Gods' Man

Gods' Man appeared a week before the Wall Street Crash of 1929; it nevertheless enjoyed strong sales and remains the best-selling American wordless novel.

Its success inspired other Americans to experiment with the medium, including cartoonist Milt Gross, who parodied Gods' Man in He Done Her Wrong (1930).

[2] Ward wrote in Storyteller Without Words (1974) that too great an interval would put too much interpretational burden on the reader, while too little would make the story tedious.

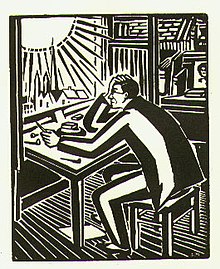

[3] The story parallels the Faust theme, and the artwork and execution show the influence of film, in particular those of German studio Ufa.

[12] In 1926, after graduating from Teachers College, Columbia University, Ward married writer May McNeer and the couple left for an extended honeymoon in Europe.

[13][14] After four months in eastern Europe, the couple settled in Leipzig in Germany, where, as a special one-year student at the National Academy of Graphic Arts and Bookmaking [de][b], Ward studied wood engraving.

[15] Nückel's only work in the genre, Destiny told of the life and death of a prostitute in a style inspired by Masereel's, but with a greater cinematic flow.

[14] The work inspired Ward to create a wordless novel of his own,[15] whose story sprang from his "youthful brooding" on the short, tragic lives of artists such as Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Keats, and Shelley; Ward's argument in the work was "that creative talent is the result of a bargain in which the chance to create is exchanged for the blind promise of an early grave".

Smith offered him a contract and told him the work would be the lead title in the company's first catalog[e] if Ward could finish it by the summer's end.

[23] In 1974, it appeared in Storyteller Without Words, a collected edition with Madman's Drum (1930) and Wild Pilgrimage (1932) prefaced with essays by Ward.

[29] The Ballet Theatre of New York considered an adaptation of Gods' Man, and a board member approached Felix R. Labunski to compose it.

[2] Abstract expressionist painter Paul Jenkins wrote Ward in 1981 of the influence the book's "energy and unprecedented originality" had on his own art.

[32] In 1973[33] Art Spiegelman created the four-page comic strip "Prisoner on the Hell Planet" about his mother's suicide,[34] executed in an Expressionist woodcut style inspired by Ward's work.

[37] Irwin Haas praised the artwork but found the storytelling uneven, and thought that only with his third wordless novel Wild Pilgrimage did Ward come to master the medium.

[38] The artwork has drawn some unintended mirth: American writer Susan Sontag included it on her "canon of Camp" in her 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'",[39] and Spiegelman admitted that the scenes of "the depiction of Our Hero idyllically skipping through the glen with the Wife and their child makes [him] snicker".