Malagasy language

Malagasy also includes numerous Malay loanwords,[5] from the time of the early Austronesian settlement and trading between Madagascar and the Sunda Islands.

[6] After c. 1000 AD, Malagasy incorporated numerous Bantu and Arabic loanwords brought over by traders and new settlers.

Malagasy is written in the Latin script introduced by Western missionaries in the early 19th century.

Madagascar was first settled by Austronesian peoples from Maritime Southeast Asia from the Sunda Islands (Malay archipelago).

[13] As for their route, one possibility is that the Indonesian Austronesian came directly across the Indian Ocean from Java to Madagascar.

It is likely that they went through the Maldives, where evidence of old Indonesian boat design and fishing technology persists until the present.

[20] There is evidence that the predecessors of the Malagasy dialects first arrived in the southern stretch of the east coast of Madagascar.

It is also spoken by Malagasy communities on neighboring Indian Ocean islands such as Réunion, Mayotte and Mauritius.

Expatriate Malagasy communities speaking the language also exist in Europe and North America.

It is one of two official languages alongside French in the 2010 constitution put in place the Fourth Republic.

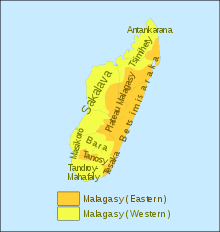

There are two principal dialects of Malagasy: Eastern (including Merina) and Western (including Sakalava), with the isogloss running down the spine of the island, the south being western, and the central plateau and much of the north (apart from the very tip) being eastern.

Sakalava lost final nasal consonants, whereas Merina added a voiceless [ə̥]: Final *t became -[tse] in the one but -[ʈʂə̥] in the other: Sakalava retains ancestral *li and *ti, whereas in Merina these become [di] (as in huditra 'skin' above) and [tsi]: However, these last changes started in Borneo before Malagasy arrived in Madagascar.

When the French established Fort-Dauphin in the 17th century, they found an Arabico-Malagasy script in use, known as Sorabe ("large writings").

[20] The first bilingual renderings of religious texts are those by Étienne de Flacourt,[27] who also published the first dictionary of the language.

[28] Radama I, the first literate representative of the Merina monarchy, though extensively versed in the Arabico-Malagasy tradition,[29] opted in 1823 for a Latin system derived by David Jones and invited the Protestant London Missionary Society to establish schools and churches.

The large number of reduced vowels, and their effect on neighbouring consonants, give Malagasy a phonological quality not unlike that of Portuguese.

The reported postalveolar trilled affricates /ʈʳ ᶯʈʳ ɖʳ ᶯɖʳ/ are sometimes simple stops, [ʈ ᶯʈ ɖ ᶯɖ], but they often have a rhotic release, [ʈɽ̊˔ ᶯʈɽ̊˔ ɖɽ˔ ᶯɖɽ˔].

[33] The Malagasy sounds are frequently transcribed [ʈʂ ᶯʈʂ ɖʐ ᶯɖʐ], and that is the convention used in this article.

In many dialects, unstressed vowels (except /e/) are devoiced, and in some cases almost completely elided; thus fanòrona is pronounced [fə̥ˈnurnə̥].

According to Penelope Howe in 2021, Central Malagasy is undergoing tonogenesis, with syllables containing voiced consonants are "fully devoiced" and acquire a low tone (/ba/ → [b̥à]), while those containing unvoiced consonants acquire a high tone (/pa/ → [pá]).

[34] Malagasy has a verb–object–subject (VOS) word order: MamakyreadsbokybooknythempianatrastudentMamaky boky ny mpianatrareads book the student"The student reads the book"Nividyboughtrononomilkhoforan'nythezazachildnythevehivavywomanNividy ronono ho an'ny zaza ny vehivavybought milk for the child the woman"The woman bought milk for the child"Within phrases, Malagasy order is typical of head-initial languages: Malagasy has prepositions rather than postpositions (ho an'ny zaza "for the child").

Whereas later works have been of lesser size, several have been updated to reflect the evolution and progress of the language, including a more modern, bilingual frequency dictionary based on a corpus of over 5 million Malagasy words.