Magnetic levitation

[3] Earnshaw's theorem proves that using only paramagnetic materials (such as ferromagnetic iron) it is impossible for a static system to stably levitate against gravity.

However, servomechanisms, the use of diamagnetic materials, superconduction, or systems involving eddy currents allow stability to be achieved.

Earnshaw's theorem proved conclusively that it is not possible to levitate stably using only static, macroscopic, paramagnetic fields.

Conductors can have a relative permeability to alternating magnetic fields of below one, so some configurations using simple AC-driven electromagnets are self stable.

When a levitation system uses negative feedback to maintain its equilibrium by damping out any oscillations that may occur, it has achieved dynamic stability.

In practice many of the levitation schemes are marginally stable and, when non-idealities of physical systems are considered, result in negative damping.

This can be accomplished in a number of ways: For successful levitation and control of all 6 axes (degrees of freedom; 3 translational and 3 rotational) a combination of permanent magnets and electromagnets or diamagnets or superconductors as well as attractive and repulsive fields can be used.

[11] Halbach arrays are also well-suited to magnetic levitation and stabilisation of gyroscopes and spindles of electric motors and generators.

[16] However, the magnetic fields required for this are very high, typically in the range of 16 teslas, and therefore create significant problems if ferromagnetic materials are nearby.

, where: Assuming ideal conditions along the z-direction of solenoid magnet: Superconductors may be considered perfect diamagnets, and completely expel magnetic fields due to the Meissner effect when the superconductivity initially forms; thus superconducting levitation can be considered a particular instance of diamagnetic levitation.

[17] Several devices using rotational stabilization (such as the popular Levitron branded levitating top toy) have been developed citing this patent.

Non-commercial devices have been created for university research laboratories, generally using magnets too powerful for safe public interaction.

A typical EML coil has reversed winding of upper and lower sections energized by a radio frequency power supply.

[24] Several research studies report the realization of different custom setups to properly obtain the desired control of microrobots.

The dimension of magnets varies between different versions, while typically in the range of 1.4[29]-2[28] mm square shape with a lower height.

The driving platform PCB was built with multiple layers of wire traces like a voice coil actuation.

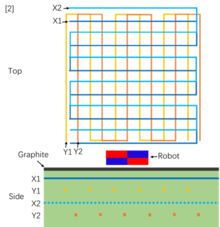

Shown in figure [1] there are four layers of wires in the PCB board which represents two sets placed perpendicular to each other that stand for X and Y direction movement.

This equation can be integrated to find the velocity of the microrobot: Introducing the relation between magnet volume, mass, and density

Diamagnetically levitated milli- and micro-robots can be controlled and moved with near-zero noise in their force, and they can be made intrinsically stable.

Diamagnetic levitation seems promising because of its accurate control, zero friction, and zero wear, but becomes less reliable at higher payloads as its max bearing pressure is in the order of 102.

Therefore, ferrofluids, with a max bearing pressure in the order of 2 x 104, have been studied to increase the amount of weight that magnetic force can pull.

This repulsion arises from diamagnets' magnetization direction being antiparallel to the external field, enabling passive levitation and facilitating advanced control strategies.

To achieve passive levitation, a diamagnetic layer, such as graphite, must be present in conjunction with a ferromagnetic material, such as neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB).

These simulations provide critical insights into the force profile experienced by the micro robot at varying heights above the magnet array.

Legends of magnetic levitation were common in ancient and medieval times, and their spread from the Roman world to the Middle East and later to India has been documented by the classical scholar Dunstan Lowe.

[37][38] The earliest known source is Pliny the Elder (first century AD), who described architectural plans for an iron statue that was to be suspended by lodestone from the vault of a temple in Alexandria.

Many subsequent reports described levitating statues, relics or other objects of symbolic importance, and versions of the legend have appeared in diverse religious traditions, including Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism.

In some cases they were interpreted as divine miracles, while in others they were described as natural phenomena falsely purported to be miraculous; one example of the latter comes from St Augustine, who refers to a magnetically suspended statue in his book The City of God (c. 410 AD).

Another common feature of these legends, according to Lowe, is an explanation of the object's disappearance, often involving its destruction by non-believers in acts of impiety.

Although the phenomenon itself is now understood to be physically impossible, as was first recognized by Samuel Earnshaw in 1842, stories of magnetic levitation have persisted to modern times, one prominent example being the legend of the suspended monument in the Konark Sun Temple in Eastern India.