Maeshowe

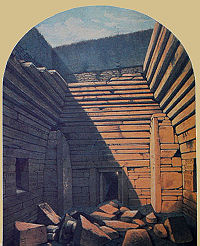

Maeshowe (or Maes Howe; Old Norse: Orkhaugr)[1] is a Neolithic chambered cairn and passage grave situated on Mainland Orkney, Scotland.

Maeshowe is a significant example of Neolithic craftsmanship and is, in the words of the archaeologist Stuart Piggott, "a superlative monument that by its originality of execution is lifted out of its class into a unique position.

The grass mound hides a complex of passages and chambers built of carefully crafted slabs of flagstone weighing up to 30 tons.

[17]: 47 A Neolithic "low road" connects Maeshowe with the magnificently preserved village of Skara Brae, passing near the Standing Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar.

Tormiston Mill Visitor Centre closed in September 2016, for various reasons, notably the small carpark and dangerous road, along with lack of wheelchair access and asbestos.

Further, the description of a passage grave states: A potential explanation for the extraordinary genius of Maeshowe engineering and the lack of human remains was described by Peter Tompkins in 1971, who compared the structure at "Maes-Howe" to the Great Pyramid[25] suggesting the site was used as an observatory, calendar, and for May Day ceremonies rather than as a tomb.

[26] He suggested the entrance was very similar to Egyptian pyramids in that it had a "54 foot observation passage aimed like a telescope at a megalithic stone [2772 feet away] to indicate the summer solstice" (p. 130) in addition to its "Watchstone" to the West that indicated the equinoxes.

[27] He cited Professor Alexander Thom, former Chair of Engineering Science at Oxford, as writing about the geometry of construction and astronomical alignment of Maeshowe in this context in 1967.

[28] Tompkins, citing Thom[citation needed] and others, described in detail how Maeshowe, Silbury Hill[29] and other ancient mounds and Neolithic megaliths across Britain served as extremely accurate observatories, calendars, and straight-line beacons for travelers, as well as how they were used ceremonially in May Day celebrations more than 4000 years ago.

John Hedges describes him as possessing "a rapacious appetite for excavation matched only by his crude techniques, lack of inspiration, and general inability to publish.

He then turned his attention to the top of the mound, broke through, and over a period of a few days, emptied the main chamber of material that had filled it completely.

He and his workmen discovered the famous runic inscriptions carved on the walls, proof that Norsemen had broken into the tomb at least six centuries earlier.

More recent fieldwork has demonstrated that the application of a computational photography technique, reflectance transformation imaging (RTI),[a] can shed light onto the nature of the inscriptions and their sequencing.

The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places.

They were approximately contemporary with the mastabas of the archaic period of Egypt (first and second dynasties), the brick temples of Sumeria, and the first cities of the Harappa culture in India, and a century or two earlier than the Golden Age of China.