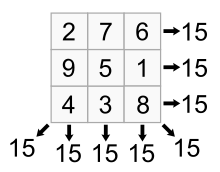

Magic square

Magic squares were made known to Europe through translation of Arabic sources as occult objects during the Renaissance, and the general theory had to be re-discovered independent of prior developments in China, India, and Middle East.

Also notable are the ancient cultures with a tradition of mathematics and numerology that did not discover the magic squares: Greeks, Babylonians, Egyptians, and Pre-Columbian Americans.

While ancient references to the pattern of even and odd numbers in the 3×3 magic square appear in the I Ching, the first unequivocal instance of this magic square appears in the chapter called Mingtang (Bright Hall) of a 1st-century book Da Dai Liji (Record of Rites by the Elder Dai), which purported to describe ancient Chinese rites of the Zhou dynasty.

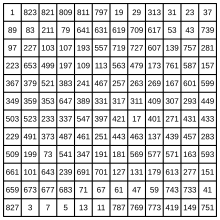

[5][7] The oldest surviving Chinese treatise that displays magic squares of order larger than 3 is Yang Hui's Xugu zheqi suanfa (Continuation of Ancient Mathematical Methods for Elucidating the Strange) written in 1275.

The high point of Chinese mathematics that deals with the magic squares seems to be contained in the work of Yang Hui; but even as a collection of older methods, this work is much more primitive, lacking general methods for constructing magic squares of any order, compared to a similar collection written around the same time by the Byzantine scholar Manuel Moschopoulos.

The first dateable instance of 3×3 magic square in India occur in a medical text Siddhayog (c. 900 CE) by Vrnda, which was prescribed to women in labor in order to have easy delivery.

[17] The oldest dateable fourth order magic square in the world is found in an encyclopaedic work written by Varahamihira around 587 CE called Brhat Samhita.

In the last section, he conceives of other figures, such as circles, rectangles, and hexagons, in which the numbers may be arranged to possess properties similar to those of magic squares.

[8] While it is known that treatises on magic squares were written in the 9th century, the earliest extant treaties date from the 10th-century: one by Abu'l-Wafa al-Buzjani (c. 998) and another by Ali b. Ahmad al-Antaki (c. 987).

[22][24][25] These early treatises were purely mathematical, and the Arabic designation for magic squares used is wafq al-a'dad, which translates as harmonious disposition of the numbers.

[22] However, much of these later texts written for occult purposes merely depict certain magic squares and mention their attributes, without describing their principle of construction, with only some authors keeping the general theory alive.

[27] The magic square of order three was described as a child-bearing charm[28][29] since its first literary appearances in the alchemical works of Jābir ibn Hayyān (fl.

The earliest occurrence of the association of seven magic squares to the virtues of the seven heavenly bodies appear in Andalusian scholar Ibn Zarkali's (known as Azarquiel in Europe) (1029–1087) Kitāb tadbīrāt al-kawākib (Book on the Influences of the Planets).

Moschopoulos was essentially unknown to the Latin Europe until the late 17th century, when Philippe de la Hire rediscovered his treatise in the Royal Library of Paris.

[32] The magic square of three was discussed in numerological manner in early 12th century by Jewish scholar Abraham ibn Ezra of Toledo, which influenced later Kabbalists.

[41][42] It is interesting to observe that Paolo Dagomari, like Pacioli after him, refers to the squares as a useful basis for inventing mathematical questions and games, and does not mention any magical use.

As said, the same point of view seems to motivate the fellow Florentine Luca Pacioli, who describes 3×3 to 9×9 squares in his work De Viribus Quantitatis by the end of 15th century.

In 1624 France, Claude Gaspard Bachet described the "diamond method" for constructing Agrippa's odd ordered squares in his book Problèmes Plaisants.

[47] By this time the earlier mysticism attached to the magic squares had completely vanished, and the subject was treated as a part of recreational mathematics.

The order four normal magic square Albrecht Dürer immortalized in his 1514 engraving Melencolia I, referred to above, is believed to be the first seen in European art.

In 1997 Lee Sallows discovered that leaving aside rotations and reflections, then every distinct parallelogram drawn on the Argand diagram defines a unique 3×3 magic square, and vice versa, a result that had never previously been noted.

This square also has a further diabolical property that any five cells in quincunx pattern formed by any odd sub-square, including wrap around, sum to the magic constant, 65.

This means that the complementary pair α and δ (or β and γ) can appear twice in a column (or a row) and still give the desired magic sum.

These continuous enumeration algorithms were discovered in 10th century by Arab scholars; and their earliest surviving exposition comes from the two treatises by al-Buzjani and al-Antaki, although they themselves were not the discoverers.

Still using Ali Skalli's non iterative method, it is possible to produce an infinity of multiplicative magic squares of complex numbers[80] belonging to

[84] In 2017, following initial ideas of William Walkington and Inder Taneja, the first linear area magic square (L-AMS) was constructed by Walter Trump.

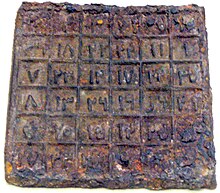

[90] The magical operations involve engraving the appropriate square on a plate made with the metal assigned to the corresponding planet,[91] as well as performing a variety of rituals.

In about 1510 Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa wrote De Occulta Philosophia, drawing on the Hermetic and magical works of Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola.

A magic square in a musical composition is not a block of numbers – it is a generating principle, to be learned and known intimately, perceived inwardly as a multi-dimensional projection into that vast (chaotic!)

Projected onto the page, a magic square is a dead, black conglomeration of digits; tune in, and one hears a powerful, orbiting dynamo of musical images, glowing with numen and lumen.