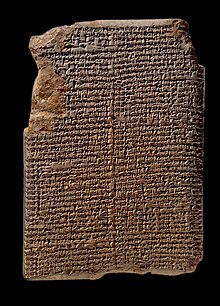

MUL.APIN

The text is preserved in a 7th-century BCE copy on a pair of tablets, named for their incipit, corresponding to the first constellation of the year, MULAPIN "The Plough", identified with stars in the area of the modern constellations of Cassiopeia, Andromeda and Triangulum according to the compilation of suggestions by Gössmann[2] and Kurtik.

The astrophysicist Bradley Schaefer and the astronomer Teije de Jong computed that the dates of the heliacal risings and settings in these tablets fit in the region of Assur at around the year 1370±100 BCE (Schaefer)[9][10] or roughly the epoch between 1400 and 1100 BCE (de Jong).

[11] Watson and Horowitz[6] have shown that the text style changes from low to high complexity from one list to the other.

Tablet 1 has six main sections: Most of these stars and constellations are further attributed to a variety of Near Eastern deities.

To judge from its opening line it started with a section of scholarly explanations of celestial omens.

[12] This suggests that the data had been made to fit or had been read from a globe (if it existed which has no archaeological proof but is an appropriate hypothesis and is highly likely after the 4th century BCE when it is proven in Greece).

Dividing the celestial equator by 360, we obtain the degrees of right ascension (°RA) equaling the Babylonian unit 1 UŠ (one span)[12] or one ideal day.

On the first tablet, texts and data are – at least for us – sufficient to reconstruct the Babylonian celestial globe:[17][18] List 6 reports the path of the moon that later became the zodiac.

So all you have to do is setting up a vertical pole marking the southern direction and observe the star there.

In later epochs of Babylonian astronomy, the observers took bright stars instead of constellations (areas) but originally, the accuracy in time measurement apparently was only sufficient to synchronize water clocks with constellations passing through the meridian.

The pre-condition is having built a celestial globe or another map of the sky which would be possible with the information on MUL.APIN's tablet I.

In list 2 of the 2nd tablet (lines II i 9-21), MUL.APIN contains the first calendar rule: It is written how to use Sirius and the observations of the moon in the 4th, 7th, 10th and 1st month to determine the cardinal points of the year.

However, the uncertainty of the observation means that we can estimate the position constellation Iku rising at a given ideal day (which translates into point coordinates with computation) only within an error bar that extents to the diameter of its area.