Lusaka

The BSAC built a railway linking their mines in the Copperbelt to Cape Town and Lusaka was designated as a water stop on that line, named after a local Lenje chief called Lusaaka.

In 1929, five years after taking over control of Northern Rhodesia from the BSAC, the British colonial administration decided to move its capital from Livingstone to a more central location, and Lusaka was chosen.

Large-scale migration of people from other areas of Zambia occurred both before and after independence, and a lack of sufficient formal housing led to the emergence of numerous unplanned shanty towns on the city's western and southern fringes.

[12] In the 19th century, African and European slave traders began arriving from the coastal regions of modern-day Tanzania, Mozambique and Angola, enslaving members of the Soli and Lenje communities for shipment to the Middle East, Europe and South America.

[14] Rhodes was a strong believer in the Cape to Cairo railway project, although with German East Africa blocking the route to the north of BSAC territory, he could not progress it during his lifetime.

[15] With little regard for the prior rights of the African populations, Rhodes directed the expansion of territorial control as far as Salisbury (now Harare in Zimbabwe), and his company continued extending to the north even after his death in 1902.

This created an almost continuous line of British colonies from South Africa through to Egypt and led to the revival of projects for the Cape to Cairo railway and a similar road route.

[15][24] The British imperial government took direct control of Northern Rhodesia in 1924, through a governor and legislative council, but the BSAC retained its rights over mining acquired in prior decades.

[29] In March 1929, the UK's Colonial Office sent a telegram to the Northern Rhodesian government recommending that the capital of the territory be moved, citing "communications" and also "health" reasons.

[29] Keen to avoid the informal development of the townships that were emerging close to mining areas, Alexander recommended that a town planner be recruited to design the capital.

[31] The water engineer's investigations concluded that there was sufficient groundwater,[13] and the report confirming Lusaka as the planned capital was approved by the legislative council in July 1931.

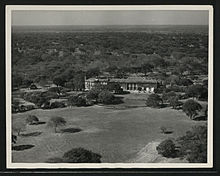

Seeking to emulate the Cyprus building, as well as the recently completed viceroy's mansion in New Delhi, Storrs commissioned several top architects to work on the plan, which was presented at the Royal Academy.

[37] After the royal visit, Young wrote to the Colonial Office that he was "optimistic about the future of Lusaka", and he appointed administrator Eric Dutton to lead the project.

Young refused their demand to compensate them financially, but he sought to placate them by establishing Livingstone as the protectorate's tourism capital, with a new museum and a game reserve.

[39] Under Adshead's original plans, Lusaka was proposed as a pure administrative centre, with no industry or large African population; he commented at one point that it "could never become an important city".

[47] The need for metals during World War II led to a boom in the copper industry which, accompanied by a 1941 excess-profits tax ordered by the UK, brought increased revenue to the government.

Lusaka's African workforce, which remained relatively unskilled, did not benefit as much as that of the Copperbelt, where a shortage of skilled mining labour had led to improved pay.

Authorities in London cited the economic benefits and the belief that the merged territory would form a "multiracial state" to counter the rise of Apartheid in South Africa.

[50] In contrast to South Africa, where the government regularly bulldozed them, the authorities in Rhodesia tolerated these squatter areas although they provided no services and Africans continued to live under strict legal constraints.

[52] As discontent with federation rose, a new group of African leaders emerged in the late 1950s, seeking majority rule and independence for Northern Rhodesia, as had recently been attained in Ghana.

After a civil disobedience in 1962, led by Kenneth Kaunda's United National Independence Party (UNIP), the UK Government agreed to a new constitution under which Africans took control of the legislature.

[55] This was the first time that good-quality housing with public utilities had been built for the African population, although it was largely limited to civil servants and copper-industry workers, with the majority of residents continuing to live in the informal settlements.

[55][56] Although Zambia, Malawi and Tanzania had achieved independence by the mid-1960s,[51][57] the other nearby territories of Mozambique, Angola, Southern Rhodesia and South Africa were still under white minority control.

[58] The 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Southern Rhodesia and subsequent UN embargo and eventual border closure impacted Zambia's economy, depriving it of its principal trade route.

The slow-down also highlighted what American political scientist John Harbeson described as a "massive and inefficient parastatal sector as well as the government's prevailing urban bias", and led to a fall in formal employment in Lusaka which continued for several decades.

[60] The lack of jobs decreased the level of rural-to-urban migration in Zambia,[61] but the decline of the copper industry caused a large movement of people from the Copperbelt cities to Lusaka.

[63] In 2018, the city council began a programme of road improvements to tackle chronic traffic congestion, but the lack of quality housing and services remains an issue as of 2021.

[70] The geology of Lusaka is divided between uneven-depth folded and faulted schist in the north, and limestone with dolomitic marble in the south, to a depth of 120 metres (390 ft).

[74] Lusaka's central business district (CBD) is located in the area surrounding Cairo Road, to the west of the Zambia Railways line from Livingstone to the Copperbelt.

Cairo Road, a north–south multi-lane highway roughly four kilometres (2+1⁄2 mi) in length,[75] is the CBD's main artery, which features office buildings as well as shops, cafes and other retail businesses.