M'Naghten rules

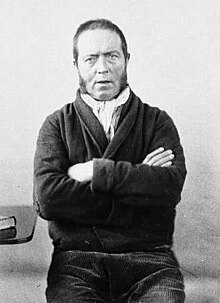

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test defining the defence of insanity that was formulated by the House of Lords in 1843.

[4] The acquittal of M'Naghten on the basis of insanity, a hitherto unheard-of defence per se in modern form, caused a public uproar, with protests from the establishment and the press, even prompting Queen Victoria to write to Robert Peel calling for a "wider interpretation of the verdict".

[6][7] The rules so formulated as M'Naghten's Case 1843 10 C & F 200,[8] or variations of them, are a standard test for criminal liability in relation to mentally disordered defendants in various jurisdictions, either in common law or enacted by statute.

When mental incapacity is successfully raised as a defence in a criminal trial it absolves a defendant from liability: it applies public policies in relation to criminal responsibility by applying a rationale of compassion, accepting that it is morally wrong to punish a person if that person is deprived permanently or temporarily of the capacity to form a necessary mental intent that the definition of a crime requires.

In pre-Norman times in England there was no distinct criminal code – a murderer could pay compensation to the victim's family under the principle of "buy off the spear or bear it".

whether the accused is totally deprived of his understanding and memory and knew what he was doing "no more than a wild beast or a brute, or an infant".The next major advance occurred in Hadfield's Trial 1800 27 How St. Tr.

In Lord Denning's judgement in Bratty v Attorney-General for Northern Ireland 1963 AC 386, whenever the defendant makes an issue of his state of mind, the prosecution can adduce evidence of insanity.

In R v Clarke 1972 1 All E R 219 a defendant charged with a shoplifting claimed she had no mens rea because she had absent-mindedly walked out of the shop without paying because she suffered from depression.

This is partly based on risk of recurrence, whereby the High Court of Australia has expressed that the defence of automatism is unable to be considered when the mental disorder has been proved transient and as such not likely to recur.

LR 685, the defendant smashed a van through the entrance gates of a holiday camp because "It was like a secret society in there, I wanted to do my bit against it" as instructed by God.

It was held that, as the defendant had been aware of his actions, he could neither have been in a state of automatism nor insane, and the fact that he believed that God had told him to do this merely provided an explanation of his motive and did not prevent him from knowing that what he was doing was wrong in the legal sense.

As an example of a contrasting interpretation in which defendant lacking knowledge that the act was morally wrong meets the M'Naghten standards, there are the instructions the judge is required to provide to the jury in cases in New York State when the defendant has raised an insanity plea as a defence: ... with respect to the term "wrong", a person lacks substantial capacity to know or appreciate that conduct is wrong if that person, as a result of mental disease or defect, lacked substantial capacity to know or appreciate either that the conduct was against the law or that it was against commonly held moral principles, or both.

[15][16] There is other support in the authorities for this interpretation of the standards enunciated in the findings presented to the House of Lords regarding M'Naghten's case: If it be accepted, as can hardly be denied, that the answers of the judges to the questions asked by the House of Lords in 1843 are to be read in the light of the then existing case-law and not as novel pronouncements of a legislative character, then the [Australian] High Court's analysis in Stapleton's Case is compelling.

Their exhaustive examination of the extensive case-law concerning the defence of insanity prior to and at the time of the trial of M'Naughten establishes convincingly that it was morality and not legality which lay as a concept behind the judges' use of "wrong" in the M'Naghten rules.

Section 1 of the United Kingdoms' Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991[18] provides that a jury shall not return a special verdict that "the accused is not guilty by reason of insanity" except on the written or oral evidence of two or more registered medical practitioners of whom at least one has special experience in the field of mental disorder.