Maccabean Revolt

This repression triggered the revolt that Antiochus IV had feared, with a group of Jewish fighters led by Judas Maccabeus (Judah Maccabee) and his family rebelling in 167 BCE and seeking independence.

[7][8] Cultural change did happen, but was largely driven by Jews themselves inspired by ideas from abroad; Greek rulers did not undertake explicit programs of forced Hellenization.

This conflict was largely political rather than cultural; all sides, at this point, were "Hellenized", content with Seleucid rule, and primarily divided over Menelaus's alleged corruption and sacrilege.

His psychopathic tendency was exacerbated by resentment at what the siege had cost him, and he tried to force the Jews to violate their traditional codes of practice by leaving their infant sons uncircumcised and sacrificing pigs on the altar.

[18] After Mattathias' death about one year later in 166 BCE, his son Judas Maccabeus (Hebrew: Judah Maccabee) led a band of Jewish dissidents that would eventually absorb other groups opposed to Seleucid rule and grow into an army.

Regent Lysias, preoccupied with internal Seleucid affairs, agreed to a political compromise that revoked Antiochus IV's ban on Jewish practices.

He recruited devout Jews and sent them into Judea to concentrate his allies where they could be protected, although this influx of refugees would soon create food scarcity issues in the land the Maccabees held.

This tactic would force Judas to respond in open battle, lest his reputation be damaged by inaction and Alcimus's faction gain strength by claiming he was better positioned to protect the people from future killings.

Bacchides fortified cities across the land, put allied Greek-friendly Jews in command in Jerusalem, and ensured children of leading families were held as hostages as a guarantee of good behavior.

The Maccabees avoided direct conflict with the Seleucids, but the internal Jewish civil struggle continued: the rebels harassed, exiled, and killed Jews seen as insufficiently anti-Greek.

King Demetrius was fending off a challenge from Alexander Balas, and agreed to withdraw Seleucid forces from the fortified towns and garrisons in Judea, barring Beth-Zur and Jerusalem.

[44] King Antiochus VII would personally invade and besiege Jerusalem in 134 BCE, but after Hyrcanus paid a ransom and ceded the cities of Joppa and Gazara, the Seleucids left peacefully.

The sarissa was a powerful weapon; it was held in two hands and had great reach (approximately ~6 meters), making it difficult for opponents to approach a phalanx of sarissa-wielding infantry safely.

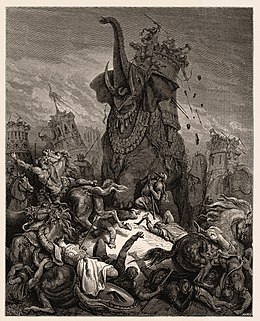

[56] The Seleucids also had access to trained war elephants imported from India, who sported natural armor in their thick hides and could terrify opposing soldiers and their horses.

[57] In terms of army size, the respected historian Polybius reports that in 165 BCE, a military parade near the Seleucid capital Antioch held by Antiochus IV consisted of 41,000 foot soldiers and 4,500 cavalrymen.

These soldiers were preparing to fight in an expedition to the east, not in Judea, but give a rough estimate to the total size of the Seleucid forces in the Western part of their empire capable of being deployed wherever the ruler needed them, not including local auxiliaries and garrisons.

[59] The Maccabees started as a guerrilla force that likely used the traditional weapons effective in small unit combat in mountainous terrain: archers, slingers, and light infantry peltasts armed with sword and shield.

[61] It is speculated that diaspora Jews in countries hostile to the Seleucids, such as Ptolemaic Egypt and Pergamon, may have joined the cause as volunteers, bringing their own local talents to the rebel army.

[62][note 3] After Jonathan was legitimized as high priest and governor by the Seleucid rulers, the Hasmoneans had easier access to recruitment; 20,000 soldiers are reported as repulsing Cendebeus in 139 BCE.

[65] Seleucid phalanxes trained for mountain combat would fight at somewhat greater distance from each other compared to packed lowland formations, and used slightly shorter but more maneuverable Roman-style pikes.

Its depictions of battles are detailed and seemingly accurate, although it portrays implausibly large numbers of Seleucid soldiers, to better emphasize God's aid and Judas's talents.

While the parallels are not as stark as Daniel, some of its depictions of oppression seem influenced by Antiochus's persecution, such as General Holofernes demolishing shrines, cutting down sacred groves, and attempting to destroy all worship other than of the king.

[86] The Testament of Moses, similar to the Book of Daniel, provides a witness to Jewish attitudes leading up to the revolt: it describes persecution, denounces impious leaders and priests as collaborators, praises the virtues of martyrdom, and predicts God's retribution upon the oppressors.

The commentary (pesher) describes a situation wherein a "Righteous Teacher" is unfairly driven from their post and into exile by a "Wicked Priest" and a "Man of the Lie" (possibly the same person).

Many figures have been proposed as the identity of the people behind these titles; one theory goes that the Righteous Teacher was whoever held the High Priest position after Alcimus's death in 159 BCE, perhaps a Zadokite.

Written after the revolt was complete, the books urged unity among the Jews; they describe little of the Hellenizing faction other than to call them lawless and corrupt, and downplay their relevance and power in the conflict.

She advances the view that the loss of civil rights by the Jews in 168 BCE was an administrative punishment in the aftermath of local unrest over increased taxes; that the struggle was fundamentally economic, and merely interpreted as religiously driven in retrospect.

Assuming that Antiochus IV would not have started an ethno-religious persecution for irrational reasons is an ahistorical position in this criticism, as many leaders both ancient and modern clearly were motivated by religious concerns.

[115] The portrayal of an evil tyrant like Antiochus IV attacking the holy city of Jerusalem in the Book of Daniel became a common theme during later Roman rule of Judea, and would contribute to Christian conceptions of the Antichrist.

In earlier Jewish works, devotion to God and adherence to the law led to rewards and punishments in life: the observant would prosper, and disobedience would result in disaster.