Niccolò Machiavelli

[10] He advised rulers to engage in evil when political necessity requires it, and argued specifically that successful reformers of states should not be blamed for killing other leaders who could block change.

[17] Machiavelli's political realism has continued to influence generations of academics and politicians, and his approach has been compared to the Realpolitik of figures such as Otto von Bismarck.

The Italian city-states, and the families and individuals who ran them could rise and fall suddenly, as popes and the kings of France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire waged acquisitive wars for regional influence and control.

[27] From 1502 to 1503, he witnessed the brutal reality of the state-building methods of Cesare Borgia (1475–1507) and his father, Pope Alexander VI, who were then engaged in the process of trying to bring a large part of central Italy under their possession.

[34] Despite being subjected to torture[33] ("with the rope", in which the prisoner is hanged from his bound wrists from the back, forcing the arms to bear the body's weight and dislocating the shoulders), he denied involvement and was released after three weeks.

Machiavelli then retired to his farm estate at Sant'Andrea in Percussina, near San Casciano in Val di Pesa, where he devoted himself to studying and writing political treatises.

[43] As a political theorist, Machiavelli emphasized the "necessity" for the methodical exercise of brute force or deceit, including extermination of entire noble families, to head off any chance of a challenge to the prince's authority.

[44] Scholars often note that Machiavelli glorifies instrumentality in state building, an approach embodied by the saying, often attributed to interpretations of The Prince, "The ends justify the means".

Force may be used to eliminate political rivals, destroy resistant populations, and purge the community of other men strong enough of a character to rule, who will inevitably attempt to replace the ruler.

[56] The Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) argued that Machiavelli's audience was the common people, as opposed to the ruling class, who were already made aware of the methods described through their education.

[59] He excuses Romulus for murdering his brother Remus and co-ruler Titus Tatius to gain absolute power for himself in that he established a "civil way of life".

Pocock, in the so-called "Cambridge School" of interpretation, have asserted that some of the republican themes in Machiavelli's political works, particularly the Discourses on Livy, can be found in medieval Italian literature which was influenced by classical authors such as Sallust.

He undertook to describe simply what rulers actually did and thus anticipated what was later called the scientific spirit in which questions of good and bad are ignored, and the observer attempts to discover only what really happens.Machiavelli felt that his early schooling along the lines of traditional classical education was essentially useless for the purpose of understanding politics.

Leo Strauss declared himself inclined toward the traditional view that Machiavelli was self-consciously a "teacher of evil", since he counsels the princes to avoid the values of justice, mercy, temperance, wisdom, and love of their people in preference to the use of cruelty, violence, fear, and deception.

[81] Italian anti-fascist philosopher Benedetto Croce (1925) concludes Machiavelli is simply a "realist" or "pragmatist" who accurately states that moral values, in reality, do not greatly affect the decisions that political leaders make.

[83] On the other hand, Walter Russell Mead has argued that The Prince's advice presupposes the importance of ideas like legitimacy in making changes to the political system.

[85] In his opinion, Christianity, along with the teleological Aristotelianism that the Church had come to accept, allowed practical decisions to be guided too much by imaginary ideals and encouraged people to lazily leave events up to providence or, as he would put it, chance, luck or fortune.

[87] On the other hand, humanism in Machiavelli's time meant that classical pre-Christian ideas about virtue and prudence, including the possibility of trying to control one's future, were not unique to him.

Machiavelli's promotion of ambition among leaders while denying any higher standard meant that he encouraged risk-taking, and innovation, most famously the founding of new modes and orders.

As Harvey Mansfield (1995, p. 74) wrote: "In attempting other, more regular and scientific modes of overcoming fortune, Machiavelli's successors formalized and emasculated his notion of virtue."

Strauss concludes his 1958 book Thoughts on Machiavelli by proposing that this promotion of progress leads directly to the advent of new technologies being invented in both good and bad governments.

Machiavelli's judgment that governments need religion for practical political reasons was widespread among modern proponents of republics until approximately the time of the French Revolution.

Also in this case, even though there are classical precedents, Machiavelli's insistence on being both realistic and ambitious, not only admitting that vice exists but being willing to risk encouraging it, is a critical step on the path to this insight.

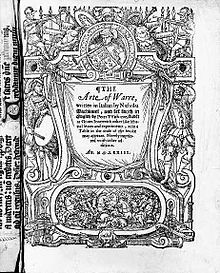

[96] To quote Robert Bireley:[97] ...there were in circulation approximately fifteen editions of the Prince and nineteen of the Discourses and French translations of each before they were placed on the Index of Paul IV in 1559, a measure which nearly stopped publication in Catholic areas except in France.

Pole reported that The Prince was spoken of highly by Thomas Cromwell in England and had influenced Henry VIII in his turn towards Protestantism, and in his tactics, for example during the Pilgrimage of Grace.

[98] A copy was also possessed by the Catholic king and emperor Charles V.[99] In France, after an initially mixed reaction, Machiavelli came to be associated with Catherine de' Medici and the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

Modern political philosophy tended to be republican, but as with the Catholic authors, Machiavelli's realism and encouragement of innovation to try to control one's own fortune were more accepted than his emphasis upon war and factional violence.

"[120] Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson followed Machiavelli's republicanism when they opposed what they saw as the emerging aristocracy that they feared Alexander Hamilton was creating with the Federalist Party.

[124] The Founding Father who perhaps most studied and valued Machiavelli as a political philosopher was John Adams, who profusely commented on the Italian's thought in his work, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America.

[138] Besides being a statesman and political scientist, Machiavelli also translated classical works, and was a playwright (Clizia, Mandragola), a poet (Sonetti, Canzoni, Ottave, Canti carnascialeschi), and a novelist (Belfagor arcidiavolo).