Magnetic domain

This means that the individual magnetic moments of the atoms are aligned with one another and they point in the same direction.

[2] He suggested that large number of atomic magnetic moments (typically 1012-1018) [citation needed] were aligned parallel.

In the original Weiss theory the mean field was proportional to the bulk magnetization M, so that

Later, the quantum theory made it possible to understand the microscopic origin of the Weiss field.

When a sample is cooled below the Curie temperature, for example, the equilibrium domain configuration simply appears.

The exchange interaction which creates the magnetization is a force which tends to align nearby dipoles so they point in the same direction.

Forcing adjacent dipoles to point in different directions requires energy.

The other energy cost to creating domains with magnetization at an angle to the "easy" direction is caused by the phenomenon called magnetostriction.

However, since the magnetic domain is "squished in" with its boundaries held rigid by the surrounding material, it cannot actually change shape.

So instead, changing the direction of the magnetization induces tiny mechanical stresses in the material, requiring more energy to create the domain.

To form these closure domains with "sideways" magnetization requires additional energy due to the aforementioned two factors.

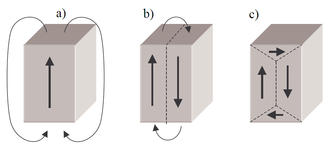

In its lowest energy state, the magnetization of neighboring domains point in different directions, confining the field lines to microscopic loops between neighboring domains within the material, so the combined fields cancel at a distance.

Therefore, a bulk piece of ferromagnetic material in its lowest energy state has little or no external magnetic field.

The contributions of the different internal energy factors described above is expressed by the free energy equation proposed by Lev Landau and Evgeny Lifshitz in 1935,[7] which forms the basis of the modern theory of magnetic domains.

A stable domain structure is a magnetization function M(x), considered as a continuous vector field, which minimizes the total energy E throughout the material.

Therefore, micromagnetics has evolved approximate methods which assume that the magnetization of dipoles in the bulk of the domain, away from the wall, all point in the same direction, and numerical solutions are only used near the domain wall, where the magnetization is changing rapidly.

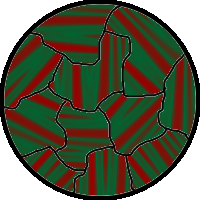

In magnetic materials, domains can be circular, square, irregular, elongated, and striped, all of which have varied sizes and dimensions.

Another technique for viewing sub-microscopic domain structures down to a scale of a few nanometers is magnetic force microscopy.

MFM is a form of atomic force microscopy that uses a magnetically coated probe tip to scan the sample surface.

[10] The technique involves placing a small quantity of ferrofluid on the surface of a ferromagnetic material.

A modified Bitter technique has been incorporated into a widely used device, the Large Area Domain Viewer, which is particularly useful in the examination of grain-oriented silicon steels.