Plate tectonics

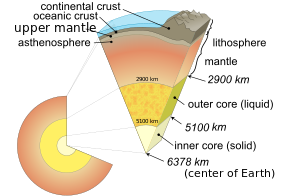

The greater density of old lithosphere relative to the underlying asthenosphere allows it to sink into the deep mantle at subduction zones, providing most of the driving force for plate movement.

[20] For much of the first quarter of the 20th century, the leading theory of the driving force behind tectonic plate motions envisaged large scale convection currents in the upper mantle, which can be transmitted through the asthenosphere.

However, despite its acceptance, it was long debated in the scientific community because the leading theory still envisaged a static Earth without moving continents up until the major breakthroughs of the early sixties.

There are essentially two main types of mechanisms that are thought to exist related to the dynamics of the mantle that influence plate motion which are primary (through the large scale convection cells) or secondary.

These ideas find their roots in the early 1930s in the works of Beloussov and van Bemmelen, which were initially opposed to plate tectonics and placed the mechanism in a fixed frame of vertical movements.

[29] Recent research, based on three-dimensional computer modelling, suggests that plate geometry is governed by a feedback between mantle convection patterns and the strength of the lithosphere.

Later studies (discussed below on this page), therefore, invoked many of the relationships recognized during this pre-plate tectonics period to support their theories (see reviews of these various mechanisms related to Earth rotation the work of van Dijk and collaborators).

The debate is still open, and a recent paper by Hofmeister et al. (2022)[42] revived the idea advocating again the interaction between the Earth's rotation and the Moon as main driving forces for the plates.

[49] Starting from the idea (also expressed by his forerunners) that the present continents once formed a single land mass (later called Pangaea), Wegener suggested that these separated and drifted apart, likening them to "icebergs" of low density sial floating on a sea of denser sima.

Confirmation of their previous contiguous nature also came from the fossil plants Glossopteris and Gangamopteris, and the therapsid or mammal-like reptile Lystrosaurus, all widely distributed over South America, Africa, Antarctica, India, and Australia.

The South African Alex du Toit put together a mass of such information in his 1937 publication Our Wandering Continents, and went further than Wegener in recognising the strong links between the Gondwana fragments.

During the late 1950s, it was successfully shown on two occasions that these data could show the validity of continental drift: by Keith Runcorn in a paper in 1956,[55] and by Warren Carey in a symposium held in March 1956.

[56] The second piece of evidence in support of continental drift came during the late 1950s and early 60s from data on the bathymetry of the deep ocean floors and the nature of the oceanic crust such as magnetic properties and, more generally, with the development of marine geology[57] which gave evidence for the association of seafloor spreading along the mid-oceanic ridges and magnetic field reversals, published between 1959 and 1963 by Heezen, Dietz, Hess, Mason, Vine & Matthews, and Morley.

However, based on abnormalities in plumb line deflection by the Andes in Peru, Pierre Bouguer had deduced that less-dense mountains must have a downward projection into the denser layer underneath.

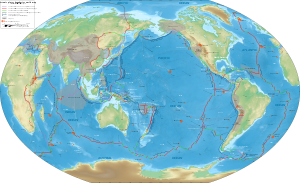

During the 20th century, improvements in and greater use of seismic instruments such as seismographs enabled scientists to learn that earthquakes tend to be concentrated in specific areas, most notably along the oceanic trenches and spreading ridges.

By the late 1920s, seismologists were beginning to identify several prominent earthquake zones parallel to the trenches that typically were inclined 40–60° from the horizontal and extended several hundred kilometers into Earth.

The study of global seismicity greatly advanced in the 1960s with the establishment of the Worldwide Standardized Seismograph Network (WWSSN)[65] to monitor the compliance of the 1963 treaty banning above-ground testing of nuclear weapons.

[67] Often, these contributions are forgotten because: In 1947, a team of scientists led by Maurice Ewing utilizing the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's research vessel Atlantis and an array of instruments, confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and found that the floor of the seabed beneath the layer of sediments consisted of basalt, not the granite which is the main constituent of continents.

In reality, this question had been solved already by numerous scientists during the 1940s and the 1950s, like Arthur Holmes, Vening-Meinesz, Coates and many others: The crust in excess disappeared along what were called the oceanic trenches, where so-called "subduction" occurred.

The question particularly intrigued Harry Hammond Hess, a Princeton University geologist and a Naval Reserve Rear Admiral, and Robert S. Dietz, a scientist with the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey who coined the term seafloor spreading.

The important step Hess made was that convection currents would be the driving force in this process, arriving at the same conclusions as Holmes had decades before with the only difference that the thinning of the ocean crust was performed using Heezen's mechanism of spreading along the ridges.

This finding, though unexpected, was not entirely surprising because it was known that basalt—the iron-rich, volcanic rock making up the ocean floor—contains a strongly magnetic mineral (magnetite) and can locally distort compass readings.

The overall pattern, defined by these alternating bands of normally and reversely polarized rock, became known as magnetic striping, and was published by Ron G. Mason and co-workers in 1961, who did not find, though, an explanation for these data in terms of sea floor spreading, like Vine, Matthews and Morley a few years later.

This process, at first denominated the "conveyer belt hypothesis" and later called seafloor spreading, operating over many millions of years continues to form new ocean floor all across the 50,000 km-long system of mid-ocean ridges.

Extensive studies were dedicated to the calibration of the normal-reversal patterns in the oceanic crust on one hand and known timescales derived from the dating of basalt layers in sedimentary sequences (magnetostratigraphy) on the other, to arrive at estimates of past spreading rates and plate reconstructions.

[90] Some authors have suggested that during at least part of the Archean period (~4-2.5 billion years ago) the mantle was between 100 and 250 °C warmer than at present, which is thought to be incompatible with modern-style plate tectonics, and that Earth may have had a stagnant lid or other kinds of regimes.

There is debatable evidence of active tectonics in the planet's distant past; however, events taking place since then (such as the plausible and generally accepted hypothesis that the Venusian lithosphere has thickened greatly over the course of several hundred million years) has made constraining the course of its geologic record difficult.

This research has led to the fairly well accepted hypothesis that Venus has undergone an essentially complete volcanic resurfacing at least once in its distant past, with the last event taking place approximately within the range of estimated surface ages.

While the mechanism of such an impressive thermal event remains a debated issue in Venusian geosciences, some scientists are advocates of processes involving plate motion to some extent.

[104] Scientists have since determined that it was created either by upwelling within the Martian mantle that thickened the crust of the Southern Highlands and formed Tharsis[105] or by a giant impact that excavated the Northern Lowlands.

Divergent: