Magma

Magma (from Ancient Greek μάγμα (mágma) 'thick unguent')[1] is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed.

[2] Magma (sometimes colloquially but incorrectly referred to as lava) is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural satellites.

Mantle and crustal melts migrate upwards through the crust where they are thought to be stored in magma chambers[6] or trans-crustal crystal-rich mush zones.

Following its ascent through the crust, magma may feed a volcano and be extruded as lava, or it may solidify underground to form an intrusion,[8] such as a dike, a sill, a laccolith, a pluton, or a batholith.

[24] Unusually hot (>950 °C; >1,740 °F) rhyolite lavas, however, may flow for distances of many tens of kilometres, such as in the Snake River Plain of the northwestern United States.

Because of their lower silica content and higher eruptive temperatures, they tend to be much less viscous, with a typical viscosity of 3.5 × 106 cP (3,500 Pa⋅s) at 1,200 °C (2,190 °F).

[28] Higher iron and magnesium tends to manifest as a darker groundmass, including amphibole or pyroxene phenocrysts.

[34] Some silicic magmas have an elevated content of alkali metal oxides (sodium and potassium), particularly in regions of continental rifting, areas overlying deeply subducted plates, or at intraplate hotspots.

Carbon dioxide is much less soluble in magmas than water, and frequently separates into a distinct fluid phase even at great depth.

This explains the presence of carbon dioxide fluid inclusions in crystals formed in magmas at great depth.

These bubbles had significantly reduced the density of the magma at depth and helped drive it toward the surface in the first place.

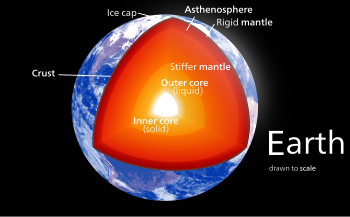

The geothermal gradient averages about 25 °C/km in the Earth's upper crust, but this varies widely by region, from a low of 5–10 °C/km within oceanic trenches and subduction zones to 30–80 °C/km along mid-ocean ridges or near mantle plumes.

The average geothermal gradient is not normally steep enough to bring rocks to their melting point anywhere in the crust or upper mantle, so magma is produced only where the geothermal gradient is unusually steep or the melting point of the rock is unusually low.

[59] Rocks may melt in response to a decrease in pressure,[60] to a change in composition (such as an addition of water),[61] to an increase in temperature,[62] or to a combination of these processes.

[63] Decompression melting creates the ocean crust at mid-ocean ridges, making it by far the most important source of magma on Earth.

Hydrous magmas with the composition of basalt or andesite are produced directly and indirectly as results of dehydration during the subduction process.

[71] With low density and viscosity, hydrous magmas are highly buoyant and will move upwards in Earth's mantle.

[73] Magmas of rock types such as nephelinite, carbonatite, and kimberlite are among those that may be generated following an influx of carbon dioxide into mantle at depths greater than about 70 km.

Temperatures can also exceed the solidus of a crustal rock in continental crust thickened by compression at a plate boundary.

Studies of electrical resistivity deduced from magnetotelluric data have detected a layer that appears to contain silicate melt and that stretches for at least 1,000 kilometers within the middle crust along the southern margin of the Tibetan Plateau.

[77] Granite and rhyolite are types of igneous rock commonly interpreted as products of the melting of continental crust because of increases in temperature.

[82] High-magnesium magmas, such as komatiite and picrite, may also be the products of a high degree of partial melting of mantle rock.

However, because the melt has usually separated from its original source rock and moved to a shallower depth, the reverse process of crystallization is not precisely identical.

However, in a series of experiments culminating in his 1915 paper, Crystallization-differentiation in silicate liquids,[91] Norman L. Bowen demonstrated that crystals of olivine and diopside that crystallized out of a cooling melt of forsterite, diopside, and silica would sink through the melt on geologically relevant time scales.

Bowen's reaction series is important for understanding the idealised sequence of fractional crystallisation of a magma.

Assimilation near the roof of a magma chamber and fractional crystallization near its base can even take place simultaneously.

Fractional crystallization models would be produced to test the hypothesis that they share a common parental magma.

After its formation, magma buoyantly rises toward the Earth's surface, due to its lower density than the source rock.

Alternatively, if the magma is erupted it forms volcanic rocks such as basalt, andesite and rhyolite (the extrusive equivalents of gabbro, diorite and granite, respectively).

The high temperatures and pressure of the magma steam were used to generate 36 MW of power, making IDDP-1 the world's first magma-enhanced geothermal system.