Ninurta

He was regarded as the son of the chief god Enlil and his main cult center in Sumer was the Eshumesha temple in Nippur.

The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) built a massive temple for him at Kalhu, which became his most important cult center from then on.

In the epic poem Lugal-e, Ninurta slays the demon Asag using his talking mace Sharur and uses stones to build the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to make them useful for irrigation.

It has been suggested that Ninurta was the inspiration for the figure of Nimrod, a "mighty hunter" who is mentioned in association with Kalhu in the Book of Genesis, although the view has been disputed.

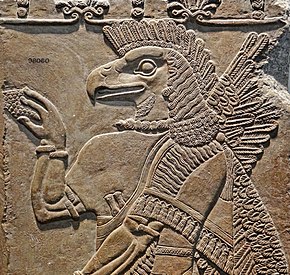

[a] In the nineteenth century, Assyrian stone reliefs of winged, eagle-headed figures from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu were commonly, but erroneously, identified as "Nisrochs" and they appear in works of fantasy literature from the time period.

Ninurta was worshipped in Mesopotamia as early as the middle of the third millennium BC by the ancient Sumerians,[4] and is one of the earliest attested deities in the region.

[4][1] His main cult center was the Eshumesha temple in the Sumerian city-state of Nippur,[4][1][5] where he was worshipped as the god of agriculture and the son of the chief-god Enlil.

[4][1][5] Though they may have originally been separate deities,[1] in historical times, the god Ninĝirsu, who was worshipped in the Sumerian city-state of Girsu, was always identified as a local form of Ninurta.

[4][7][6][8] The walls of the temple were decorated with stone relief carvings, including one of Ninurta slaying the Anzû bird.

Ashurnasirpal II's son Shalmaneser III (ruled 859–824 BC) completed Ninurta's ziggurat at Kalhu and dedicated a stone relief of himself to the god.

[4] The temple of Ninurta at Kalhu flourished until the end of the Assyrian Empire,[4] hiring the poor and destitute as employees.

[9] One speculative hypothesis holds that the winged disc originally symbolized Ninurta during the ninth century BC,[6] but was later transferred to Aššur and the sun-god Shamash.

[24] In the Sumerian poem Lugal-e, also known as Ninurta's Exploits, a demon known as Asag has been causing sickness and poisoning the rivers.

[39] Enki senses his thoughts and creates a giant turtle, which he releases behind Ninurta and which bites the hero's ankle.

[39][40] The end of the story is missing;[41] the last legible portion of the account is a lamentation from Ninurta's mother Ninmah, who seems to be considering finding a substitute for her son.

[45] Black and Green describe these opponents as "bizarre minor deities";[2] they include the six-headed Wild Ram, the Palm Tree King, the seven-headed serpent and the Kulianna the Mermaid (or "fish-woman").

[10] Some of these foes are inanimate objects, such as the Magillum Boat, which carries the souls of the dead to the Underworld, and the strong copper, which represents a metal that was conceived as precious.

[4] Many scholars agree that Ninurta was probably the inspiration for the biblical figure Nimrod, mentioned in Genesis 10:8–12 as a "mighty hunter".

[51] Saint Augustine of Hippo refers to Nimrod in his book The City of God as "a deceiver, oppressor and destroyer of earth-born creatures.

The Dutch demonologist Johann Weyer listed Nisroch in his Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (1577) as the "chief cook" of Hell.

[52] Nisroch appears in Book VI of John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost (first published in 1667) as one of Satan's demons.

[53] In the 1840s, the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard uncovered numerous stone carvings of winged, eagle-headed genii at Kalhu.

[4][6] In Edith Nesbit's classic 1906 children's novel The Story of the Amulet, the child protagonists summon an eagle-headed "Nisroch" to guide them.

"[4] Some modern works on art history still repeat the old misidentification,[6] but Near Eastern scholars now generally refer to the "Nisroch" figure as a "griffin-demon".

[6] In 2016, during its brief conquest of the region, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) demolished Ashurnasirpal II's ziggurat of Ninurta at Kalhu.

[7] This act was in line with ISIL's longstanding policy of destroying any ancient ruins which it deemed incompatible with its militant interpretation of Islam.

[7] According to a statement from the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR)'s Cultural Heritage Initiatives, ISIL may have destroyed the temple to use its destruction for future propaganda[7] and to demoralize the local population.

[7] In March 2020, archaeologists announced the discovery of a 5,000-year-old cultic area filled with more than 300 broken ceremonial ceramic cups, bowls, jars, animal bones and ritual processions dedicated to Ningirsu at the site of Girsu.