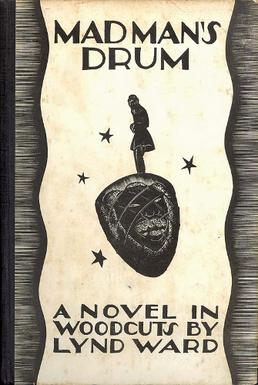

Madman's Drum

Madman's Drum is considered less successfully executed than Gods' Man, and Ward streamlined his work in his next wordless novel, Wild Pilgrimage (1932).

Driven insane by the loss of all who were close to him, he equips himself with the forbidden drum to play music with a leering piper who has roamed his grounds for years.

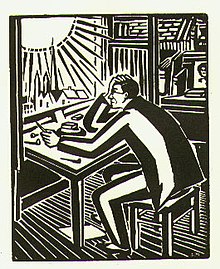

[6] Ward spent a year studying wood engraving in Leipzig, Germany, where he encountered German Expressionist art and read the wordless novel The Sun[a] (1919) by Flemish woodcut artist Frans Masereel (1889–1972).

[8] Nückel's only work in the genre, Destiny told of the life and death of a prostitute in a style inspired by Masereel's, but with a greater cinematic flow.

[8] In his second such work, Madman's Drum, he hoped to explore more deeply the potential of the narrative medium, and to overcome what he saw as a lack of individuality in the characters in Gods' Man.

[15] The original woodblocks are in the Lynd Ward Collection in the Joseph Mark Lauinger Memorial Library at Georgetown University in Washington, DC.

[17] Late in life Ward described it as "set a hundred years or more ago ... in an obviously foreign land", but that the story's situation and characters could be encountered "almost anywhere at any time".

[20] To French comics scripter Jérôme LeGlatin [fr], the "madman" in the title could be interpreted as any of a number of its characters: the laughing image adorning the drum, the subdued African, the slave trader, and even Ward himself.

[24] A reviewer for The Burlington Magazine in 1931 judged the book a failed experiment, finding the artwork uneven and the narrative hard to follow without even the chapter titles of Gods' Man.

He believes the book has strengths and weaknesses: it has stronger compositions, but the more finely engraved images are "harder to read",[17] and the death of the wife and other plot points are unclear and difficult to interpret.

By contrast, Grant Scott argues that "the novel serves as a major and largely successful attempt to push images as far as they will go in the direction of the semantic, lapidary complexity of the modernist novel” ,[30] and Jérôme LeGlatin sees Madman's Drum as Ward's first masterpiece, "[triumphing] at every fault, [succeeding] in each failure" as Ward freed himself from the restraint displayed in Gods' Man.