean.

After 1860, as the Chinese population in Melbourne peaked, he diversified into other lines of business, including investing in the Commercial Bank of Australia.

He was a leading defender of Chinese Australians at a time when their status was politically controversial and they were subjected to targeted taxation, discrimination and violence.

[4] To avoid this, it was common for Chinese migrants to disembark at Robe in the neighbouring colony of South Australia and walk the 350 kilometres (220 mi) to the goldfields in Victoria.

In 1857, he testified before a Victorian parliamentary committee, arguing that clear laws would give Chinese migrants more confidence to settle in Australia with their families.

[12] In 1879, with Louis Ah Mouy and Cheok Hong Cheong, Kong Meng published a pamphlet The Chinese Question in Australia.

The authors also pointed to obligations in the Anglo-Chinese Peking Convention of 1860 which granted reciprocal rights for Chinese people to travel and work in the British Empire.

[14][15] In 1887, the Zongli Yamen (the Qing ministry of foreign affairs[16]), sent two imperial commissioners to Australia to investigate the treatment of Chinese Australians.

[18][17] Kong Meng presented a petition to the commissioners co-signed with Louis Ah Mouy and Cheok Hong Cheong.

In 1867, the couple attended a fancy-dress ball in honour of the Duke of Edinburgh, Kong Meng wearing a mandarin's robes, while she dressed as a Grecian lady.

Contemporary accounts described him with words like "cultured", "influential" and "highly esteemed" and reference extensive donations to charities and churches.

[20] Elsewhere, The Bulletin relates a story of Kong Meng being accosted on a bus to Richmond by a "cheeky youth" who assumed he could not speak English.

Kong Meng purportedly responded that he could happy converse in 6 languages, but requested that he not be addressed "in a dialect which should only be used by you for conversing with your own social equals.”[21] In 1863, Kong Meng was awarded the title Mandarin of the Blue Button by the Tongzhi Emperor in recognition of his leadership of the Chinese community in Melbourne.

[3] The Argus reported that his funeral procession was made up of about 100 vehicles, and the route was lined by many people, including many Chinese Melburnians.

In 1916, his son George wrote to The Age[24] and The Argus,[25] complaining that he had been rebuffed while attempting to enlist to fight in the First World War.

An editorial in the Euroa Gazette described the decision as unjust, calling the Kong Meng family "old and highly respected" in both Victoria's north-east and in Melbourne.

Twenty-eight years after his death, it recalled Lowe Kong Meng as a "a gentleman of great public spirit, scrupulously honourable in all his dealings, and very highly esteemed by the citizens".